Responding to Joseph Stiglitz on Negative Interest Rates

Link to the Wikipedia article for Joseph Stiglitz

I thought twice before I tweeted on Monday “Joe Stiglitz is making a fool of himself with his arguments against negative rates” in reaction to his April 13, 2016 Project Syndicate piece “What’s Wrong With Negative Rates?” wondering if I was being too hard on him. But then I thought to myself “I have no problem saying that I make a fool of myself with some regularity.” In particular, I often make of a fool of myself by venturing an opinion in order to see if someone can help me learn if I am wrong, and if so, why. I hope that Joe Stiglitz made a fool of himself in exactly that spirit–in which case I honor him for that.

What Joe says is complex, so it is best to proceed point by point, even if that occasions some repetition. And it helps in separating the wheat from the chaff; Joe says some things that are correct, even though his bottom line is off target–in particular his final paragraph:

Of course, even in the best of circumstances, monetary policy’s ability to restore a slumping economy to full employment may be limited. But relying on the wrong model prevents central bankers from contributing what they can – and may even make a bad situation worse.

This final paragraph is quite wrong:

- After eliminating the zero lower bound by freeing up the paper currency interest rate from its traditional value of zero, monetary policy alone has more than enough power to return an economy to the natural level of output.

- The insights from standard models should not be dismissed so quickly.

- To the extent that central bankers are making a mistake, it is not by going to negative interest rates, but by keeping the paper currency interest rate at zero, with all the attendant strains that causes.

In what follows, all block quotes that follow will be Joe Stiglitz’s words.

1. An Aggregate Demand Problem

The underlying problem – which has plagued the global economy since the crisis, but has worsened slightly – is lack of global aggregate demand.

Correct. Lack of aggregate demand is hardly the only problem of the world economy (a slower rate of technological progress than from 1995-2003 may be a bigger problem), but it is a big and pressing problem.

2. The Zero Lower Bound

Now, in response, the European Central Bank (ECB) has stepped up its stimulus, joining the Bank of Japan and a couple of other central banks in showing that the “zero lower bound” – the inability of interest rates to become negative – is a boundary only in the imagination of conventional economists.

Although the lower bound may not be at zero, a lot of the stresses and strains that are being felt from negative interest rate policy have to do with the fact that the paper currency interest rate has not yet been cut below zero to match target rates and interest rates on reserves. If the paper currency interest rates gets too far above the interest rate on reserves and the target rate, it is hard for banks to make a living on spreads in the way they are used to. In particular, it is hard for banks to lower the interest rates on checking accounts and saving accounts very far below zero without having small-scale depositors significantly raise their paper currency holdings and reduce the funds they hold in checking and savings accounts. The solution is simple: lower the paper currency interest rate, as I discuss in “If a Central Bank Cuts All of Its Interest Rates, Including the Paper Currency Interest Rate, Negative Interest Rates are a Much Fiercer Animal” and lay out in detail in two academic papers and many columns and blog posts I have collected links for in “How and Why to Eliminate the Zero Lower Bound: A Reader’s Guide.”

The so-called “zero lower bound,” should be thought of as a more complex danger of massive paper currency storage and of disintermediation away from the banking system into paper currency that begins to occur when the paper currency interest rate is kept too far above the target rate and the interest rate on reserves. This danger may or may not be well described by the phrase “the zero lower bound,” but it is not a myth. Much of what Joe says in his essay is pointing out that the danger of disintermediation is not a myth. Hence the importance of lowering the paper currency interest rate along with the target rate and the interest rate on reserves.

3. Why Negative Rates Have Not Brought Full Recovery

Joe writes

And yet, in none of the economies attempting the unorthodox experiment of negative interest rates has there been a return to growth and full employment.

He has a sentence that should have followed immediately, but is several paragraphs further down:

Clearly, the idea that large corporations precisely calculate the interest rate at which they are willing to undertake investment – and that they would be willing to undertake a large number of projects if only interest rates were lowered by another 25 basis points – is absurd.

In other words, the 30 basis point cut in interest rates that the European Central Bank has made is a tiny dosage of negative rates. The effectiveness of negative interest rates has to be judged per basis point. When unhindered by a perceived zero lower bound, it is normal for a central bank in a recessionary situation to cut interest rates by 600 to 700 basis points (that is 6 or 7 percentage points). That is the kind of dosage that can be expected to get results. And go the extent that risk premia rose more during the Financial Crisis than during a normal recession, safe rates need to go enough lower to compensate for those higher risk premia.

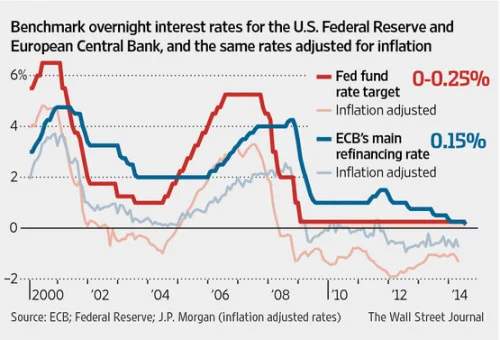

As can be seen from the graph above, the European Central Bank’s target rate was at about 4% in nominal terms at the onset of the Financial crisis. A 7 percentage point point cut would have taken the rate to -3%, which would have done a fairly good job. But a bit lower was probably appropriate given elevated risk premia. -4% in 2009 would have been an excellent policy, well within historical norms for an interest rate cut in a serious recession if one treats interest rates in the negative region on a par with interest rates in the positive region–as makes sense if one is taking the paper currency interest rate down along with other rates, so that spread between the paper currency interest rate and the target rate as small. Thinking of the norm as a 6 percentage point cut but the elevation of risk premia in this episode as 2% would have lead to the same recommendation of a -4% interest rate in 2009. But of course, after going to -4%, the European Central Bank should then have paid attention to the data about whether that was enough or not, and gone down further if need be, less if -4% was too stimulative.

Note that even without the adjustment for elevated risk premia, the rule of thumb of a 6 percentage point cut to deal with recessions leads to a real interest rate below -2% during the trough if the real interest rate starts out below 4%. For a variety of reasons detailed in Lukasz Rachel and Thomas Smith’s excellent Bank of England blog post “Drivers of long-term global interest rates – can changes in desired savings and investment explain the fall?” the real medium-run natural rate of interest has been falling over the past few decades. So a 6 percentage point cut in interest rates in a recession needs to go down to lower real interest rate than before. For example, it is not at all unreasonable to think that the real medium-run natural rate of interest rate is hovering around .5%, which means that a real interest rate of -5.5% in the trough is appropriate medicine to bring economic recovery.

Joe says correctly that -2% real interest rates haven’t done the trick:

In many economies – including Europe and the United States – real (inflation-adjusted) interest rates have been negative, sometimes as much as -2%. And yet, as real interest rates have fallen, business investment has stagnated.

Joe is also likely correct that a real interest rate of -3.5% or -4% would not be enough:

A decrease in the real interest rate – that on government bonds – to -3% or even -4% will make little or no difference.

But it is quite wrong to think that if nominal interest rate of -2%, which makes for a real interest rate of -4% at 2% inflation won’t do the trick that one should give up on negative interest rates. If one lowers the paper currency interest rate along with other rates, it is quite possible to have nominal interest rates at -4%, -5%, -6% or even -7% or lower if necessary. And that is the range standard rules of thumb suggest would be necessary–with the lower numbers in that range only necessary if there are unusual problems with the economy–which there might be.

In “Even Central Bankers Need Lessons on the Transmission Mechanism for Negative Interest Rates” I wrote: “If starting from current conditions, any country can maintain interest rates at -7% or lower for two years without overheating its economy, then I am wrong about the power of negative interest rates.” Despite all the uncertainties about what is going on with key economies in the world, I stand by that statement–with the exception of a non-market economy such as North Korea where there is no true market interest rate.

4. Will Negative Rates Make Lending Rates Increase?

Joe writes:

In some cases, the outcome has been unexpected: Some lending rates have actually increased.

The reason for raising lending rates in the wake of negative rates on reserves is presumably to increase profits for a bank that has had profits reduced by the negative interest rate on reserves. But the interest a bank earns on its lending to firms and households is enough separate from what it earns on what it lends to the central bank as reserves that if the bank can increase profits by raising its lending rates, it could probably have done that all along. The connection with negative deposit rates would then be that banks might hope governmental authorities will take pity on them, or be concerned enough about their balance sheets because of the negative rates they are paying on reserves that the governmental authorities give the banks less of a hard time about oligopolistically raising lending rates in the negative rate situation than they normally would. But this then boils down to a governmental concern about bank profits and bank balance sheets, which can be addressed in more direct and more productive ways than by allowing banks to exert more oligopoly power.

5. How to Deal with Worries about the Effects of Negative Interest Rates on Bank Balance Sheets

Joe exhibits concern about the effects of negative rates on bank balance sheets in this passage:

Negative interest rates hurt banks’ balance sheets, with the “wealth effect” on banks overwhelming the small increase in incentives to lend. Unless policymakers are careful, lending rates could increase and credit availability decline.

Since banks live on spreads, the most basic way to avoid hurting bank profits and therefore bank balance sheets is to keep spreads normal. Quantitative easing tends to squeeze key spreads and so departs from that approach. And leaving the paper currency interest rate at zero while cutting the target rate and the interest rate on reserves also departs from that approach. The way to keep things as normal as possible for banks is to lower all government-controlled interest rates in tandem. In its latest move, the European Central Bank at least lowered its lending rates along with the interest rates on reserves. That was intended to be helpful to bank profits, and it is hard to doubt that it is.

Even if the paper currency interest rate is negative, banks may have trouble explaining to small-scale, unsophisticated depositors why they need to have a negative interest rate on deposits. If banks therefore continue to give zero rates to small-scale, unsophisticated depositors, this is likely to hurt profits in a negative interest rate environment. But for the political acceptability of negative rates, it is in the interest of most central banks to support banks in continuing to give zero interest rates to small-scale, unsophisticated depositors. In “How to Handle Worries about the Effect of Negative Interest Rates on Bank Profits with Two-Tiered Interest-on-Reserves Policies,” I propose that central banks use tiers in the interest on reserves formula to effectively subsidize and incentivize banks in providing a zero interest rate to the first 1000 euros or so of average monthly balances per adult. (I discuss there how some kind of depositor identification is needed in order to avoid double-dipping.) At some cost to the seignorage that a central bank would otherwise gain from negative rates, this helps banks and shields most people (though only a small fraction of funds) from negative deposit rates.

Of course, if banks were adequately capitalized to begin with, or otherwise have robust profits (perhaps because of very strong oligopoly power, as in Sweden), there may be no need to throw money to banks to help their balance sheets, which reduces but does not eliminate the benefits of subsidizing the provision of zero interest rates to small accounts.

6. Can Negative Interest Rates Stimulate the Economy When Banks are Broken?

Joe has a passage talking generally about failed models that is a bit hard to interpret, but I think it has to do with his view that banks are central to understanding how the macroeconomy works.

It should have been apparent that most central banks’ pre-crisis models – both the formal models and the mental models that guide policymakers’ thinking – were badly wrong. None predicted the crisis; and in very few of these economies has a semblance of full employment been restored. The ECB famously raised interest rates twice in 2011, just as the euro crisis was worsening and unemployment was increasing to double-digit levels, bringing deflation ever closer.

They continued to use the old discredited models, perhaps slightly modified. In these models, the interest rate is the key policy tool, to be dialed up and down to ensure good economic performance. If a positive interest rate doesn’t suffice, then a negative interest rate should do the trick.

The evidence for that interpretation comes in this subsequent passage:

It may come as a shock to non-economists, but banks play no role in the standard economic model that monetary policymakers have used for the last couple of decades. Of course, if there were no banks, there would be no central banks, either; but cognitive dissonance has seldom shaken central bankers’ confidence in their models.

I discussed above how to address concerns about bank balance sheets. I also discussed how to deal with increased risk premia: cut the safe rate enough further to compensate for the higher risk premia–that is, to lean towards–in effect–targeting the risky rates that firms and households borrow at rather than the safe rates that a government with reasonable finances can borrow at. This works well even if the negative rates themselves have some effect on the relevant risk premia, since risk premia will not be infinite. (And indeed, the models of credit rationing to which Joe contributed with his academic work say that while a higher loan interest rate may not result in more lending because it can be associated with lower loan quality, a low enough cost of funds for the bank will reduce the amount of rationing.)

In “On the Need for Large Movements in Interest Rates to Stabilize the Economy with Monetary Policy,” I argue:

Businesses and banks sitting on idle piles of liquid assets is a telltale symptom of the zero lower bound. Breaking through the zero lower bound restores the functioning of banks. Given negative interest rates those piles of liquid assets (after perhaps earning an initial capital gain), face a low rate of return going forward if they are left in that form. So the banks have to do something. They might simply get involved in financing storage, perhaps through a wholly-owned subsidiary if they didn’t trust anyone else with those funds. And as noted above, storage of long-lived goods alone can bring recovery. But chances are the banks would begin thinking about making loans for regular forms of investment. And the subset of businesses that have their own piles of liquid assets would also begin thinking about using their own money to invest.

That is, banks look broken when their cost of funds has not been reduced enough to make the cost of funds plus an appropriate risk premium lower than the rates at which there is loan demand.

Also, while banks are important, they are far from the whole story. Note for example that when firms are sitting on large piles of safe assets, as many have been during the Great Depression, they can invest without a bank being involved at all. They don’t because the risk-adjusted return on projects looks lower to them than the zero or slightly below zero nominal rate they can earn on safe assets. Does Joe Stiglitz really believe that there is a shortage of projects that would look good compared to a safe return of -7% in nominal terms–or -9% in real terms at 2% inflation? In all likelihood there are many projects with a much better return than that, so that going as low as -7% rates would be unnecessary to get strong economic recovery.

In “Even Central Bankers Need Lessons on the Transmission Mechanism for Negative Interest Rates,” I put the importance of banks in perspective by pointing out that every type of borrower/lender relationship in which the market interest rate declines creates extra stimulus. Banks are parties to many borrower/lender relationships, but far from all. I recommend the detailed treatment in “Even Central Bankers Need Lessons on the Transmission Mechanism for Negative Interest Rates” to those who still think it is all about banks.

I don’t mean to say banks aren’t important. They are. They just aren’t the whole story. And low enough interest rates can stimulate the economy even if the channels involving banks in their canonical role as lenders to small businesses is obstructed. As I wrote in “On the Need for Large Movements in Interest Rates to Stabilize the Economy with Monetary Policy”: “At the end of the day, low enough interest rates will bring recovery one way or another. If risk premia remained high enough, recovery could come through unusual channels, but it would come.”

7. Wealth Effects

I discussed how to deal with wealth effects on banks themselves above. Joe mentions wealth effects in one other context, writing:

… older people who depend on interest income, hurt further, cut their consumption more deeply than those who benefit – rich owners of equity – increase theirs, undermining aggregate demand today.

My post “Even Central Bankers Need Lessons on the Transmission Mechanism for Negative Interest Rates” enunciates a key principle about wealth effects: because there are two parties to every borrower-lender relationship, what is a negative wealth effect to one party is a positive wealth effect to the other. And on the whole, borrowers–who tend to get a wealth effect boost from lower rates–are better spenders than lenders. So if all the wealth effects are accounted for rather than cherry-picking a wealth effect here or there, they will be in the direction of greater stimulus from lower rates. Here is the overall story about transmission mechanisms for lower rates, in the negative region as well as the positive region: In any nook or cranny of the economy where interest rates fall, whether in the positive or negative region, those lower interest rates create more aggregate demand by a substitution effect on both the borrower and lender, while other than any expansion of the economy overall, wealth effects that can be large for individual economic actors largely cancel out in the aggregate.

Regardless of how cherry-picked, it is interesting to think whether the borrow-lender relationship of senior citizens lending to big firms and their owners is an exception to the general rule that borrowers tend to be better at spending than lenders–that is that borrowers generally tend to have a higher marginal propensity to consume. It depends on whether the operating arms of the firm pay attention to lower interest rates by lowering the hurdle rate for projects. It is an important question whether firms adjust hurdle rates for investment projects when market interest rates fall, or if only the Chief Financial Officer pays attention to lower market rates (for the sake of purely financial transactions to raise the value of the firm even if the physical things the firm does are held constant).

But to address the cherry-picking, think of senior citizens who lend instead to the federal government. Lower interest rates reduce the deficit and tend to lead to more government spending fairly directly by deficit reduction rules biting less. Even though senior citizens have a high marginal propensity to consume, I think the effects of deficit numbers on government behavior make the effective marginal propensity to consume of the federal government out of a change in interest expense even higher. Those who like the idea of fiscal stimulus should be happy about this stimulus from negative interest rates–especially since the negative wealth effect is only for the relatively well-off senior citizens who are not just living on social security, but have interest income to live on on top of that.

Also, to point out another aspect of the cherry-picking (even keeping the picked cherry of “senior citizens”), think of senior citizens who are lending to companies, but hold relatively long-term bonds. If many of the bonds have roughly the same maturity as the remaining life-span of a senior citizen, the wealth effects are much reduced since the coupons are locked in. It is senior citizens who have short-term holdings that a good financial planner would warn them against who have trouble with the wealth effects from lower interest rates.

Finally, I question the idea that those near the end of their lives would have such a high consumption response to interest rates, even if they were constrained to hold only T-bills. The reason is that as the end of life approaches, the principal of the debt instruments one holds matters more and more relative to the interest. The last time I refinanced, I got a 10-year mortgage. With that short a mortgage, the need to pay off principal in such a short time means that the monthly payment was not that sensitive to the interest rate. Similarly, with, say, only 10 years left to live, the amount one can afford to take from one’s savings to spend is not that sensitive to the interest rate. One might say that uncertainty makes people act as if they had longer to live than they actually do, but that would have a big effect in reducing the marginal propensity to consume out of wealth that would tend to counterbalance any increased wealth-equivalent impact of a change in interest rates.

8. Reaching for Yield

Joe worries about the effects of lower interest rates on financial stability:

the perhaps irrational but widely documented search for yield implies that many investors will shift their portfolios toward riskier assets, exposing the economy to greater financial instability.

I owe all my readers a post with the diagram I gave my students on this, but here is its idea: lower rates boost aggregate demand a lot, reduce financial stability only a little; higher equity (capital) requirements boost financial stability a lot, reduce aggregate demand only a little. Combine the two policies: lower rates and higher equity requirements, and you get an increase in both aggregate demand and financial stability–exactly what is needed. Scale that policy up, and you can get as big an increase in both aggregate demand and a quite large increase in financial stability at the same time. These are two great policies that go well together.

Update: the May 10, 2016 post “Why Financial Stability Concerns Are Not a Reason to Shy Away from a Robust Negative Interest Rate Policy” is the promised post.

9. The Capital/Labor Ratio

Joe makes this interesting argument:

…low interest rates encourage firms to invest in more capital-intensive technologies, resulting in demand for labor falling in the longer term, even as unemployment declines in the short term.

The most basic response is that if monetary policy does its job–getting output back to the natural level–it has no further effect on long-run issues such as this. Indeed, monetary policy has no effect on the medium-run natural interest rate. So if low interest rates in the medium- to long-run are a problem, they are not the province of monetary policy. (Update: See “Mario Draghi Reminds Everyone that Central Banks Do Not Determine the Medium-Run Natural Interest Rate.”)

In this area that is not the province of monetary policy, I think there is more reason to worry about people’s ability to save for retirement in a lower interest rate environment than labor demand in a low interest rate environment. In standard models in which capital and labor are homothetic with only one type of labor, for a given technology, a higher capital/labor ratio raises medium-run labor demand. To the extent that different production methods can be thought of as all part of the same technology, the ability to switch between production methods reduces this positive effect of the capital/labor ratio on labor demand, but does not eliminate it. What is true is that in models with more than one type of labor, capital might raise the demand for some types of labor and reduce the demand for other types. It may be that the types of labor for which demand increases are much better paid than the types of labor for which demand decreases, and that the number of workers demanded goes down as demand shifts toward a few high-quality workers instead of many lower-quality workers. But the amount of this that happens as a result of interest rates is probably small compared to the amount that happens as a result of technological progress and from globalization. And to repeat, monetary policy cannot do much to either bring on or stop such trends since monetary policy has no effect on interest rates once it has done its job of getting the economy back to the natural level of output.

All of that is in the medium- to long-run. You might say “What about the short-run?” Well, the short run is the province of monetary policy, and negative interest rates are–in cases that look increasingly important–a way to get enough aggregate demand to keep labor demand at a level appropriate to any medium- to long-run situation, so that the short run is not messed up.

Note: Those interested in the share of capital income might be interested in “The Wrong Side of Cobb-Douglas: Matt Rognlie’s Smackdown of Thomas Piketty Gains Traction.”

As noted above, my bibliographic post “How and Why to Eliminate the Zero Lower Bound: A Reader’s Guide” organizes links to everything I have written about negative interest rate policy.