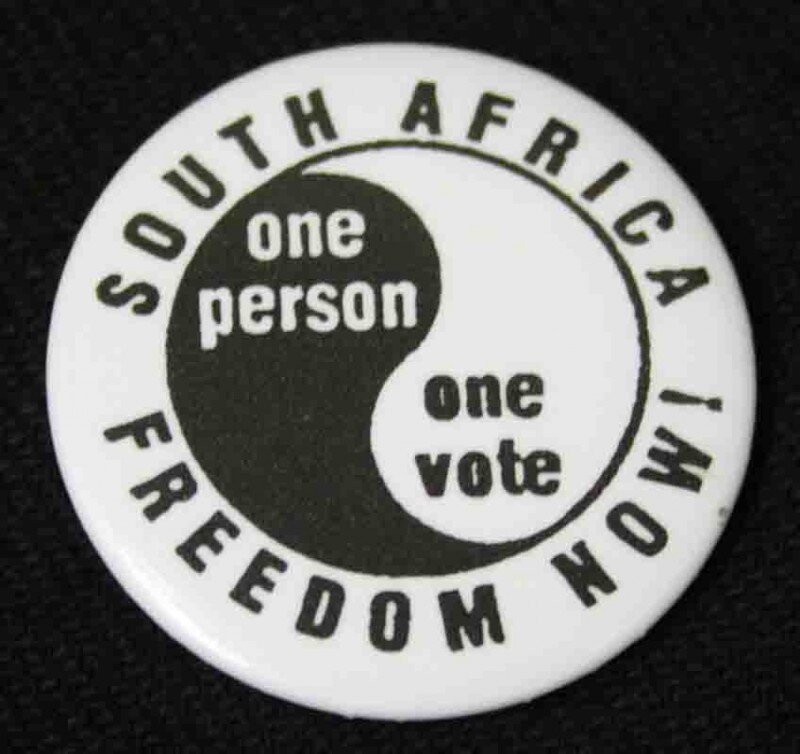

The Federalist Papers #22 B: Supermajority Rules Aren't an Adequate Fix for Departures from One-Person One-Vote—Alexander Hamilton

How to make the wishes of each person count equally in a social choice problem is a very difficult problem. But sometimes things are skewed far enough in a certain direction that it is clear the opposite direction leads to greater equality in public decision-making. One way to tell might be to think of the hypothetical experiment asking the individuals in two groups in a society whether they would be willing to exchange the political rights and influence they have for the political rights and influence of the other group. But if two groups are unequal in numbers, then one must specify whether it is the political rights and influence per person in each group or the aggregate political rights and influence of each group.

When political rights and influence per person are unequal between two groups, some might claim that is OK if most decisions must be made by consensus or by large supermajorities. In the Federalist Papers #22, Alexander begs to differ. He argues that the power to veto a decision can easily be just as important as the power to get a decision through a legislature. Nations are beset by shocks that require responses if great harm is to be avoided. If a small minority can veto a response it is difficult to make the decision necessary to avoid the harm.

Moreover, Alexander Hamilton argues that if a small minority can veto a measure, it is easier to bribe enough legislators (or offer them other inducements) for corruption to prevent action. This is true even when it is a foreign power that wants to prevent action.

On bribery and other corrupt inducements to national leaders, Alexander Hamilton makes this interesting point:

An hereditary monarch, though often disposed to sacrifice his subjects to his ambition, has so great a personal interest in the government and in the external glory of the nation, that it is not easy for a foreign power to give him an equivalent for what he would sacrifice by treachery to the state.

There is a broader principle here: if a cohesive group has the power to govern by both pushing through legislation they want and preventing legislation they don’t want, this power is likely valuable enough that it will be hard for a foreign power to bribe them. Two circumstances go away from this case. First, if a group is not cohesive, an individual might be bought off. Second, if a small minority can veto legislation, or otherwise has outsized power in some respects, but not others, then it might be possible to buy off most of that small minority, not just individuals.

(On whether a monarch can be bribed to give foreigners a lot of power, an exception to the principle Alexander Hamilton claims is that a monarch might willingly sign a document giving foreigners power over the monarch’s country, thinking to not deliver on the promise of power to foreigners. In this, the monarch might misjudge how easy it is not to deliver on that promise.)

I have the full text below of Alexander Hamiltons arguments in these regards in the Federalist Papers #22. (I moved a footnote into square brackets within the main text at one point.)

The right of equal suffrage among the States is another exceptionable part of the Confederation. Every idea of proportion and every rule of fair representation conspire to condemn a principle, which gives to Rhode Island an equal weight in the scale of power with Massachusetts, or Connecticut, or New York; and to Deleware an equal voice in the national deliberations with Pennsylvania, or Virginia, or North Carolina. Its operation contradicts the fundamental maxim of republican government, which requires that the sense of the majority should prevail. Sophistry may reply, that sovereigns are equal, and that a majority of the votes of the States will be a majority of confederated America. But this kind of logical legerdemain will never counteract the plain suggestions of justice and common-sense. It may happen that this majority of States is a small minority of the people of America [New Hampshire, Rhode Island, New Jersey, Delaware, Georgia, South Carolina, and Maryland are a majority of the whole number of the States, but they do not contain one third of the people.]; and two thirds of the people of America could not long be persuaded, upon the credit of artificial distinctions and syllogistic subtleties, to submit their interests to the management and disposal of one third. The larger States would after a while revolt from the idea of receiving the law from the smaller. To acquiesce in such a privation of their due importance in the political scale, would be not merely to be insensible to the love of power, but even to sacrifice the desire of equality. It is neither rational to expect the first, nor just to require the last. The smaller States, considering how peculiarly their safety and welfare depend on union, ought readily to renounce a pretension which, if not relinquished, would prove fatal to its duration.

It may be objected to this, that not seven but nine States, or two thirds of the whole number, must consent to the most important resolutions; and it may be thence inferred that nine States would always comprehend a majority of the Union. But this does not obviate the impropriety of an equal vote between States of the most unequal dimensions and populousness; nor is the inference accurate in point of fact; for we can enumerate nine States which contain less than a majority of the people 4; and it is constitutionally possible that these nine may give the vote. Besides, there are matters of considerable moment determinable by a bare majority; and there are others, concerning which doubts have been entertained, which, if interpreted in favor of the sufficiency of a vote of seven States, would extend its operation to interests of the first magnitude. In addition to this, it is to be observed that there is a probability of an increase in the number of States, and no provision for a proportional augmentation of the ratio of votes.

But this is not all: what at first sight may seem a remedy, is, in reality, a poison. To give a minority a negative upon the majority (which is always the case where more than a majority is requisite to a decision), is, in its tendency, to subject the sense of the greater number to that of the lesser. Congress, from the nonattendance of a few States, have been frequently in the situation of a Polish diet, where a single VOTE has been sufficient to put a stop to all their movements. A sixtieth part of the Union, which is about the proportion of Delaware and Rhode Island, has several times been able to oppose an entire bar to its operations. This is one of those refinements which, in practice, has an effect the reverse of what is expected from it in theory. The necessity of unanimity in public bodies, or of something approaching towards it, has been founded upon a supposition that it would contribute to security. But its real operation is to embarrass the administration, to destroy the energy of the government, and to substitute the pleasure, caprice, or artifices of an insignificant, turbulent, or corrupt junto, to the regular deliberations and decisions of a respectable majority. In those emergencies of a nation, in which the goodness or badness, the weakness or strength of its government, is of the greatest importance, there is commonly a necessity for action. The public business must, in some way or other, go forward. If a pertinacious minority can control the opinion of a majority, respecting the best mode of conducting it, the majority, in order that something may be done, must conform to the views of the minority; and thus the sense of the smaller number will overrule that of the greater, and give a tone to the national proceedings. Hence, tedious delays; continual negotiation and intrigue; contemptible compromises of the public good. And yet, in such a system, it is even happy when such compromises can take place: for upon some occasions things will not admit of accommodation; and then the measures of government must be injuriously suspended, or fatally defeated. It is often, by the impracticability of obtaining the concurrence of the necessary number of votes, kept in a state of inaction. Its situation must always savor of weakness, sometimes border upon anarchy.

It is not difficult to discover, that a principle of this kind gives greater scope to foreign corruption, as well as to domestic faction, than that which permits the sense of the majority to decide; though the contrary of this has been presumed. The mistake has proceeded from not attending with due care to the mischiefs that may be occasioned by obstructing the progress of government at certain critical seasons. When the concurrence of a large number is required by the Constitution to the doing of any national act, we are apt to rest satisfied that all is safe, because nothing improper will be likely TO BE DONE, but we forget how much good may be prevented, and how much ill may be produced, by the power of hindering the doing what may be necessary, and of keeping affairs in the same unfavorable posture in which they may happen to stand at particular periods.

Suppose, for instance, we were engaged in a war, in conjunction with one foreign nation, against another. Suppose the necessity of our situation demanded peace, and the interest or ambition of our ally led him to seek the prosecution of the war, with views that might justify us in making separate terms. In such a state of things, this ally of ours would evidently find it much easier, by his bribes and intrigues, to tie up the hands of government from making peace, where two thirds of all the votes were requisite to that object, than where a simple majority would suffice. In the first case, he would have to corrupt a smaller number; in the last, a greater number. Upon the same principle, it would be much easier for a foreign power with which we were at war to perplex our councils and embarrass our exertions. And, in a commercial view, we may be subjected to similar inconveniences. A nation, with which we might have a treaty of commerce, could with much greater facility prevent our forming a connection with her competitor in trade, though such a connection should be ever so beneficial to ourselves.

Evils of this description ought not to be regarded as imaginary. One of the weak sides of republics, among their numerous advantages, is that they afford too easy an inlet to foreign corruption. An hereditary monarch, though often disposed to sacrifice his subjects to his ambition, has so great a personal interest in the government and in the external glory of the nation, that it is not easy for a foreign power to give him an equivalent for what he would sacrifice by treachery to the state. The world has accordingly been witness to few examples of this species of royal prostitution, though there have been abundant specimens of every other kind.

In republics, persons elevated from the mass of the community, by the suffrages of their fellow-citizens, to stations of great pre-eminence and power, may find compensations for betraying their trust, which, to any but minds animated and guided by superior virtue, may appear to exceed the proportion of interest they have in the common stock, and to overbalance the obligations of duty. Hence it is that history furnishes us with so many mortifying examples of the prevalency of foreign corruption in republican governments. How much this contributed to the ruin of the ancient commonwealths has been already delineated. It is well known that the deputies of the United Provinces have, in various instances, been purchased by the emissaries of the neighboring kingdoms. The Earl of Chesterfield (if my memory serves me right), in a letter to his court, intimates that his success in an important negotiation must depend on his obtaining a major's commission for one of those deputies. And in Sweden the parties were alternately bought by France and England in so barefaced and notorious a manner that it excited universal disgust in the nation, and was a principal cause that the most limited monarch in Europe, in a single day, without tumult, violence, or opposition, became one of the most absolute and uncontrolled.

Here are links to my other posts on The Federalist Papers so far:

The Federalist Papers #1: Alexander Hamilton's Plea for Reasoned Debate

The Federalist Papers #3: United, the 13 States are Less Likely to Stumble into War

The Federalist Papers #4 B: National Defense Will Be Stronger if the States are United

The Federalist Papers #5: Unless United, the States Will Be at Each Others' Throats

The Federalist Papers #6 A: Alexander Hamilton on the Many Human Motives for War

The Federalist Papers #11 A: United, the States Can Get a Better Trade Deal—Alexander Hamilton

The Federalist Papers #12: Union Makes it Much Easier to Get Tariff Revenue—Alexander Hamilton

The Federalist Papers #13: Alexander Hamilton on Increasing Returns to Scale in National Government

The Federalist Papers #14: A Republic Can Be Geographically Large—James Madison

The Federalist Papers #21 A: Constitutions Need to be Enforced—Alexander Hamilton

An Optical Illusion: Nativity Scene or Two T-Rex's Fighting over a Table Saw?

I learned about this optical illusion from Andrew Sargent on Facebook

Forgive Yourself

Tomorrow is the traditional date to celebrate the birth of a man who went around telling quite a few people that their sins were forgiven. I wouldn’t be surprised if some of those to whom he told that still couldn’t forgive themselves for things they had done. It can be remarkably hard to forgive yourself for your mistakes and badnesses.

Many of us believe that it would be dangerous to forgive ourselves for our past mistakes and badnesses. But I think there is a difference between

taking responsibility for what you have done and trying to make things right and

beating yourself up about what you have done in the past.

Energy spent on beating yourself up and perhaps on feebly (or strongly) defending yourself from your own attacks is energy you aren’t spending on doing better and trying to repair the damage you have done in the past. It is an empirical matter whether beating yourself up is more helpful than discernment of what you have done wrong minus an emphasis on blame. There is little evidence to show that the very painful strategy of beating yourself up works any better than “blameless discernment” (a phrase I take from Shirzad Chamine, author of Positive Intelligence.

I like the quotation at the top of this post: “Forgiveness is giving up all hope of having had a better past.” (More than one famous person has said something like this.) We can’t change the past. We can only change what we are doing to ourselves now using bits and pieces of what we remember from our past and what is in our heads about the past more generally. Is it really helping you or the world to make yourself miserable using pointed shards from your past?

Unless you want to make what I consider the bad bet that beating yourself up is really helping you, forgiving yourself (while resolving to do better) is a good option to consider. The funny thing about forgiving yourself is that it looks more like stopping something you are doing than like doing something. Just cut the power to your attacks on yourself, and you will probably feel better and do better.

Don’t Miss These Other Posts Related to Positive Mental Health and Maintaining One’s Moral Compass:

Co-Active Coaching as a Tool for Maximizing Utility—Getting Where You Want in Life

How Economists Can Enhance Their Scientific Creativity, Engagement and Impact

Recognizing Opportunity: The Case of the Golden Raspberries—Taryn Laakso

Taryn Laakso: Battery Charge Trending to 0% — Time to Recharge

Savannah Taylor: Lessons of the Labyrinth and Tapping Into Your Inner Wisdom

A Goldbug Notices 'Breaking Through the Zero Lower Bound' and 'Enabling Deep Negative Rates to Fight Recessions: A Guide'

It is a good sign when one’s proposals are noticed, even if by someone who opposes them. Much of the video above is the standard set of ideas that sells gold and silver. In particular, in the video, Lynette Zang makes a prediction of very high inflation in the future that I think is quite unlikely. As far as modest inflation goes, Lynette neglects to note that moderate inflation tends to raise nominal wage growth. Another thing to note is that the erosion of principal that Lynette so laments as a consequence of possible future negative interest rates is the other side of debt relief for debtors—something the Bible has a different system for, but talks about as a good thing.

The welfare of debtors is important. It would be foolish to focus only on the unpleasant consequences of low interest rates for lenders and ignore the pleasant consequences for debtors. If we don’t say that “The Fed should never raise rates high to restrain inflation” because that would hurt debtors, we shouldn’t say that “The Fed should never cut rates below zero to restrain unemployment” because that would hurt lenders.

If you want to read Ruchir Agarwal’s and my papers “Breaking Through the Zero Lower Bound” and “Enabling Deep Negative Rates to Fight Recessions: A Guide,” take a look at my bilbiographic post “How and Why to Eliminate the Zero Lower Bound: A Reader’s Guide” which has those links and much, much more, including links to recent news about negative interest rates in a section that is down a ways.

On one point, I am in agreement with Lynette: I think the government should be producing gold and silver coins of defined weight that people could use as currency in a post-apocalyptic scenario. On that, see “Is Electronic Money the Mark of the Beast?” It is important however, that these gold and silver coins not be used as a unit of account or unit of price stickiness in our current non-apocalyptic or pre-apocalyptic situation, since that would mess up monetary policy quite badly, as the gold standard did for so many years in the bad old days.

Beware: Monk Fruit Nonsugar Sweetener Raises Insulin

It is easy to find boosterish articles about monk fruit sweetener online like the article shown at the bottom of this post. By I worry that anything that raises insulin levels too much could lower blood sugar enough to induce hunger. That is the view I take in “Which Nonsugar Sweeteners are OK? An Insulin-Index Perspective.” From that perspective, the evidence in the abstract shown above is worrisome. It is from the paper “Insulin secretion stimulating effects of mogroside V and fruit extract of luo han kuo (Siraitia grosvenori Swingle) fruit extract.” Swingle fruit and luo han kuo are other names for monk fruit.

The article “Insulin secretion stimulating effects of mogroside V and fruit extract of luo han kuo (Siraitia grosvenori Swingle) fruit extract” tries to bill stimulation of insulin secretion as a good thing. I don’t think that is right. Extra insulin secretion is troublesome for many reasons. See:

Another thing to worry about with sweeteners labeled as being monk fruit is that, since monk fruit extract is such a powerful sweetener, the monk fruit extract is typically diluted with other stuff—other stuff that might itself be unhealthy. Check the label to see all the ingredients.

Sweetness itself can also be a concern, though not one that stops me from using carefully chosen nonsugar sweeteners. On that, read “Which Nonsugar Sweeteners are OK? An Insulin-Index Perspective.”

Unfortunately, I don’t know how to get my hands on the full paper “Insulin secretion stimulating effects of mogroside V and fruit extract of luo han kuo (Siraitia grosvenori Swingle) fruit extract,” so I don’t know how strong the insulin-raising effect of monk fruit is if you really get monk fruit extract by itself without other worrisome stuff. It may be that because of its strong sweetness, the quantity of pure monk fruit sweetener needed for sweetening is so small that the effect on insulin would also be small. So I don’t know for sure that monk fruit extract is unhealthy. But the fact that it raises insulin is not a good sign.

For annotated links to other posts on diet and health, see:

Contrasted Faults Through All Their Manners Reign

By modern standards, Oliver Goldsmith’s 18th century poem “The Traveler—Or, a Prospect of Society” is political incorrect four times over: it is not gender neutral; it has at least one sentence that seems racist, it includes a noncondemning mention of slave-holding as a sign of wealth; and it offends national pride in its treatment of various nations. Nevertheless, it has some profound passages. Let me repurpose the following passage as a criticism of our discipline of economics:

Though poor, luxurious; though submissive, vain,

Though grave, yet trifling; zealous, yet untrue;

The first contrast, “Though poor, luxurious” fits least well. But it can apply to many economists—or indeed to any workaholic—if one thinks of “poor” as referring to a life that is not full and rich in nonfinancial ways, while “luxurious” refers to what one has bought.

The second contrast, “though submissive, vain” strikes a more powerful chord. Many economists are are vain about the how many papers they have published in which journals, but submissive to implicit, sometimes arbitrary, rules about what topics one should pursue, what methods one should use, and what things one should say in a paper. They have made themselves unreflective cogs in a machine that sometimes does the right thing and sometimes goes awry.

The third contrast “Though grave, yet trifling” is apt for the seriousness with which many economists approve of and attack dimensions of research that are orthogonal to how much potential the research has for improving the human condition, providing deeper insight into how the world works, or enabling other economists to do their work better.

Being grave in this sense is often connected to the zeal of the fourth contrast: “zealous, yet untrue.” For me, “zealous” points to those who are taught dogmas that they internalize and try to enforce on the rest of the discipline throughout the rest of their careers. “Untrue” points to any willingness to misrepresent one’s results for the sake of either one’s career advancement or to advance an ideology or dogma one adheres to.

All papers should be thought of as teaching documents, and teaching often requires some oversimplification before all the complications are added. But there are ways of doing this that show that one cares about the truth and ways of doing this that show how little one cares about truth.

Here’s to less poverty, less luxuriousness, less submissiveness, less vanity, less of being grave, less of trifling, less zeal and less untruth!

Don’t Miss These Other Posts Related to Positive Mental Health and Maintaining One’s Moral Compass:

Co-Active Coaching as a Tool for Maximizing Utility—Getting Where You Want in Life

How Economists Can Enhance Their Scientific Creativity, Engagement and Impact

Recognizing Opportunity: The Case of the Golden Raspberries—Taryn Laakso

Taryn Laakso: Battery Charge Trending to 0% — Time to Recharge

Savannah Taylor: Lessons of the Labyrinth and Tapping Into Your Inner Wisdom

James Wells: The Discovery of the Higgs Boson Opens Up Other Puzzles in Particle Physics

This SMHiggs_Fermilab.jpg figure comes from Fermilab communications. It depicts all the elementary particles, with the Higgs boson in the middle in the midst of its own generated "mist" (background non-zero field value)that gives mass to other other elementary particles.

This gammagamma_CMS.png is a picture taken from here: https://cms.cern/news/world-without-higgs

It is a Higgs boson decay into two photons, where the photons are the dashed yellow and green lines coming out of the center, which is where the Higgs was created and decayed. (It's point of creation is extremely close to where it decays because the Higgs boson lifetime is so tiny.)

I am delighted to be able to share a guest post by my friend James Wells, a Physics Professor at the Leinweber Center for Theoretical Physics at the University of Michigan, who lists his interests as

Physics beyond the Standard Model

Higgs boson properties and interactions

Particle physics in early universe cosmology

Effective field theories; Quantum field theory

Foundations and history of physics

I asked James what physicists had learned from the discovery of the Higgs boson. Below the line is his answer to that question and more:

The Higgs boson is said to have been discovered in 2012 at the Large Hadron Collider in Geneva, Switzerland. However, the curious thing about the Higgs boson is that many people did not believe it could exist as an elementary particle until it was apparently found. Even more curious, many people still are not convinced that it exists.

We are not talking about a conspiracy on the level of fake moon landing staged in a warehouse studio in Des Moines. The issue is one of determining the “true nature” of a discovery. The particle found in Geneva walks like a duck, quacks like a duck, but it might not be a duck. In fact, many researchers hold that it cannot be a duck.

Why a Higgs boson?

Let’s first discuss why nature needs a Higgs boson at all, which at the same time will reveal its vulnerabilities. The Higgs boson was postulated in the 1960s by Peter Higgs and it was later understood to be an excellent candidate for the explanation of how all elementary particles can obtain mass. Let’s define what we mean by Higgs boson:

Higgs boson: the Higgs boson is a spin-less elementary particle, which has, unlike any other elementary particle, a non-zero field value that spreads across the entire universe and gives mass to every massive elementary particle that we know about, and completes the “story of mass” in elementary particle physics.

It’s difficult to understand what is meant by “non-zero field value” but for our purposes think of it analogously as a mist everywhere that all elementary particles feel, and by feeling the mist they obtain mass. The photon does not feel the mist at all, and so it is massless. The top quark feels the mist the strongest and is therefore the heaviest, about 185 times heavier than a hydrogen atom.

One might ask, “Why can’t the other elementary particles just have mass without the Higgs boson? An astronaut has mass even if you take it out of the earth’s gravitational field!” Well, the problem is that as we understood better the nature of electrons, and photons, and quarks, which are the constituent elementary particles of protons and neutrons, we had a rather serious conundrum. Our understanding of quantum field theories told us that masses for elementary particles were incompatible with the fundamental symmetries that we had derived from observations, most notably the symmetry that governs the so-called “weak decays” of heavy nuclei (“weak symmetry”).

These “weak decays” happen when one nucleus decays to another and ejects an electron and neutrino in the process, for example. We see them in the laboratory: Cobalt-60 decays to Nickel-60 plus an electron and neutrino. We can’t ignore that. But our beautiful quantum field theory that described that so well had no way of allowing the elementary particles to have mass, which was a major stumbling block to progress in physics for years. The Higgs boson and its all-pervasive mist solved the problem.

They found the Higgs boson, right?

Now fast forward to 2012, and the announcement that the Higgs boson had been discovered at CERN. I was a staff physicist in the Theory Department at CERN and had the good fortune to be in the auditorium for the discovery announcement. What an event it was. What an achievement of the human intellect. Much celebration. People crying with joy. Reporters swarming. TV cameras in every hallway it seemed. The Director General Heueur said, “I think we got it!” meaning they finally collared this elusive particle. They saw it by measuring a small excess of two photons and four leptons (electrons and muons are both in the category of “leptons”) over normal backgrounds being produced in the collisions of protons at very high energies. It was predicted we would find it that way. They spent decades developing the detectors to make exactly that discovery. It worked. Its mass was found to be equal to approximately 134 hydrogen atoms.

The question is, however, exactly what did they find at CERN? You must keep in mind that many physicists were not expecting the Higgs boson to be there at all. The esteemed Nobel Laureate Martinus Veltman said in 1997 that “by the time you get there [when the LHC runs] you will find something else…. I don’t believe the Higgs system … as it is advertised at this point … I really don’t believe that” [1]. He was certainly not alone. There were numerous research papers exploring “Higgsless theories” all the way up to the moment of Higgs boson discovery [2].

With significant opposition to the Higgs boson before its discovery it is not surprising that many are still loath to accept that what was found at CERN was indeed the Higgs boson elementary particle.

Why the animosity toward the Higgs boson?

Why do so many theoretical physicists really dislike the Higgs boson as a stand-alone elementary particle? One answer was from Harvard physicist Howard Georgi, who said that nature would be “malicious” if the Higgs boson were discovered since it would mean that nature would have skipped the opportunity to teach us new things [4]. Less reliant on human psychology, many theorists believed and still believe that a single Higgs boson elementary particle has a severe sickness. Let’s phrase it in the form of a conjecture:

The spin-less heavy elementary particle conjecture (SHEP conjecture): ordinary quantum field theory suggests to us that it is extraordinarily improbable that a spin-less elementary particle, like the purported Higgs boson, can have mass much less than the Planck mass, which is 16 orders of magnitude greater than the heaviest known elementary particle (i.e., Planck mass divided by top quark mass ~ 10^16).

The Planck mass is derived from gravitational physics and it is assumed that no elementary particle can have mass above it. Its numerical value is equivalent to about 10^19 hydrogen atoms, which is about 0.00002 grams. That sounds like a tiny and accessible mass, well below a pecan’s, so surely a particle could be that massive? But pecans are not “point-like” elementary particles, and it's the elementary particle by itself that has the Planck mass restriction inferred through quantum gravity considerations.

The SHEP conjecture is a claim based on the synthesis of hundreds of research papers on the so-called Naturalness, Hierarchy and Fine-tuning problem of the Higgs boson -- an amalgam of all the vulnerabilities perceived in the Higgs boson idea. We will not discuss the detailed reasons behind that and just go straight to its effect: Because of the SHEP conjecture few thought before the start of operations of CERN’s Large Hadron Collider that a Higgs boson would be discovered all alone, so light, trembling without an entourage of other particles or effects that would show us that the premises of the SHEP conjecture did not apply.

There had been already some evidence from previous experiments doing precision experiments on decays of the Z boson and precision mass determinations of the W boson (discovered in the 1980s) and the top quark (discovered in the 1990s) that a Higgs boson likely existed with mass less than the top quark mass (top quark mass = 186 hydrogen atoms). The research community was presented with the exciting prospect of discovery, but for those who accepted the dogma of the SHEP conjecture there was confusion and doubt about how it could exist. “I believe; help thou mine unbelief” is a pretty good summary of what most physicists felt. The resolution to the coexistence of the Higgs boson with the SHEP conjecture was that nature need only violate one or more premises of the SHEP conjecture and all would be well.

Violating the premises of the SHEP conjecture: supersymmetry

One can violate the premise of “ordinary quantum field theory” by introducing supersymmetry which is an exotic quantum field theory that has strict bindings between particles of different spins. A spin-less elementary particle, like the Higgs boson, would have to be paired with an elementary particle with spin, and that pairing immediately vacates the pressure that the spin-less particle has mass near the astronomically high Planck mass. The implications of supersymmetry is that many other particles -- superpartners to every known particle -- must exist and are discoverable if only colliders have enough energy to produce them.

Violating the premises of the SHEP conjecture: extra spatial dimensions

One can also manipulate the premise by adding extra spatial dimensions compactified into a tiny volume, which can have the effect of lowering the Planck mass from 10^16 times the Higgs boson mass to a value nearby. In that case, we satisfy the SHEP conjecture by saying that the Higgs boson is indeed not much less than the Planck scale. These extra dimensions are discoverable in principle, but in practice we don’t know how tiny the volume is for the extra spatial dimensions. The smaller this extra volume the higher energy we have to collide protons to see these dimensions unfold. (Don’t worry, it’s safe.)

Violating the premises of the SHEP conjecture: the Higgs boson is not elementary

Finally, one can violate the premises by assuming that the Higgs boson is simply not an elementary particle. It might be a composite particle like the proton or neutron, made up of smaller constituents [5]. Those smaller elementary particles that bind together to make the Higgs boson could be particles with spin, and then the SHEP conjecture would not apply and what we call the “Higgs boson” is a spin-less bound state of other particles whose spins cancel out, similar to what we see in superconductivity [6].

How to know if the Higgs boson is fictitious?

Each idea that we have discussed that allows the Higgs boson to exist but not violate the SHEP conjecture -- supersymmetry, new spatial dimensions, and compositeness -- implies that experiments in principle can see tiny deviations from what is otherwise expected if nature has only the pure elementary particle Higgs boson.

For example, experiments can count the number of times the Higgs boson decays into two photons. Under the assumption that the Higgs boson is strictly an elementary particle with no other additional features to support its existence, one can predict a value B for the number of times it decays into two photons. On the other hand, under the assumption that the Higgs boson exists in a more exotic way (again, supersymmetry, extra dimensions, or compositeness) the prediction will be a little different than B -- let’s call it B+x, where x is a small number compared to B.

At present, no final state decay of the Higgs boson is measured to better than 10%. In other words, the value of x can be as high as 10% of the value of B without running afoul of experimental results. So a theory of composite Higgs boson, or of supersymmetry or of extra dimensions, that predicts deviations that are less than 10% different from the predictions of an elementary Higgs boson is perfectly consistent with everything we know to date. Those who agree with the SHEP conjecture believe that these tiny deviations away from the elementary Higgs boson predictions will be seen if we can one day measure the Higgs boson decays with more precision.

So, physicists are not yet ready to call the Higgs boson a stand-alone elementary particle on the same level as we do an electron or a quark or a photon. We want to test all of the decays of the Higgs boson to better than a percent to give us more confidence ---the 10% determinations we have now are not good enough. We might be lucky and the CERN collider will discover small deviations as it collects more data starting next year. Or, more likely, we will have to wait for the proposed “Higgs factory” in Japan -- the International Linear Collider -- which has the ability to measure the Higgs boson properties to the sub-percent level and really test whether the Higgs boson can stand alone as a proud member of the elementary particle club like the electron, or whether it is fragile and reveals its supersymmetric, extra dimensional, or non-elementary heritage when we put it under a more powerful microscope.

References & End Notes

[1] M. Veltman. “Reflections on the Higgs system,” 17-21 March 1997, CERN. https://cds.cern.ch/record/334106

[2] J.D. Wells, “Beyond the Hypothesis: theory’s role in the genesis, opposition, and pursuit of the Higgs boson.” Stud.Hist.Phil.Sci B62, 36-44 (2018).

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S1355219816301551?via%3Dihub

[3] P. Anderson. “Higgs, Anderson, and all that”. Nature 11, 93 (2015).

https://www.nature.com/articles/nphys3247

[4] H. Georgi. “Why I would be very sad if a Higgs boson were discovered.” In Perspective on Higgs Physics II, ed. G.L. Kane. World Scientific, 1997.

[5] The prospect of the Higgs boson being composite is not so odd an assumption as it might appear on the surface, since there are bound states like that which already exist in nature, such as the pions. Pions are a class of particles with mass about 1/7th the mass of a hydrogen atom. They were first proposed by the Japanese physicist Hideki Yukawa in the 1930s in order to explain the strong force between protons and neutrons in the nucleus. Their experimental discovery was slow in coming, but by the 1950s they were firmly established empirically. However, it was not until the 1970s that it was understood that these pions are really just bound pairs of quarks and anti-quarks. Although the pions were spin-less, the constituent quarks that made the pions had spin that canceled out when paired. The Higgs boson could be a bound state analogous to the pion. “If nature can do it once, it can do it again,” was the rallying cry.

[6] Some materials when cooled to sufficiently low temperatures become perfect conductors of electricity -- superconductivity. The microscopic reason for why that happens is the formation of Cooper pairs, where two electrons, which have spin, bind in the material and form a spin-less boson very similar to the structure of a Higgs boson. If nature does it in superconductivity, maybe it can do the same thing for elementary particles. This line of thought led the Nobel Laureate physicist Phil Anderson, who is a condensed matter physicist that knows very little about particle physics, to declare in 2015 three years after the Higgs boson discovery that “maybe the Higgs boson is fictitious!” [3], as though we particle physicists had never thought about that possibility.

In Mice, High-Fat Diets Seem to Foster Cancers Involving Immune Cells

I have argued that cancer cells are often metabolically damaged and can more easily digest sugar and certain amino acids than fat:

Meat Is Amazingly Nutritious—But Is It Amazingly Nutritious for Cancer Cells, Too?

Cancer Cells Love Sugar; That’s How PET Scans for Cancer Work

So it is important to engage with a study that claims that high-fat diets are cancer promoting—at least on the surface the opposite to my claim that high-fat diets—and fasting, which puts body fat in the bloodstream—are hard on cancer.

There are several points I want to make.

First, many high-fat diets are also high in protein. The fat can easily get blamed for the cancer-promoting effects of the protein.

Second, mice are naturally adapted to high-carb diets; because mouse generations are much shorter than human generations mice are likely to be much, much better adapted to the human agricultural revolution than humans are. Fat is a relatively unusual diet component for mice. Thus, healthy mouse cells may be ill-adapted to process fat, while mouse cancer cells explore a wider set of possibilities. By contrast, until a few generations ago, a substantial amount of sugar was quite unusual for humans. Now, cancer cells may adapt to sugar-rich diets better than healthy cells.

Third, that the mouse finding about high-fat diets and tumor growth was limited to cancers with many immune cells is implicitly suggesting that other mouse cancers are not that great at drawing in and metabolizing fat. This may be the weakest of my three arguments for the simple reason that immune cells that become cancerous are probably key to metastasis: cancer cells migrating from one part of the body to another. Metastasis is often what makes cancers deadly. So immune cells becoming cancerous is a big deal.

In any case, high-fat diets in humans tend to lead to lower obesity compared to high-sugar diets. So Kevin Jiang’s Harvard Gazette article ‘A metabolic tug-of-war’ is off base to invoke the relationship between cancer and obesity in humans as something that is related to high-fat diets promoting certain types of cancer in mice. High-fat diets do tend to promote obesity in mice, so relating a correlation between obesity and cancer to a correlation between a high-fat-diet and cancer is more appropriate if the discussion is entirely restricted to mice.

What I worry about with this Harvard Gazette article is that people will read it through the lens of the traditional view that high-fat diets are bad for humans—a view that has not done very well at standing the test of time. To repeat, I think there is decent evidence that high-protein diets cause cancer—especially diets high in animal protein. Don’t blame dietary fat as cancer-causing unless you have carefully held the amount of protein and especially animal protein constant. And while mouse results can illuminate human biology in many areas, the great difference in the diet mice are adapted for compared to the diet humans are adapted for makes mouse evidence suspect when it comes to comparing high-carb to high-fat diets.

For annotated links to other posts on diet and health, see:

The Federalist Papers #22 A: The Articles of Confederation Lead to Uncoordinated Trade Policy and Military Free-Riding—Alexander Hamilton

In the absence of subgame-perfect enforcement mechanisms (where “subgame-perfect” means enforcement mechanisms that are OK enough that people are willing to use them), game theory suggests that it is easy to get into an “everyone-out-for-self” equilibrium. In the Federalist Papers #22, Alexander Hamilton begins by saying that the Articles of Confederation led toward an “everyone-out-for-self” equilibrium in both trade policy and in putting together an army.

The lack of a coordinated trade policy led to difficulties in negotiating favorable trade treaties with other countries:

No nation acquainted with the nature of our political association would be unwise enough to enter into stipulations with the United States, by which they conceded privileges of any importance to them, while they were apprised that the engagements on the part of the Union might at any moment be violated by its members, and while they found from experience that they might enjoy every advantage they desired in our markets, without granting us any return but such as their momentary convenience might suggest.

Uncoordinated trade policy also presented the danger of destroying a single market for the United States and in that process creating animosity between states:

The interfering and unneighborly regulations of some States … if not restrained by a national control, would be multiplied and extended till they became not less serious sources of animosity and discord than injurious impediments to the intercourse between the different parts of the Confederacy.

Lack of coordination in raising an army forfeited the monopsony power the government could otherwise have had in hiring troops (note that Alexander Hamilton seems to assume that a draft is not feasible):

The power of raising armies, by the most obvious construction of the articles of the Confederation, is merely a power of making requisitions upon the States for quotas of men. This practice … gave birth to a competition between the States which created a kind of auction for men. In order to furnish the quotas required of them, they outbid each other till bounties grew to an enormous and insupportable size.

Moreover, states not immediately threatened by enemy troops shirked in providing troops, thereby “free-riding” on the military efforts of the states closer to the fighting:

The States near the seat of war, influenced by motives of self-preservation, made efforts to furnish their quotas, which even exceeded their abilities; while those at a distance from danger were, for the most part, as remiss as the others were diligent, in their exertions.

These arguments seem persuasive, though needing to be combined with many other arguments to make a truly strong case for “a more perfect union” than the weak Articles of Confederation.

Below is the full text of the first part of the Federalist Papers #22. (I have inserted the text of footnotes within brackets in the main text.)

FEDERALIST NO. 22

The Same Subject Continued: Other Defects of the Present Confederation

From the New York Packet

Friday, December 14, 1787.

Author: Alexander Hamilton

To the People of the State of New York:

IN ADDITION to the defects already enumerated in the existing federal system, there are others of not less importance, which concur in rendering it altogether unfit for the administration of the affairs of the Union.

The want of a power to regulate commerce is by all parties allowed to be of the number. The utility of such a power has been anticipated under the first head of our inquiries; and for this reason, as well as from the universal conviction entertained upon the subject, little need be added in this place. It is indeed evident, on the most superficial view, that there is no object, either as it respects the interests of trade or finance, that more strongly demands a federal superintendence. The want of it has already operated as a bar to the formation of beneficial treaties with foreign powers, and has given occasions of dissatisfaction between the States. No nation acquainted with the nature of our political association would be unwise enough to enter into stipulations with the United States, by which they conceded privileges of any importance to them, while they were apprised that the engagements on the part of the Union might at any moment be violated by its members, and while they found from experience that they might enjoy every advantage they desired in our markets, without granting us any return but such as their momentary convenience might suggest. It is not, therefore, to be wondered at that Mr. Jenkinson, in ushering into the House of Commons a bill for regulating the temporary intercourse between the two countries, should preface its introduction by a declaration that similar provisions in former bills had been found to answer every purpose to the commerce of Great Britain, and that it would be prudent to persist in the plan until it should appear whether the American government was likely or not to acquire greater consistency. [This, as nearly as I can recollect, was the sense of his speech on introducing the last bill.]

Several States have endeavored, by separate prohibitions, restrictions, and exclusions, to influence the conduct of that kingdom in this particular, but the want of concert, arising from the want of a general authority and from clashing and dissimilar views in the State, has hitherto frustrated every experiment of the kind, and will continue to do so as long as the same obstacles to a uniformity of measures continue to exist.

The interfering and unneighborly regulations of some States, contrary to the true spirit of the Union, have, in different instances, given just cause of umbrage and complaint to others, and it is to be feared that examples of this nature, if not restrained by a national control, would be multiplied and extended till they became not less serious sources of animosity and discord than injurious impediments to the intercourse between the different parts of the Confederacy. "The commerce of the German empire [Encyclopedia, article "Empire."] is in continual trammels from the multiplicity of the duties which the several princes and states exact upon the merchandises passing through their territories, by means of which the fine streams and navigable rivers with which Germany is so happily watered are rendered almost useless." Though the genius of the people of this country might never permit this description to be strictly applicable to us, yet we may reasonably expect, from the gradual conflicts of State regulations, that the citizens of each would at length come to be considered and treated by the others in no better light than that of foreigners and aliens.

The power of raising armies, by the most obvious construction of the articles of the Confederation, is merely a power of making requisitions upon the States for quotas of men. This practice in the course of the late war, was found replete with obstructions to a vigorous and to an economical system of defense. It gave birth to a competition between the States which created a kind of auction for men. In order to furnish the quotas required of them, they outbid each other till bounties grew to an enormous and insupportable size. The hope of a still further increase afforded an inducement to those who were disposed to serve to procrastinate their enlistment, and disinclined them from engaging for any considerable periods. Hence, slow and scanty levies of men, in the most critical emergencies of our affairs; short enlistments at an unparalleled expense; continual fluctuations in the troops, ruinous to their discipline and subjecting the public safety frequently to the perilous crisis of a disbanded army. Hence, also, those oppressive expedients for raising men which were upon several occasions practiced, and which nothing but the enthusiasm of liberty would have induced the people to endure.

This method of raising troops is not more unfriendly to economy and vigor than it is to an equal distribution of the burden. The States near the seat of war, influenced by motives of self-preservation, made efforts to furnish their quotas, which even exceeded their abilities; while those at a distance from danger were, for the most part, as remiss as the others were diligent, in their exertions. The immediate pressure of this inequality was not in this case, as in that of the contributions of money, alleviated by the hope of a final liquidation. The States which did not pay their proportions of money might at least be charged with their deficiencies; but no account could be formed of the deficiencies in the supplies of men. We shall not, however, see much reason to reget the want of this hope, when we consider how little prospect there is, that the most delinquent States will ever be able to make compensation for their pecuniary failures. The system of quotas and requisitions, whether it be applied to men or money, is, in every view, a system of imbecility in the Union, and of inequality and injustice among the members.

Here are links to my other posts on The Federalist Papers so far:

The Federalist Papers #1: Alexander Hamilton's Plea for Reasoned Debate

The Federalist Papers #3: United, the 13 States are Less Likely to Stumble into War

The Federalist Papers #4 B: National Defense Will Be Stronger if the States are United

The Federalist Papers #5: Unless United, the States Will Be at Each Others' Throats

The Federalist Papers #6 A: Alexander Hamilton on the Many Human Motives for War

The Federalist Papers #11 A: United, the States Can Get a Better Trade Deal—Alexander Hamilton

The Federalist Papers #12: Union Makes it Much Easier to Get Tariff Revenue—Alexander Hamilton

The Federalist Papers #13: Alexander Hamilton on Increasing Returns to Scale in National Government

The Federalist Papers #14: A Republic Can Be Geographically Large—James Madison

The Federalist Papers #21 A: Constitutions Need to be Enforced—Alexander Hamilton

How Fast Should a Project Be Completed?

One of my current non-work projects is to learn German. My goal is to be able to read German; speaking it would be a bonus, but not as important to me. Having had a year of college German and listened responsively to the 5 levels of Pimsleur German (which I highly recommend), I don’t need more grammar for my purposes, just vocabulary. I was pleased to discover in a set of 4 “German Frequency Dictionaries” 10,000 German words listed in order of frequency with excellent example sentences, and part-of-speech lists. (I have to confess that the example sentences often emphasize interpersonal conflict!)

All I have to do is learn 10,000 words and I’ll be able to read German. (The books claim that only 5% of written German words are outside the top 10,000 words, and I figure those 5% are likely to be quite genre-specific and therefore quick to pick up for any given genre.)

But how hard should I work on learning German each day? Let me approach this as an abstract optimization problem that could be applied to other similar problems. (Brownie points are available for suggesting in a comment other problems the following math is relevant for.)

First, notation:

The idea is then to minimize the total cost, which equals the daily cost times the number of days to completion:

Minimizing the natural logarithm of the total cost has the same optimal speed:

The first-order condition for the logarithmic version of the problem is:

Rearranging the algebra, the first-order condition becomes:

This has a nice interpretation: the elasticity of the daily cost of speed should be set equal to the ratio by which the total cost (including both the cost of speed and the cost of delay) exceeds the cost of speed alone.

If the daily cost of speed is increasing in speed, the right-hand side of this first order condition is decreasing in x. If, in addition, the elasticity of the daily cost of speed is increasing in speed, then any solution to the first-order condition will provide a unique solution for the optimal speed. Not surprisingly, for a given functional form of the cost of speed, the optimal speed will be higher the higher the cost of delay.

To me, this suggests that I should study German relatively fast. I don’t like not being able to read German. I think I have identified the right technology for learning it, having done Pimsleur German, with the books I have and using the memory techniques I talk about in “The Most Effective Memory Methods are Difficult—and That's Why They Work.” And on any day that is only medium busy (a little easier to come by during this pandemic), I don’t think the elasticity of the daily cost rises much above one until I get above an hour a day on German study.

See if this kind of logic helps you with any practical decision that you have. Basically, it says we should get things done fast unless there is a relatively-quickly-increasing cost to speed.

The extension to multiple projects each with this kind of costs and benefits turns out to be very interesting. I plan to do another blog post or two on that in the new year.