Insufficient Sleep Contributes to Obesity, Diabetes, Heart Disease, Cancer and Neurodegenerative Disorders—Ken Wright →

Here are some key quotations from the interview linked above, with bullets added to separate passages

… burning the candle all week and trying to “catch up on sleep” on the weekend not only doesn’t work well, but could actually worsen metabolic health in some ways.

… one easy way to recalibrate an off-kilter body clock, or circadian rhythm, is to go camping.

insufficient sleep contributes to all the major health problems, from obesity and Type 2 diabetes to heart disease, cancer and neurodegenerative disorders.

… toward a future in which, along with having their blood tested for cholesterol levels at the doctor’s office, patients might also get a test assessing whether they are natural night owls or morning larks and personalized prescriptions for how to better time their lives.

Price Stickiness Endangers Scientific Experiments Using Helium

There is a shortage of helium. But that shouldn’t be endangering high-value projects: a higher price can reduce the less important use of helium for party balloons or projects that can wait, while preserving the most essential uses of helium. But apparently there has been some reluctance to raise helium prices on the part of suppliers, resulting in rationing:

Vidoudez has spent countless hours calling or emailing just about every supplier that he could find.

“Most just either don’t answer or the ones that do answer say, ‘We don’t take new customers at the moment,’” Vidoudez said. “It’s been a real struggle.”

This is a good example of why those who raise prices when there are shortages are heroes, not the “price-gouging” villains they are sometimes made out to be. If you get a windfall because there is an unexpected shortage in what you sell, it would be great for you to give some of your windfall to charity, but keeping your price low is bad for society in such a situation.

Update, June 15, 2022: Of course, the “wealth effects” on scientific grants of fluctuations in helium prices can also be disruptive. A good answer to this, which physicists have pursued, is to have the equivalent of futures contracts for helium. Then the “wealth effects” of helium price fluctuations are zeroed out. Ideally, it is possible to take the money from the futures contract and not use the helium; that leaves the “substitution effect” (the incentive effect) of a price increase intact. And of course if the price goes down, the substitution effect is intact—one can buy more helium at the lower spot price if that is attractive.

Gradually Growing Sophistication in How Colleges are Evaluated

In “False Advertising for College is Pretty Much the Norm,” I argue:

Colleges and universities claim to do two things for their students: help them learn and help them get jobs. …

On job placement, the biggest deception by prestigious colleges and universities is to claim credit for the brainpower and work habits that students already had when they arrived. Another important deception is to obscure the difference between the job-placement accomplishments of students who graduate from technical fields such as economics, business, engineering or the life sciences, and the lesser success of students in the humanities, fields like communications or in most social sciences.

In Money’s “The Best Colleges in America, Ranked by Value,” the situation is getting a little better. A lot of Money’s focus is on providing possible students a more accurate idea of how much a college costs, which I didn’t focus on in my diatribe. But in some of the components of their evaluation described in their methodology explanation are in the direction I called for:

Major-adjusted early career earnings: (15%). Research shows that a student’s major has a significant influence on their earning potential. To account for this, we used College Scorecard program-level earnings of students who graduated in 2017 and 2018. These are the earnings of graduates from the same academic programs at the same colleges, one and two years after they earned a degree. We then calculated an average salary, weighted by the share of the bachelor’s degree completers in each major (grouped by CIP program levels). Then, we used a clustering algorithm to group colleges that have a similar mix of majors and compared the weighted average against colleges in the same group. Colleges whose weighted average was higher than that of their group scored well. This allows us to compare schools that produce graduates who go into fields with very different earnings potentials.

Value-added early career earnings (15%). We analyzed how students’ actual earnings 10 years after enrolling compared with the rate predicted of students at schools with similar student bodies.

…

Economic mobility: 10%. Think tank Third Way recently published new economic mobility data for each college, based on a college’s share of low- and moderate-income students and a college’s “Price-to-Earnings Premium” (PEP) for low-income students. The PEP measures the time it takes students to recoup their educational costs given the earnings boost they obtain by attending an institution. Low-income students were defined as those whose families make $30,000 or less. We used this as an indicator of which colleges are helping promote upward mobility. This data is new this year, and replaces an older mobility rate we had been using from Opportunity Insights.

Adjusting earnings for major and for the characteristics of students when they enter college is a step forward. I would like to have (a) seen these components emphasized more and (b) had the main table distinguish between earnings for different majors, so prospective students could see how much they sacrifice in earnings to pursue less-well-remunerated majors.

In “False Advertising for College is Pretty Much the Norm,” I also argue for direct measurement of learning:

To demonstrate that a school helps students learn, schools should have every student who takes a follow-up course take a test at the beginning of each semester on what they were supposed to have learned in the introductory course. The school can get students to take it seriously enough to get decent data — but not seriously enough to cram for it — by saying they have to pass it to graduate, but that they can always retake it in the unlikely event they don’t pass the first time. To me, it is a telling sign of how little most colleges and universities care as institutions about learning that so few have a systematic policy to measure long-run learning by low-stakes, follow-up tests at some distance in time after a course is over.

Some readers might argue that earnings are the ultimate goal, so measuring the intermediate outcome of learning is unnecessary. But I’ll bet that other unmeasured factors affect earnings to a greater degree than other unmeasured factors affect learning of the specific types of knowledge that colleges purport to teach. So measuring learning is a way to focus on an intermediate outcome likely to be to a greater extent causally due to college. And learning may be of some value to students in their lives beyond what it contributes to measured earning. For example, college graduates are healthier than those who don’t graduate from college, may make better consumer decisions and may get more enjoyment out of inexpensive entertainments such as reading books. Some colleges may do a better job at helping students learn things that will help their health, their decision-making and their enjoyment. As an even bigger deal, some colleges may do a better job at helping students choose life goals that those students will find meaningful in the future.

I describe some of my economics department’s effort to measuring learning in “Measuring Learning Outcomes from Getting an Economics Degree.” I discuss measurement of learning more in “How to Foster Transformative Innovation in Higher Education” and argue that measuring skill acquisition unlocks new, improved possibilities for higher education:

I want to make the radical claim that colleges and universities should, first and foremost, be in the business of educating students well. One implication of this radical claim is that colleges’ and universities’ performance should be measured by value added—by graduation rates and how much stronger graduating students are academically than they were at matriculation. By this standard, bringing in students who were impressive in high school raises the standards for what one should minimally expect a college’s or university’s students to look like at graduation, and colleges and universities become truly impressive if they help weak students become strong.

… The key to allowing alternative forms of higher education to flourish is to replace the current emphasis on accreditation, which tends to lock in the status quo, and instead have the government or a foundation with an interest in higher education develop high-quality assessment tools for what skills a student has at graduation. Distinct skills should be separately certified. The biggest emphasis should be on skills directly valuable in the labor market: writing, reading carefully, coding, the lesser computer and math skills needed to be a whiz with a spreadsheet, etc. But students should be able to get certified in every key skill that a college or university purports to teach. (Where what should be taught is disputed, as in the Humanities, there should be alternative certification routes, such as a certification in the use of Postmodernism and a separate certification for knowledge of what was conceived as the traditional canon 75 years ago. The nature of the assessment in each can be controlled by professors who believe in that particular school of thought.)

Having an assessment that allows a student to document a skill allows for innovation in how to get to that level of skill. …

To the extent colleges and universities claim to be teaching higher-order thinking, an assessment tool to test higher-order thinking is needed. One might object that testing higher-order thinking would be expensive, but it takes an awful lot of money to amount to all that much compared to four or more years of college tuition. And colleges and universities should be ashamed if they think we should take them seriously were they to claim that what they taught was so ineffable that it would be impossible for a student to demonstrate they had that skill in a structured test situation.

Conclusion: Outcome measurement matters. If you want to change the world for the better using your statistical or test-designing skills, figuring out how to do better outcome measurement for colleges and universities is a high leverage activity.

The Federalist Papers #55: How Big Should the House of Representatives Be?

The Federalist Papers #55 discusses the optimal size for the House of Representatives. The author (Alexander Hamilton or James Madison) argues that there is a large range of reasonable answers:

… no political problem is less susceptible of a precise solution than that which relates to the number most convenient for a representative legislature; nor is there any point on which the policy of the several States is more at variance, whether we compare their legislative assemblies directly with each other, or consider the proportions which they respectively bear to the number of their constituents.

Nevertheless, there are some concerns that could make the size of the House of Representatives too big or too small. The danger from being too big (besides the expense, which is not mentioned) is that it might act like a mob:

… the number ought at most to be kept within a certain limit, in order to avoid the confusion and intemperance of a multitude. In all very numerous assemblies, of whatever character composed, passion never fails to wrest the sceptre from reason.

Had every Athenian citizen been a Socrates, every Athenian assembly would still have been a mob.

The behavior of large groups of people is something about which we have some social science evidence (synchronized movement can help submerge the individual within the group) and some experience that tends to bear out this concern (Occupy Wall Street and Black Lives Matter have gone to extremes because they have had no centralized leadership).

But it was the dangers of a too-small House of Representatives that were more on the minds of critics of the proposed Constitution. Quoting relevant passages, here are some of the concerns:

so small a number of representatives will be an unsafe depositary of the public interests

they will not possess a proper knowledge of the local circumstances of their numerous constituents

they will be taken from that class of citizens which will sympathize least with the feelings of the mass of the people, and be most likely to aim at a permanent elevation of the few on the depression of the many

it will be more and more disproportionate, by the increase of the people, and the obstacles which will prevent a correspondent increase of the representatives

The author of the Federalist Papers #55 allows that the first concern is important:

… a certain number at least seems to be necessary… to guard against too easy a combination for improper purposes

and adds a 5th reason for a body that is not too small:

5. a certain number at least seems to be necessary to secure the benefits of free consultation and discussion

It is taken as obvious that, at least numerically, 60 or 70 is enough to go a long way toward getting most of the benefit of having more heads to think something through. Answers to the 2d, 3d and 4th concerns is deferred to a later number.

On the worry that, if small in number, the House of Representatives could easily be bribed or could easily conspire, the Federalist Papers #55 argues that the number will soon be several hundred, and that the men who would be representatives when the body is initially less than one hundred had already passed the test of not trying to take tyrannical power during the Revolutionary War and after:

The Congress which conducted us through the Revolution was a less numerous body than their successors will be; they were not chosen by, nor responsible to, their fellow citizens at large; though appointed from year to year, and recallable at pleasure, they were generally continued for three years, and prior to the ratification of the federal articles, for a still longer term.

They held their consultations always under the veil of secrecy; they had the sole transaction of our affairs with foreign nations; through the whole course of the war they had the fate of their country more in their hands than it is to be hoped will ever be the case with our future representatives; and from the greatness of the prize at stake, and the eagerness of the party which lost it, it may well be supposed that the use of other means than force would not have been scrupled. Yet we know by happy experience that the public trust was not betrayed; nor has the purity of our public councils in this particular ever suffered, even from the whispers of calumny.

There is a strange discussion of whether the President and Senate would be rich enough to bribe the House of Representatives, motivated by the President and the Senate being a new element in the picture. But the key argument is the one above—that the likely members of the House of Representatives when it would be small were men who had been shown trustworthy by events.

How have things turned out? Now, the United States has 435 members of the House of Representatives. There are definitely concerns about those representatives being bought by moneyed interests, but I don’t see why those moneyed interests couldn’t work their co-opting magic on 4000 representatives. And I don’t notice a degeneration into acting like a mob from having so many as 435.

The question of how large a deliberative body should be is one that comes up all around the world, in many contexts. To mention just one, how many voting members should a monetary policy committee have?

Below is the full text of the Federalist Papers #55:

FEDERALIST NO. 55

The Total Number of the House of Representatives

From the New York Packet

Friday, February 15, 1788.

Author: Alexander Hamilton or James Madison

To the People of the State of New York:

THE number of which the House of Representatives is to consist, forms another and a very interesting point of view, under which this branch of the federal legislature may be contemplated.

Scarce any article, indeed, in the whole Constitution seems to be rendered more worthy of attention, by the weight of character and the apparent force of argument with which it has been assailed.

The charges exhibited against it are, first, that so small a number of representatives will be an unsafe depositary of the public interests; secondly, that they will not possess a proper knowledge of the local circumstances of their numerous constituents; thirdly, that they will be taken from that class of citizens which will sympathize least with the feelings of the mass of the people, and be most likely to aim at a permanent elevation of the few on the depression of the many; fourthly, that defective as the number will be in the first instance, it will be more and more disproportionate, by the increase of the people, and the obstacles which will prevent a correspondent increase of the representatives. In general it may be remarked on this subject, that no political problem is less susceptible of a precise solution than that which relates to the number most convenient for a representative legislature; nor is there any point on which the policy of the several States is more at variance, whether we compare their legislative assemblies directly with each other, or consider the proportions which they respectively bear to the number of their constituents. Passing over the difference between the smallest and largest States, as Delaware, whose most numerous branch consists of twenty-one representatives, and Massachusetts, where it amounts to between three and four hundred, a very considerable difference is observable among States nearly equal in population. The number of representatives in Pennsylvania is not more than one fifth of that in the State last mentioned. New York, whose population is to that of South Carolina as six to five, has little more than one third of the number of representatives. As great a disparity prevails between the States of Georgia and Delaware or Rhode Island. In Pennsylvania, the representatives do not bear a greater proportion to their constituents than of one for every four or five thousand. In Rhode Island, they bear a proportion of at least one for every thousand. And according to the constitution of Georgia, the proportion may be carried to one to every ten electors; and must unavoidably far exceed the proportion in any of the other States. Another general remark to be made is, that the ratio between the representatives and the people ought not to be the same where the latter are very numerous as where they are very few. Were the representatives in Virginia to be regulated by the standard in Rhode Island, they would, at this time, amount to between four and five hundred; and twenty or thirty years hence, to a thousand. On the other hand, the ratio of Pennsylvania, if applied to the State of Delaware, would reduce the representative assembly of the latter to seven or eight members. Nothing can be more fallacious than to found our political calculations on arithmetical principles. Sixty or seventy men may be more properly trusted with a given degree of power than six or seven. But it does not follow that six or seven hundred would be proportionably a better depositary. And if we carry on the supposition to six or seven thousand, the whole reasoning ought to be reversed. The truth is, that in all cases a certain number at least seems to be necessary to secure the benefits of free consultation and discussion, and to guard against too easy a combination for improper purposes; as, on the other hand, the number ought at most to be kept within a certain limit, in order to avoid the confusion and intemperance of a multitude. In all very numerous assemblies, of whatever character composed, passion never fails to wrest the sceptre from reason.

Had every Athenian citizen been a Socrates, every Athenian assembly would still have been a mob.

It is necessary also to recollect here the observations which were applied to the case of biennial elections. For the same reason that the limited powers of the Congress, and the control of the State legislatures, justify less frequent elections than the public safely might otherwise require, the members of the Congress need be less numerous than if they possessed the whole power of legislation, and were under no other than the ordinary restraints of other legislative bodies. With these general ideas in our mind, let us weigh the objections which have been stated against the number of members proposed for the House of Representatives. It is said, in the first place, that so small a number cannot be safely trusted with so much power. The number of which this branch of the legislature is to consist, at the outset of the government, will be sixty five. Within three years a census is to be taken, when the number may be augmented to one for every thirty thousand inhabitants; and within every successive period of ten years the census is to be renewed, and augmentations may continue to be made under the above limitation. It will not be thought an extravagant conjecture that the first census will, at the rate of one for every thirty thousand, raise the number of representatives to at least one hundred. Estimating the negroes in the proportion of three fifths, it can scarcely be doubted that the population of the United States will by that time, if it does not already, amount to three millions. At the expiration of twenty-five years, according to the computed rate of increase, the number of representatives will amount to two hundred, and of fifty years, to four hundred. This is a number which, I presume, will put an end to all fears arising from the smallness of the body. I take for granted here what I shall, in answering the fourth objection, hereafter show, that the number of representatives will be augmented from time to time in the manner provided by the Constitution. On a contrary supposition, I should admit the objection to have very great weight indeed. The true question to be decided then is, whether the smallness of the number, as a temporary regulation, be dangerous to the public liberty? Whether sixty-five members for a few years, and a hundred or two hundred for a few more, be a safe depositary for a limited and well-guarded power of legislating for the United States? I must own that I could not give a negative answer to this question, without first obliterating every impression which I have received with regard to the present genius of the people of America, the spirit which actuates the State legislatures, and the principles which are incorporated with the political character of every class of citizens I am unable to conceive that the people of America, in their present temper, or under any circumstances which can speedily happen, will choose, and every second year repeat the choice of, sixty-five or a hundred men who would be disposed to form and pursue a scheme of tyranny or treachery. I am unable to conceive that the State legislatures, which must feel so many motives to watch, and which possess so many means of counteracting, the federal legislature, would fail either to detect or to defeat a conspiracy of the latter against the liberties of their common constituents. I am equally unable to conceive that there are at this time, or can be in any short time, in the United States, any sixty-five or a hundred men capable of recommending themselves to the choice of the people at large, who would either desire or dare, within the short space of two years, to betray the solemn trust committed to them. What change of circumstances, time, and a fuller population of our country may produce, requires a prophetic spirit to declare, which makes no part of my pretensions. But judging from the circumstances now before us, and from the probable state of them within a moderate period of time, I must pronounce that the liberties of America cannot be unsafe in the number of hands proposed by the federal Constitution. From what quarter can the danger proceed? Are we afraid of foreign gold? If foreign gold could so easily corrupt our federal rulers and enable them to ensnare and betray their constituents, how has it happened that we are at this time a free and independent nation? The Congress which conducted us through the Revolution was a less numerous body than their successors will be; they were not chosen by, nor responsible to, their fellow citizens at large; though appointed from year to year, and recallable at pleasure, they were generally continued for three years, and prior to the ratification of the federal articles, for a still longer term.

They held their consultations always under the veil of secrecy; they had the sole transaction of our affairs with foreign nations; through the whole course of the war they had the fate of their country more in their hands than it is to be hoped will ever be the case with our future representatives; and from the greatness of the prize at stake, and the eagerness of the party which lost it, it may well be supposed that the use of other means than force would not have been scrupled. Yet we know by happy experience that the public trust was not betrayed; nor has the purity of our public councils in this particular ever suffered, even from the whispers of calumny. Is the danger apprehended from the other branches of the federal government?

But where are the means to be found by the President, or the Senate, or both? Their emoluments of office, it is to be presumed, will not, and without a previous corruption of the House of Representatives cannot, more than suffice for very different purposes; their private fortunes, as they must all be American citizens, cannot possibly be sources of danger. The only means, then, which they can possess, will be in the dispensation of appointments. Is it here that suspicion rests her charge? Sometimes we are told that this fund of corruption is to be exhausted by the President in subduing the virtue of the Senate. Now, the fidelity of the other House is to be the victim. The improbability of such a mercenary and perfidious combination of the several members of government, standing on as different foundations as republican principles will well admit, and at the same time accountable to the society over which they are placed, ought alone to quiet this apprehension. But, fortunately, the Constitution has provided a still further safeguard. The members of the Congress are rendered ineligible to any civil offices that may be created, or of which the emoluments may be increased, during the term of their election.

No offices therefore can be dealt out to the existing members but such as may become vacant by ordinary casualties: and to suppose that these would be sufficient to purchase the guardians of the people, selected by the people themselves, is to renounce every rule by which events ought to be calculated, and to substitute an indiscriminate and unbounded jealousy, with which all reasoning must be vain. The sincere friends of liberty, who give themselves up to the extravagancies of this passion, are not aware of the injury they do their own cause. As there is a degree of depravity in mankind which requires a certain degree of circumspection and distrust, so there are other qualities in human nature which justify a certain portion of esteem and confidence. Republican government presupposes the existence of these qualities in a higher degree than any other form. Were the pictures which have been drawn by the political jealousy of some among us faithful likenesses of the human character, the inference would be, that there is not sufficient virtue among men for self-government; and that nothing less than the chains of despotism can restrain them from destroying and devouring one another.

PUBLIUS.

Links to my other posts on The Federalist Papers so far:

The Federalist Papers #1: Alexander Hamilton's Plea for Reasoned Debate

The Federalist Papers #3: United, the 13 States are Less Likely to Stumble into War

The Federalist Papers #4 B: National Defense Will Be Stronger if the States are United

The Federalist Papers #5: Unless United, the States Will Be at Each Others' Throats

The Federalist Papers #6 A: Alexander Hamilton on the Many Human Motives for War

The Federalist Papers #11 A: United, the States Can Get a Better Trade Deal—Alexander Hamilton

The Federalist Papers #12: Union Makes it Much Easier to Get Tariff Revenue—Alexander Hamilton

The Federalist Papers #13: Alexander Hamilton on Increasing Returns to Scale in National Government

The Federalist Papers #14: A Republic Can Be Geographically Large—James Madison

The Federalist Papers #21 A: Constitutions Need to be Enforced—Alexander Hamilton

The Federalist Papers #24: The United States Need a Standing Army—Alexander Hamilton

The Federalist Papers #27: People Will Get Used to the Federal Government—Alexander Hamilton

The Federalist Papers #30: A Robust Power of Taxation is Needed to Make a Nation Powerful

The Federalist Papers #35 A: Alexander Hamilton as an Economist

The Federalist Papers #35 B: Alexander Hamilton on Who Can Represent Whom

The Federalist Papers #36: Alexander Hamilton on Regressive Taxation

The Federalist Papers #39: James Madison Downplays How Radical the Proposed Constitution Is

The Federalist Papers #41: James Madison on Tradeoffs—You Can't Have Everything You Want

The Federalist Papers #42: Every Power of the Federal Government Must Be Justified—James Madison

The Federalist Papers #44: Constitutional Limitations on the Powers of the States—James Madison

The Federalist Papers #45: James Madison Predicts a Small Federal Government

The Federalist Papers #48: Legislatures, Too, Can Become Tyrannical—James Madison

The Federalist Papers #49: Constitutional Conventions Should Be Few and Far Between

The Federalist Papers #50: Periodic Commissions to Judge Constitutionality Won't Work

The Federalist Papers #51 A: Checks and Balance, or ‘Who Guards the Guardians?'

Is Student Debt Forgiveness Fair?

Khaleda Rahman asked me for my views on cancelling existing student debt. Influenced by Richard Shinder’s Wall Street Journal op-ed shown below, I said we should make student debt dischargeable in bankruptcy.

Here is what I wrote to Khaleda in full (he used all but the last paragraph and the links):

Most Americans would view blanket student loan forgiveness as unfair to those who sacrificed to pay off their loans. And the vast majority of college students come from the upper half of the income distribution. We already have a system for loan forgiveness for those who are in dire financial trouble: it is called bankruptcy court. We should make student loans eligible to be discharged or modified in bankruptcy on the same basis as other loans. As it is now, they can't be discharged in bankruptcy.

Part of the problem students have in paying off loans is not the loans themselves, or even the high cost of college more generally, but that often students aren't getting a good education, or aren't given a true picture of their financial prospects after different majors. Colleges and universities need to have their feet held to the fire to do collect data and do honest reporting about the quality of their education and the financial prospects of students who follow different tracks. I write about this in my Bloomberg piece "False Advertising for College is Pretty Much the Norm.”

On the high cost of college, disruptive innovation that can dramatically reduce the cost of a college education already has a foot in the door. We just need to welcome it in. I write about that in my Quartz column “The Coming Transformation of Education: Degrees Won’t Matter Anymore, Skills Will.”

A Flexiblog

As I said in the 10th anniversary post for my blog, “Everything is Changing.” I have been realizing that one of the things I love most is to be able to do tasks and projects in whatever order feels right to me at the time. Having to do things in order of urgency is sometimes necessary, but feels like a cost to me. So I’m going to try an experiment of blogging with less of a weekly schedule to my posts. I plan to write as I feel inspired to write, aiming to continue to write at a good pace overall.

In some ways, this is a return to how I did my blog at the very beginning. Then I had no particular pattern to my posts. They came out whenever I had an idea. (Of course, then I was so excited by beginning to blog that I couldn’t sleep!)

There is a Golden Mean between being too flexible and being too rigid. (See “The Golden Mean as Concavity of Objective Functions.) I think I have been too focused on avoiding the harm from being too flexible (thinking of it as being undisciplined) and not focused enough on the harm from being too rigid. But I’ll try not to overcorrect.

Everything is Changing

Today is the 10th anniversary of this blog, "Confessions of a Supply-Side Liberal." My first post, "What is a Supply-Side Liberal?" appeared on May 28, 2012. I have written an anniversary post every year since then:

I don’t say lightly that I feel more than ever in my adult life that the world is changing. The pandemic, besides its direct stresses, has made us all look at work differently. Large-scale war has returned to Europe. Political polarization and associated bad behavior is worse than it has been since the 1960s.

More parochially, the audience for blogs seems to be changing. I feel I am serving a different readership than I was a few years ago, as many are drawn off toward following the news of the other changes I mentioned above. I can’t predict where things will go in the future.

In my personal life, everything seems different in 2022. New Year’s day found me and my family temporary refugees from a wildfire that destroyed about 10% of the houses in my town of Superior, Colorado and the neighboring city of Louisville, Colorado. (See “New Year's Gratitude on the Occasion of the Marshall Fire.”) Soon after that I began a semester in which I put a concerted effort into creating a new course and improving an existing course. (See “Ethics, Happiness and Choice—Miles's Economics 4060,” “Intermediate Macroeconomics—Miles's Economics 3080.”) It felt more like I was changing than simply what I was teaching. On May 15, our youngest, Jordan, married Caroline. That, too, has far-reaching ramifications us as a family as well as for them as a couple. (Our daughter Diana married Erik in 2017. Jordan’s marriage to Caroline means both of our children are now married.)

To handle everything going on (my research continued at full speed), for the first time in a long time I missed doing some blog posts in my usual 3-times-a-week schedule (not counting link posts). But as I look back over the year’s blog posts using the “Archive” button up above I am amazed at how well I did manage to keep up the pace on my blog.

For the past decade, blogging has been a major part of my life. It gives meaning to every week as I put down in words what I have been learning and thinking and try to influence in some small way the path our civilization is taking.

A decade from now, I plan to retire. I think I can do a lot in that time, personally, academically and on this blog. And I have big plans for my retirement after that, beginning with writing an autobiography.

I look forward to seeing where the world will go in the next ten years. I am an optimist. Event sometimes thrust us into the underworld, but we learn things there and with a little luck and a lot of fortitude, we can come back stronger and more true to our deepest values. May we all strive toward a better world ten years from now than the one we see around us now. I’ll meet you there.

Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Insomnia Can Prevent Major Depression

Why do we care about causality? The primary reason is that we are looking for interventions that can make things better. Some causal results give only one part of the puzzle of designing an intervention to make things better, while other causal results directly recommend an intervention once combined with a reasonable judgment about what constitutes “better.”

The result in “Prevention of Incident and Recurrent Major Depression in Older Adults With Insomnia” by Michael R. Irwin, Carmen Carrillo, Nina Sadeghi, Martin F. Bjurstrom, Elizabeth C. Breen, and Richard Olmstead that “Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Insomnia” (CBT-I) applied to adults 60 years or older who have insomnia, but don’t initially qualify as having major depression both reduces insomnia and reduces the incidence of major depression. This is a very useful thing to know.

It is tempting to interpret this result as strong evidence that insomnia causes an increased incidence of major depression. It is quite plausible that is true, since many experiments show that extreme sleep deprivation (or extreme deprivation of just REM—dreaming—sleep) quickly causes people to go crazy. But underlying subclinical depression could easily disrupt sleep, so there is a real possibility of reverse causality. And as a statistical instrument, CBT-I does not satisfy the exclusion restriction: Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) in general is known to have a powerful effect in reducing depression even in people who don’t have insomnia. So the CBT elements in CBT-I are likely to have a direct effect in reducing depression that doesn’t all work through reducing insomnia.

What about fact that those whose insomnia lessened were especially likely to have a reduction in incidence of major depression? I am thinking of this result:

Those in the CBT-I group with sustained remission of insomnia disorder had an 82.6% decreased likelihood of depression (hazard ratio, 0.17; 95%, CI 0.04-0.73; P = .02) compared with those in the SET group without sustained remission of insomnia disorder.

That can be explained simply by lessened insomnia being a sign that the CBT principles “took” for that individual. That is, CBT is going to work better for some people than others, if only because after being taught CBT principles, some people will really use those principles in their lives and others won’t. If CBT “takes” for an individual, it can have benefits in multiple areas.

Should we care whether reduction in insomnia is the pathway by which CBT-I reduces the incidence of depression? Not if CBT-I is, and would stay, the only effective treatment for insomnia. But when there is another effective treatment for insomnia, it matters. Whether that other treatment for insomnia will reduce the incidence of depression depends on the extent to which the pathway by which CBT-I reduce depression is through lessening insomnia. The best way to find that out is to do a similar study with other effective treatments for insomnia. If enough different effective treatments for insomnia also reduce the incidence of depression, that raises confidence that the next effective treatment for insomnia will also reduce the incidence of depression, which is the most important practical thing we would mean by claiming that insomnia causes a higher incidence of depression.

Statistically, many different effective treatments for insomnia reducing the incidence of depression would make it more likely that at least one of those treatments approximately satisfied the exclusion restriction by not having a big direct effect on incidence of depression. Note how that would depend on how different the “different effective treatments for insomnia” are. For example, in the extreme, if they were all minor variations on CBT-I, then they don’t lend much additional evidentiary weight to the claim that insomnia causes a higher incidence of depression.

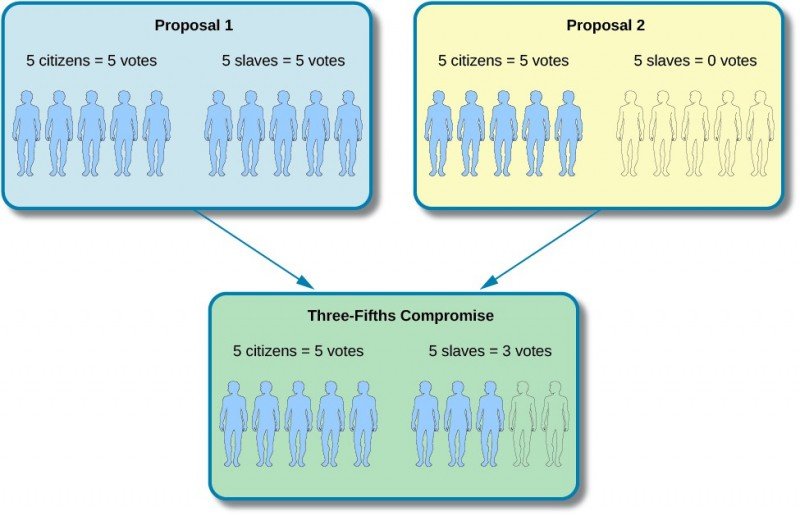

The Federalist Papers #54: Defending the Indefensible—How Attempting to Justify the 3/5 Rule for Slaves Digs the Hole Deeper

The Federalist Papers #54 provides some evidence for those who want to argue that—to an important but not total extent—the United States of America was founded on slavery. And what the Federalist Papers #54 says about slavery is only part of its horror. Below, let me lay out some of the passages that are rightly shocking to modern sensibilities, separated passages by added bullets. On slavery:

All this is admitted, it will perhaps be said; but does it follow, from an admission of numbers for the measure of representation, or of slaves combined with free citizens as a ratio of taxation, that slaves ought to be included in the numerical rule of representation? Slaves are considered as property, not as persons. They ought therefore to be comprehended in estimates of taxation which are founded on property, and to be excluded from representation which is regulated by a census of persons. This is the objection, as I understand it, stated in its full force.

… representation relates more immediately to persons, and taxation more immediately to property, and we join in the application of this distinction to the case of our slaves.

But we must deny the fact, that slaves are considered merely as property, and in no respect whatever as persons. The true state of the case is, that they partake of both these qualities: being considered by our laws, in some respects, as persons, and in other respects as property.

In being compelled to labor, not for himself, but for a master; in being vendible by one master to another master; and in being subject at all times to be restrained in his liberty and chastised in his body, by the capricious will of another, the slave may appear to be degraded from the human rank, and classed with those irrational animals which fall under the legal denomination of property. In being protected, on the other hand, in his life and in his limbs, against the violence of all others, even the master of his labor and his liberty; and in being punishable himself for all violence committed against others, the slave is no less evidently regarded by the law as a member of the society, not as a part of the irrational creation; as a moral person, not as a mere article of property. The federal Constitution, therefore, decides with great propriety on the case of our slaves, when it views them in the mixed character of persons and of property. This is in fact their true character.

Could it be reasonably expected, that the Southern States would concur in a system, which considered their slaves in some degree as men, when burdens were to be imposed, but refused to consider them in the same light, when advantages were to be conferred?

Let the case of the slaves be considered, as it is in truth, a peculiar one. Let the compromising expedient of the Constitution be mutually adopted, which regards them as inhabitants, but as debased by servitude below the equal level of free inhabitants, which regards the SLAVE as divested of two fifths of the MAN.

Such is the reasoning which an advocate for the Southern interests might employ on this subject; and although it may appear to be a little strained in some points, yet, on the whole, I must confess that it fully reconciles me to the scale of representation which the convention have established.

Saying that wealth or “property” is a legitimate basis of political power:

Government is instituted no less for protection of the property, than of the persons, of individuals. The one as well as the other, therefore, may be considered as represented by those who are charged with the government. Upon this principle it is, that in several of the States, and particularly in the State of New York, one branch of the government is intended more especially to be the guardian of property, and is accordingly elected by that part of the society which is most interested in this object of government.

It is a fundamental principle of the proposed Constitution, that as the aggregate number of representatives allotted to the several States is to be determined by a federal rule, founded on the aggregate number of inhabitants, so the right of choosing this allotted number in each State is to be exercised by such part of the inhabitants as the State itself may designate. The qualifications on which the right of suffrage depend are not, perhaps, the same in any two States. In some of the States the difference is very material. In every State, a certain proportion of inhabitants are deprived of this right by the constitution of the State, who will be included in the census by which the federal Constitution apportions the representatives.

Nor will the representatives of the larger and richer States possess any other advantage in the federal legislature, over the representatives of other States, than what may result from their superior number alone. As far, therefore, as their superior wealth and weight may justly entitle them to any advantage, it ought to be secured to them by a superior share of representation.

Not every idea in the Federalist Papers #54 is bad. This bit—logically separable from the horrifying bits—one can agree with:

In one respect, the establishment of a common measure for representation and taxation will have a very salutary effect. As the accuracy of the census to be obtained by the Congress will necessarily depend, in a considerable degree on the disposition, if not on the co-operation, of the States, it is of great importance that the States should feel as little bias as possible, to swell or to reduce the amount of their numbers. Were their share of representation alone to be governed by this rule, they would have an interest in exaggerating their inhabitants. Were the rule to decide their share of taxation alone, a contrary temptation would prevail. By extending the rule to both objects, the States will have opposite interests, which will control and balance each other, and produce the requisite impartiality.

Below is the full text of the Federalist Papers #54, to show that I have not misrepresented the thrust of this number, which is quite willing to accommodate slavery for the sake of having states that are into slavery in a big way assent to union with the other states. The author of this number (Alexander Hamilton or James Madison) is sometimes putting an argument of another imagined interlocutor, but everything I quote above about slavery is treated by the author as a reasonable argument with no hint of strong disagreement. The author actually distances himself most from anti-slavery attitudes—as you can see from this bit:

Might not some surprise also be expressed, that those who reproach the Southern States with the barbarous policy of considering as property a part of their human brethren …

FEDERALIST NO. 54

The Apportionment of Members Among the States

From the New York Packet

Tuesday, February 12, 1788.

Author: Alexander Hamilton or James Madison

To the People of the State of New York:

THE next view which I shall take of the House of Representatives relates to the appointment of its members to the several States which is to be determined by the same rule with that of direct taxes. It is not contended that the number of people in each State ought not to be the standard for regulating the proportion of those who are to represent the people of each State. The establishment of the same rule for the appointment of taxes, will probably be as little contested; though the rule itself in this case, is by no means founded on the same principle. In the former case, the rule is understood to refer to the personal rights of the people, with which it has a natural and universal connection.

In the latter, it has reference to the proportion of wealth, of which it is in no case a precise measure, and in ordinary cases a very unfit one. But notwithstanding the imperfection of the rule as applied to the relative wealth and contributions of the States, it is evidently the least objectionable among the practicable rules, and had too recently obtained the general sanction of America, not to have found a ready preference with the convention. All this is admitted, it will perhaps be said; but does it follow, from an admission of numbers for the measure of representation, or of slaves combined with free citizens as a ratio of taxation, that slaves ought to be included in the numerical rule of representation? Slaves are considered as property, not as persons. They ought therefore to be comprehended in estimates of taxation which are founded on property, and to be excluded from representation which is regulated by a census of persons. This is the objection, as I understand it, stated in its full force. I shall be equally candid in stating the reasoning which may be offered on the opposite side. "We subscribe to the doctrine," might one of our Southern brethren observe, "that representation relates more immediately to persons, and taxation more immediately to property, and we join in the application of this distinction to the case of our slaves. But we must deny the fact, that slaves are considered merely as property, and in no respect whatever as persons. The true state of the case is, that they partake of both these qualities: being considered by our laws, in some respects, as persons, and in other respects as property. In being compelled to labor, not for himself, but for a master; in being vendible by one master to another master; and in being subject at all times to be restrained in his liberty and chastised in his body, by the capricious will of another, the slave may appear to be degraded from the human rank, and classed with those irrational animals which fall under the legal denomination of property. In being protected, on the other hand, in his life and in his limbs, against the violence of all others, even the master of his labor and his liberty; and in being punishable himself for all violence committed against others, the slave is no less evidently regarded by the law as a member of the society, not as a part of the irrational creation; as a moral person, not as a mere article of property. The federal Constitution, therefore, decides with great propriety on the case of our slaves, when it views them in the mixed character of persons and of property. This is in fact their true character. It is the character bestowed on them by the laws under which they live; and it will not be denied, that these are the proper criterion; because it is only under the pretext that the laws have transformed the negroes into subjects of property, that a place is disputed them in the computation of numbers; and it is admitted, that if the laws were to restore the rights which have been taken away, the negroes could no longer be refused an equal share of representation with the other inhabitants. "This question may be placed in another light. It is agreed on all sides, that numbers are the best scale of wealth and taxation, as they are the only proper scale of representation. Would the convention have been impartial or consistent, if they had rejected the slaves from the list of inhabitants, when the shares of representation were to be calculated, and inserted them on the lists when the tariff of contributions was to be adjusted? Could it be reasonably expected, that the Southern States would concur in a system, which considered their slaves in some degree as men, when burdens were to be imposed, but refused to consider them in the same light, when advantages were to be conferred? Might not some surprise also be expressed, that those who reproach the Southern States with the barbarous policy of considering as property a part of their human brethren, should themselves contend, that the government to which all the States are to be parties, ought to consider this unfortunate race more completely in the unnatural light of property, than the very laws of which they complain? "It may be replied, perhaps, that slaves are not included in the estimate of representatives in any of the States possessing them. They neither vote themselves nor increase the votes of their masters. Upon what principle, then, ought they to be taken into the federal estimate of representation? In rejecting them altogether, the Constitution would, in this respect, have followed the very laws which have been appealed to as the proper guide. "This objection is repelled by a single observation. It is a fundamental principle of the proposed Constitution, that as the aggregate number of representatives allotted to the several States is to be determined by a federal rule, founded on the aggregate number of inhabitants, so the right of choosing this allotted number in each State is to be exercised by such part of the inhabitants as the State itself may designate. The qualifications on which the right of suffrage depend are not, perhaps, the same in any two States. In some of the States the difference is very material. In every State, a certain proportion of inhabitants are deprived of this right by the constitution of the State, who will be included in the census by which the federal Constitution apportions the representatives.

In this point of view the Southern States might retort the complaint, by insisting that the principle laid down by the convention required that no regard should be had to the policy of particular States towards their own inhabitants; and consequently, that the slaves, as inhabitants, should have been admitted into the census according to their full number, in like manner with other inhabitants, who, by the policy of other States, are not admitted to all the rights of citizens. A rigorous adherence, however, to this principle, is waived by those who would be gainers by it. All that they ask is that equal moderation be shown on the other side. Let the case of the slaves be considered, as it is in truth, a peculiar one. Let the compromising expedient of the Constitution be mutually adopted, which regards them as inhabitants, but as debased by servitude below the equal level of free inhabitants, which regards the SLAVE as divested of two fifths of the MAN. "After all, may not another ground be taken on which this article of the Constitution will admit of a still more ready defense? We have hitherto proceeded on the idea that representation related to persons only, and not at all to property. But is it a just idea?

Government is instituted no less for protection of the property, than of the persons, of individuals. The one as well as the other, therefore, may be considered as represented by those who are charged with the government. Upon this principle it is, that in several of the States, and particularly in the State of New York, one branch of the government is intended more especially to be the guardian of property, and is accordingly elected by that part of the society which is most interested in this object of government. In the federal Constitution, this policy does not prevail. The rights of property are committed into the same hands with the personal rights. Some attention ought, therefore, to be paid to property in the choice of those hands. "For another reason, the votes allowed in the federal legislature to the people of each State, ought to bear some proportion to the comparative wealth of the States. States have not, like individuals, an influence over each other, arising from superior advantages of fortune. If the law allows an opulent citizen but a single vote in the choice of his representative, the respect and consequence which he derives from his fortunate situation very frequently guide the votes of others to the objects of his choice; and through this imperceptible channel the rights of property are conveyed into the public representation. A State possesses no such influence over other States. It is not probable that the richest State in the Confederacy will ever influence the choice of a single representative in any other State. Nor will the representatives of the larger and richer States possess any other advantage in the federal legislature, over the representatives of other States, than what may result from their superior number alone. As far, therefore, as their superior wealth and weight may justly entitle them to any advantage, it ought to be secured to them by a superior share of representation. The new Constitution is, in this respect, materially different from the existing Confederation, as well as from that of the United Netherlands, and other similar confederacies. In each of the latter, the efficacy of the federal resolutions depends on the subsequent and voluntary resolutions of the states composing the union. Hence the states, though possessing an equal vote in the public councils, have an unequal influence, corresponding with the unequal importance of these subsequent and voluntary resolutions. Under the proposed Constitution, the federal acts will take effect without the necessary intervention of the individual States. They will depend merely on the majority of votes in the federal legislature, and consequently each vote, whether proceeding from a larger or smaller State, or a State more or less wealthy or powerful, will have an equal weight and efficacy: in the same manner as the votes individually given in a State legislature, by the representatives of unequal counties or other districts, have each a precise equality of value and effect; or if there be any difference in the case, it proceeds from the difference in the personal character of the individual representative, rather than from any regard to the extent of the district from which he comes. "Such is the reasoning which an advocate for the Southern interests might employ on this subject; and although it may appear to be a little strained in some points, yet, on the whole, I must confess that it fully reconciles me to the scale of representation which the convention have established. In one respect, the establishment of a common measure for representation and taxation will have a very salutary effect. As the accuracy of the census to be obtained by the Congress will necessarily depend, in a considerable degree on the disposition, if not on the co-operation, of the States, it is of great importance that the States should feel as little bias as possible, to swell or to reduce the amount of their numbers. Were their share of representation alone to be governed by this rule, they would have an interest in exaggerating their inhabitants. Were the rule to decide their share of taxation alone, a contrary temptation would prevail. By extending the rule to both objects, the States will have opposite interests, which will control and balance each other, and produce the requisite impartiality.

PUBLIUS.

Links to my other posts on The Federalist Papers so far:

The Federalist Papers #1: Alexander Hamilton's Plea for Reasoned Debate

The Federalist Papers #3: United, the 13 States are Less Likely to Stumble into War

The Federalist Papers #4 B: National Defense Will Be Stronger if the States are United

The Federalist Papers #5: Unless United, the States Will Be at Each Others' Throats

The Federalist Papers #6 A: Alexander Hamilton on the Many Human Motives for War

The Federalist Papers #11 A: United, the States Can Get a Better Trade Deal—Alexander Hamilton

The Federalist Papers #12: Union Makes it Much Easier to Get Tariff Revenue—Alexander Hamilton

The Federalist Papers #13: Alexander Hamilton on Increasing Returns to Scale in National Government

The Federalist Papers #14: A Republic Can Be Geographically Large—James Madison

The Federalist Papers #21 A: Constitutions Need to be Enforced—Alexander Hamilton

The Federalist Papers #24: The United States Need a Standing Army—Alexander Hamilton

The Federalist Papers #27: People Will Get Used to the Federal Government—Alexander Hamilton

The Federalist Papers #30: A Robust Power of Taxation is Needed to Make a Nation Powerful

The Federalist Papers #35 A: Alexander Hamilton as an Economist

The Federalist Papers #35 B: Alexander Hamilton on Who Can Represent Whom

The Federalist Papers #36: Alexander Hamilton on Regressive Taxation

The Federalist Papers #39: James Madison Downplays How Radical the Proposed Constitution Is

The Federalist Papers #41: James Madison on Tradeoffs—You Can't Have Everything You Want

The Federalist Papers #42: Every Power of the Federal Government Must Be Justified—James Madison

The Federalist Papers #44: Constitutional Limitations on the Powers of the States—James Madison

The Federalist Papers #45: James Madison Predicts a Small Federal Government

The Federalist Papers #48: Legislatures, Too, Can Become Tyrannical—James Madison

The Federalist Papers #49: Constitutional Conventions Should Be Few and Far Between

The Federalist Papers #50: Periodic Commissions to Judge Constitutionality Won't Work

The Federalist Papers #51 A: Checks and Balance, or ‘Who Guards the Guardians?'

How to Get Abundant Affordable Housing

The way to have abundant affordable housing is to have abundant housing. That means making it easy to add residential units. I want to propose a simple, if radical policy that can guarantee abundant affordable housing: state or federal laws requiring mandatory permitting of trailer parks that meet a few basic standards.

There is little worry that trailer parks will spring up in a long-lasting way in totally inappropriate places, because any place land is worth too much, a trailer park operator can’t earn a profit. On the other hand, a trailer park gives a developer a nice threat point to persuade a neighborhood to allow more appropriate (and profitable) high-density housing.

Where land is cheaper—perhaps because of noise, or simply by being further out from the city center, a trailer park might make a lot of sense.

As “Do Trailer Parks and Mobile Homes Have a Future As Affordable Housing?” suggests, there is also no reason a trailer park can’t stay a trailer park but go upscale. The legal definition would be that it would have to be the locational home to manufactured housing—at least in the sense that large pieces were made in a factory. This would give an extra boost to home manufacturing, which is desperately needed. As I discuss in “Why Housing is So Expensive,” construction has shown almost no productivity growth by the usual measures. I suspect a lot of that is because most homes don’t have large pieces made in factories. It is hard to improve production if it doesn’t have some degree of centralization and standardization—or at least modularity. The bigger the percentage of homes that have large manufactured pieces, the faster total factor productivity in housing production will improve.

Note that with a state or federal law requiring mandatory permitting of trailer parks that meet a few basic standards you can get affordable housing in most places without subsidies. It is market rate affordable housing—which should be considered the Holy Grail, while subsidized affordable housing is typically just tokenism. I’d like to suggest one place to put the budgetary savings from not subsidizing housing: instead, subsidize convenient, frequent bus service to any sufficiently large concentration of trailers. This helps make sure that the affordable trailer-park housing will work for people. The residents have to be able to get to their jobs, after all—and those with low income often own unreliable cars or no car. (Note that trailer parks have full-scale house rentals as well as people who own the house and only pay plot rent and home-owner’s association fees.)

Also, nearby current residents shouldn’t have to suffer from an increase in crime when a trailer park is created next door. And those in the trailer parks themselves shouldn’t have to suffer with high crime rates, whether many felonies or many small misdemeanors. If this is a genuine danger, we need to be brutally honest about it—and if a genuine danger, it is a legitimate concern. Thus, in addition to subsidizing good bus service to new trailer parks, I suggest state and federal subsidies for extra police to police the new trailer parks and surrounding areas.

Let me give you a challenge: when you hear someone talking about affordable housing without offering a radical scheme that moves at least 10% toward what I am saying, you can know they aren’t serious about affordable housing beyond tokenism. Let’s get real about affordable housing. It is a huge part of the typical individual’s or families budget. So the poor get much less poor when housing gets cheaper. And the rich or middle class whose property values suffer some because the scarcity value is less—or because now they can’t have as much residential segregation can afford the hit.

By the way, people often talk about “systemic racism” without pointing to what it is actually made of. Barriers to residential construction are a big part of structural racism by perpetuating residential segregation that helps the rich and middle class to not care about the poor because they are out of sight, out of mind, and deprives talented children from poor families of mentors they desperately need. (If the poor living near the rich and sending their kids to the local schools makes the rich hate the poor more, rather than caring about them more, then we have worse problems.)