How to Reduce Date Rape

Malcolm Gladwell has two big themes in his book Talking to Strangers. The first theme is that we are very bad at telling whether someone is lying or not. Many of us think we are good at it, but we are not, not even professionals whose job it is to tell when someone is lying. Scarily, some people just naturally look like they are lying even when they aren’t, while others naturally look like they are telling the truth when they are really lying. Unfortunately, but also possibly flattering myself, I suspect that I personally am in the category of people who look like they are lying even when they are telling the truth. (For example, I am not great at eye contact.) Those who know me well probably realize this and correct for it. But in a police interrogation room or a court of law being judged by strangers, I might get in trouble.

Malcolm Gladwell’s second theme is one dear to social psychologists: the effect of situations on behavior relative to the effect of character on behavior is much bigger than people assume.

Let me turn to a particular example. In discussing date rape, most of the discussion focuses on men being bad. But there is a dramatically important situational element to most date rapes: alcohol intoxication—and sometimes intoxication with other drugs.

I want to make a simple proposal that I think could make a real dent in date rape. Just as we have laws making it statutory rape to have sex or sexual activities with anyone under a certain age, make it statutory rape to have sex or sexual activities with anyone who is too intoxicated to legally drive, at least as the default.

Here is what I mean by “at least as a default.” Have an opt-in procedure on a secure state government website to increase the blood alcohol level at which sex with you isn’t statutory rape either for sex or sexual activities with specific individuals (say, one’s boyfriend or girlfriend) or to increase that cutoff blood alcohol level in general for any partner. (There is no reason not to give you several options for the cutoff blood alcohol level.)

All the current laws about consent would continue to apply. It is simply what level of blood alcohol legally constitutes automatic, crystal-clear no-consent that would change if one opted in to a different level on the state government website.

There is no need to make it public what choice you have made on the state government website. As long as you are over 18, you shouldn’t have to worry about your parents knowing. Even with your choices password-protected, you will be able to demonstrate what choice you have made to a potential sexual partner if they want reassurance that you are “legal” to have sex or sexual activities with.

In addition to helping discourage date rape enabled by alcohol, I think this would have the beneficial side effect of making it easier in general for people who don’t want sex to say no even in the face of some degree of pressure to have sex, and so help a bit in avoiding cases of genuine, but reluctant consent.

I want to emphasize that the opt-in capability means that anyone who doesn’t want any level of alcohol intoxication short of the blackout level to get in the way of any sexual encounter has that choice. Defaults matter a lot, but if you don’t like the default, you have the choice of having things as they are now for yourself. Of course, if you enjoy taking sexual advantage of others because they are intoxicated, too bad. This policy change would prevent you from doing some of the harm you want to do.

Postscript: If state governments don’t take up this idea, a college or university could do something quite similar on its own, with the one change that the penalty for having sex with someone who was inebriated without them having opted in (if that was the only infraction) would only have a penalty of expulsion.

Note that it is probably necessary to have students and employees of the college or university to give consent for blood alcohol tests as a condition of studying or being employed by the college or university.

It is possible this policy might discourage some men from attending that college or university. But the college or university is probably better off without those particular men. And, as long as the opt-in policy is made clear, it should make women more eager to attend that college or university.

Postpostscript: You might worry that a sexual aggressor could threaten to countercharge the one assaulted with statutory rape. But if someone had sex reluctantly with an aggressor who was over the blood alcohol cutoff, that reluctance would be a defence against the charge of statutory rape. I think juries would normally believe that someone who was, in fact, reluctant was telling the truth about their reluctance. So I don’t think there is a big problem there, in practice.

Have We Gone Too Far with Sunscreen?

Link to the article shown above

Deaths from heart disease are orders of magnitude more common than deaths from skin cancer. So it makes sense to do things that reduce heart disease risk even at the cost of some increase in skin cancer risk. Sun exposure seems to have exactly this tradeoff: a modest but important reduction in heart disease risk accompanied by a modest increase in skin cancer risk. But the modest increase in skin cancer risk corresponds to a much, much smaller number of deaths. Some experts claim that the reduction in heart disease risk from sun exposure can be fully replicated by drugs that reduce heart disease. But that seems unlikely to me. We are evolutionarily adapted to a fair amount of sun exposure, and quite a few different bodily mechanisms may be predicated on sun exposure; anti-heart-disease drugs may only replicate or imitate a few of these mechanisms.

The importance of sun exposure is shown by the fact that people whose ancestors lived in northern climes are white. Enough people died from insufficient sun exposure that those of us with northern ancestry are preferentially descended from people whose skin let more sunlight in by being white. Note that this implies that those with ancestry from nearer the equator might need as much sun exposure as they can get, and would be ill-advised to use sunscreen that blocks out any physiologically useful component of sunlight. (That in turn would imply that sunscreen marketing to these folks would worsen racial inequality in health.)

I come to these views from reading the persuasive article “Is Sunscreen the New Margarine?” by Rowan Jacobsen. The bottom-line recommendation I take is that as long as you strenuously avoid getting a sunburn (even a mild one), and keep sunlight out of your eyes, sunshine on bare skin is good for you. (However, at the high end of this non-sunburn range, that much sun exposure may have long-run negative cosmetic effects—such as leathery skin—that you care about.)

I recommend that you read the whole article “Is Sunscreen the New Margarine?” but to convince you to take that recommendation, let quote some of the passages that most struck me as teasers. I’ll separate passages with my own added bullets.

If there was one supplement that seemed sure to survive the rigorous tests, it was vitamin D. People with low levels of vitamin D in their blood have significantly higher rates of virtually every disease and disorder you can think of: cancer, diabetes, obesity, osteoporosis, heart attack, stroke, depression, cognitive impairment, autoimmune conditions, and more. The vitamin is required for calcium absorption and is thus essential for bone health, but as evidence mounted that lower levels of vitamin D were associated with so many diseases, health experts began suspecting that it was involved in many other biological processes as well.

Yet vitamin D supplementation has failed spectacularly in clinical trials. Five years ago, researchers were already warning that it showed zero benefit, and the evidence has only grown stronger. In November, one of the largest and most rigorous trials of the vitamin ever conducted—in which 25,871 participants received high doses for five years—found no impact on cancer, heart disease, or stroke.

These rebels argue that what made the people with high vitamin D levels so healthy was not the vitamin itself. That was just a marker. Their vitamin D levels were high because they were getting plenty of exposure to the thing that was really responsible for their good health—that big orange ball shining down from above.

… today most of us have indoor jobs, and when we do go outside, we’ve been taught to protect ourselves from dangerous UV rays, which can cause skin cancer. Sunscreen also blocks our skin from making vitamin D, but that’s OK, says the American Academy of Dermatology, which takes a zero-tolerance stance on sun exposure: “You need to protect your skin from the sun every day, even when it’s cloudy,” it advises on its website. Better to slather on sunblock, we’ve all been told, and compensate with vitamin D pills.

Weller’s doubts began around 2010, when he was researching nitric oxide, a molecule produced in the body that dilates blood vessels and lowers blood pressure. He discovered a previously unknown biological pathway by which the skin uses sunlight to make nitric oxide.

It was already well established that rates of high blood pressure, heart disease, stroke, and overall mortality all rise the farther you get from the sunny equator, and they all rise in the darker months. Weller put two and two together and had what he calls his “eureka moment”: Could exposing skin to sunlight lower blood pressure?

Sure enough, when he exposed volunteers to the equivalent of 30 minutes of summer sunlight without sunscreen, their nitric oxide levels went up and their blood pressure went down. Because of its connection to heart disease and strokes, blood pressure is the leading cause of premature death and disease in the world, and the reduction was of a magnitude large enough to prevent millions of deaths on a global level.

Wouldn’t all those rays also raise rates of skin cancer? Yes, but skin cancer kills surprisingly few people: less than 3 per 100,000 in the U.S. each year. For every person who dies of skin cancer, more than 100 die from cardiovascular diseases.

People don’t realize this because several different diseases are lumped together under the term “skin cancer.” The most common by far are basal-cell carcinomas and squamous-cell carcinomas, which are almost never fatal.

Melanoma, the deadly type of skin cancer, is much rarer, accounting for only 1 to 3 percent of new skin cancers. And perplexingly, outdoor workers have half the melanoma rate of indoor workers. Tanned people have lower rates in general. “The risk factor for melanoma appears to be intermittent sunshine and sunburn, especially when you’re young,” says Weller. “But there’s evidence that long-term sun exposure associates with less melanoma.”

Lindqvist tracked the sunbathing habits of nearly 30,000 women in Sweden over 20 years. Originally, he was studying blood clots, which he found occurred less frequently in women who spent more time in the sun—and less frequently during the summer. Lindqvist looked at diabetes next. Sure enough, the sun worshippers had much lower rates. Melanoma? True, the sun worshippers had a higher incidence of it—but they were eight times less likely to die from it.

So Lindqvist decided to look at overall mortality rates, and the results were shocking. Over the 20 years of the study, sun avoiders were twice as likely to die as sun worshippers.

When I spoke with Weller, I made the mistake of characterizing this notion as counterintuitive. “It’s entirely intuitive,” he responded. “Homo sapiens have been around for 200,000 years. Until the industrial revolution, we lived outside. How did we get through the Neolithic Era without sunscreen? Actually, perfectly well. What’s counterintuitive is that dermatologists run around saying, ‘Don’t go outside, you might die.’”

Meanwhile, that big picture just keeps getting more interesting. Vitamin D now looks like the tip of the solar iceberg. Sunlight triggers the release of a number of other important compounds in the body, not only nitric oxide but also serotonin and endorphins. It reduces the risk of prostate, breast, colorectal, and pancreatic cancers. It improves circadian rhythms. It reduces inflammation and dampens autoimmune responses. It improves virtually every mental condition you can think of. And it’s free.

… the current U.S. sun-exposure guidelines were written for the whitest people on earth.

…

African Americans suffer high rates of diabetes, heart disease, stroke, internal cancers, and other diseases that seem to improve in the presence of sunlight, of which they may well not be getting enough.

… early sunscreen formulations were disastrous, shielding users from the UVB rays that cause sunburn but not the UVA rays that cause skin cancer. Even today, SPF ratings refer only to UVB rays, so many users may be absorbing far more UVA radiation than they realize. Meanwhile, many common sunscreen ingredients have been found to be hormone disruptors that can be detected in users’ blood and breast milk. The worst offender, oxybenzone, also mutates the DNA of corals and is believed to be killing coral reefs. Hawaii and the western Pacific nation of Palau have already banned it, to take effect in 2021 and 2020 respectively, and other governments are expected to follow.

… many experts in the rest of the world have already come around to the benefits of sunlight. Sunny Australia changed its tune back in 2005. Cancer Council Australia’s official-position paper (endorsed by the Australasian College of Dermatologists) states, “Ultraviolet radiation from the sun has both beneficial and harmful effects on human health.... A balance is required between excessive sun exposure which increases the risk of skin cancer and enough sun exposure to maintain adequate vitamin D levels.... It should be noted that the benefits of sun exposure may extend beyond the production of vitamin D. Other possible beneficial effects of sun exposure… include reduction in blood pressure, suppression of autoimmune disease, and improvements in mood.”

New Zealand signed on to similar recommendations, and the British Association of Dermatologists went even further in a statement, directly contradicting the position of its American counterpart: “Enjoying the sun safely, while taking care not to burn, can help to provide the benefits of vitamin D without unduly raising the risk of skin cancer.”

For annotated links to other posts on diet and health, see:

Stanley K. Ridgley Against Robin DeAngelo, Author of 'White Fragility' →

Because I mentioned Robin DeAngelo’s book White Fragility in a positive way in two blog posts, “Enablers of White Supremacy” and “How Even Liberal Whites Make Themselves Out as Victims in Discussions of Racism,” I consider it important to give the other side about Robin DeAngelo. Here is a link to Stanley K. Ridgley’s essay critical of Robin DeAngelo.

I don’t think my two blog posts are seriously vitiated by this; they were based on my imagined picture of how a racial sensitivity training along these lines might go, not on the reality of what Robin DeAngelo does. It may well be that my imagined picture is considerably more benign than the reality of what Robin DeAngelo does.

On this topic of racial sensitivity training, I also have a more recent post: “Thinking about the 'Executive Order on Combating Race and Sex Stereotyping'.”

The Federalist Papers #19: The Weakness of the German Empire, Poland and Switzerland up to the 18th Century is Evidence for the Weakness of Confederations—Alexander Hamilton and James Madison

I enjoy the Federalist Papers #19 for its detailed political science discussion of the German Empire, which played such a major—but not always powerful—part in European history. Alexander Hamilton and James Madison also discuss Poland and Switzerland as examples of confederacies. This one is fun for history buffs. I won’t try to summarize everything; I hope you’ll read it. However, I’ll lay out some of my favorite passages:

The German Empire up to 1787:

From such a parade of constitutional powers, in the representatives and head of this confederacy, the natural supposition would be, that it must form an exception to the general character which belongs to its kindred systems. Nothing would be further from the reality. The fundamental principle on which it rests, that the empire is a community of sovereigns, that the diet is a representation of sovereigns and that the laws are addressed to sovereigns, renders the empire a nerveless body, incapable of regulating its own members, insecure against external dangers, and agitated with unceasing fermentations in its own bowels.

In the sixteenth century, the emperor, with one part of the empire on his side, was seen engaged against the other princes and states. In one of the conflicts, the emperor himself was put to flight, and very near being made prisoner by the elector of Saxony. The late king of Prussia was more than once pitted against his imperial sovereign; and commonly proved an overmatch for him.

Previous to the peace of Westphalia, Germany was desolated by a war of thirty years, in which the emperor, with one half of the empire, was on one side, and Sweden, with the other half, on the opposite side. Peace was at length negotiated, and dictated by foreign powers; and the articles of it, to which foreign powers are parties, made a fundamental part of the Germanic constitution.

We may form some judgment of this scheme of military coercion from a sample given by Thuanus. In Donawerth, a free and imperial city of the circle of Suabia, the Abb 300 de St. Croix enjoyed certain immunities which had been reserved to him. In the exercise of these, on some public occasions, outrages were committed on him by the people of the city. The consequence was that the city was put under the ban of the empire, and the Duke of Bavaria, though director of another circle, obtained an appointment to enforce it. He soon appeared before the city with a corps of ten thousand troops, and finding it a fit occasion, as he had secretly intended from the beginning, to revive an antiquated claim, on the pretext that his ancestors had suffered the place to be dismembered from his territory, he took possession of it in his own name, disarmed, and punished the inhabitants, and reannexed the city to his domains.

Nor is it to be imagined, if this obstacle could be surmounted, that the neighboring powers would suffer a revolution to take place which would give to the empire the force and preeminence to which it is entitled. Foreign nations have long considered themselves as interested in the changes made by events in this constitution; and have, on various occasions, betrayed their policy of perpetuating its anarchy and weakness.

Poland up to 1787:

If more direct examples were wanting, Poland, as a government over local sovereigns, might not improperly be taken notice of. Nor could any proof more striking be given of the calamities flowing from such institutions. Equally unfit for self-government and self-defense, it has long been at the mercy of its powerful neighbors; who have lately had the mercy to disburden it of one third of its people and territories.

The Swiss Confederation up to 1787:

Whatever efficacy the union may have had in ordinary cases, it appears that the moment a cause of difference sprang up, capable of trying its strength, it failed. The controversies on the subject of religion, which in three instances have kindled violent and bloody contests, may be said, in fact, to have severed the league. The Protestant and Catholic cantons have since had their separate diets, where all the most important concerns are adjusted, and which have left the general diet little other business than to take care of the common bailages.

That separation had another consequence, which merits attention. It produced opposite alliances with foreign powers: of Berne, at the head of the Protestant association, with the United Provinces; and of Luzerne, at the head of the Catholic association, with France.

Here is the full text of the Federalist Papers #19:

FEDERALIST NO. 19

The Same Subject Continued: The Insufficiency of the Present Confederation to Preserve the Union

For the Independent Journal.

Author: Alexander Hamilton and James Madison

To the People of the State of New York:

THE examples of ancient confederacies, cited in my last paper, have not exhausted the source of experimental instruction on this subject. There are existing institutions, founded on a similar principle, which merit particular consideration. The first which presents itself is the Germanic body.

In the early ages of Christianity, Germany was occupied by seven distinct nations, who had no common chief. The Franks, one of the number, having conquered the Gauls, established the kingdom which has taken its name from them. In the ninth century Charlemagne, its warlike monarch, carried his victorious arms in every direction; and Germany became a part of his vast dominions. On the dismemberment, which took place under his sons, this part was erected into a separate and independent empire. Charlemagne and his immediate descendants possessed the reality, as well as the ensigns and dignity of imperial power. But the principal vassals, whose fiefs had become hereditary, and who composed the national diets which Charlemagne had not abolished, gradually threw off the yoke and advanced to sovereign jurisdiction and independence. The force of imperial sovereignty was insufficient to restrain such powerful dependants; or to preserve the unity and tranquillity of the empire. The most furious private wars, accompanied with every species of calamity, were carried on between the different princes and states. The imperial authority, unable to maintain the public order, declined by degrees till it was almost extinct in the anarchy, which agitated the long interval between the death of the last emperor of the Suabian, and the accession of the first emperor of the Austrian lines. In the eleventh century the emperors enjoyed full sovereignty: In the fifteenth they had little more than the symbols and decorations of power.

Out of this feudal system, which has itself many of the important features of a confederacy, has grown the federal system which constitutes the Germanic empire. Its powers are vested in a diet representing the component members of the confederacy; in the emperor, who is the executive magistrate, with a negative on the decrees of the diet; and in the imperial chamber and the aulic council, two judiciary tribunals having supreme jurisdiction in controversies which concern the empire, or which happen among its members.

The diet possesses the general power of legislating for the empire; of making war and peace; contracting alliances; assessing quotas of troops and money; constructing fortresses; regulating coin; admitting new members; and subjecting disobedient members to the ban of the empire, by which the party is degraded from his sovereign rights and his possessions forfeited. The members of the confederacy are expressly restricted from entering into compacts prejudicial to the empire; from imposing tolls and duties on their mutual intercourse, without the consent of the emperor and diet; from altering the value of money; from doing injustice to one another; or from affording assistance or retreat to disturbers of the public peace. And the ban is denounced against such as shall violate any of these restrictions. The members of the diet, as such, are subject in all cases to be judged by the emperor and diet, and in their private capacities by the aulic council and imperial chamber.

The prerogatives of the emperor are numerous. The most important of them are: his exclusive right to make propositions to the diet; to negative its resolutions; to name ambassadors; to confer dignities and titles; to fill vacant electorates; to found universities; to grant privileges not injurious to the states of the empire; to receive and apply the public revenues; and generally to watch over the public safety. In certain cases, the electors form a council to him. In quality of emperor, he possesses no territory within the empire, nor receives any revenue for his support. But his revenue and dominions, in other qualities, constitute him one of the most powerful princes in Europe.

From such a parade of constitutional powers, in the representatives and head of this confederacy, the natural supposition would be, that it must form an exception to the general character which belongs to its kindred systems. Nothing would be further from the reality. The fundamental principle on which it rests, that the empire is a community of sovereigns, that the diet is a representation of sovereigns and that the laws are addressed to sovereigns, renders the empire a nerveless body, incapable of regulating its own members, insecure against external dangers, and agitated with unceasing fermentations in its own bowels.

The history of Germany is a history of wars between the emperor and the princes and states; of wars among the princes and states themselves; of the licentiousness of the strong, and the oppression of the weak; of foreign intrusions, and foreign intrigues; of requisitions of men and money disregarded, or partially complied with; of attempts to enforce them, altogether abortive, or attended with slaughter and desolation, involving the innocent with the guilty; of general inbecility, confusion, and misery.

In the sixteenth century, the emperor, with one part of the empire on his side, was seen engaged against the other princes and states. In one of the conflicts, the emperor himself was put to flight, and very near being made prisoner by the elector of Saxony. The late king of Prussia was more than once pitted against his imperial sovereign; and commonly proved an overmatch for him. Controversies and wars among the members themselves have been so common, that the German annals are crowded with the bloody pages which describe them. Previous to the peace of Westphalia, Germany was desolated by a war of thirty years, in which the emperor, with one half of the empire, was on one side, and Sweden, with the other half, on the opposite side. Peace was at length negotiated, and dictated by foreign powers; and the articles of it, to which foreign powers are parties, made a fundamental part of the Germanic constitution.

If the nation happens, on any emergency, to be more united by the necessity of self-defense, its situation is still deplorable. Military preparations must be preceded by so many tedious discussions, arising from the jealousies, pride, separate views, and clashing pretensions of sovereign bodies, that before the diet can settle the arrangements, the enemy are in the field; and before the federal troops are ready to take it, are retiring into winter quarters.

The small body of national troops, which has been judged necessary in time of peace, is defectively kept up, badly paid, infected with local prejudices, and supported by irregular and disproportionate contributions to the treasury.

The impossibility of maintaining order and dispensing justice among these sovereign subjects, produced the experiment of dividing the empire into nine or ten circles or districts; of giving them an interior organization, and of charging them with the military execution of the laws against delinquent and contumacious members. This experiment has only served to demonstrate more fully the radical vice of the constitution. Each circle is the miniature picture of the deformities of this political monster. They either fail to execute their commissions, or they do it with all the devastation and carnage of civil war. Sometimes whole circles are defaulters; and then they increase the mischief which they were instituted to remedy.

We may form some judgment of this scheme of military coercion from a sample given by Thuanus. In Donawerth, a free and imperial city of the circle of Suabia, the Abb 300 de St. Croix enjoyed certain immunities which had been reserved to him. In the exercise of these, on some public occasions, outrages were committed on him by the people of the city. The consequence was that the city was put under the ban of the empire, and the Duke of Bavaria, though director of another circle, obtained an appointment to enforce it. He soon appeared before the city with a corps of ten thousand troops, and finding it a fit occasion, as he had secretly intended from the beginning, to revive an antiquated claim, on the pretext that his ancestors had suffered the place to be dismembered from his territory,[ Pfeffel, "Nouvel Abreg. Chronol. de l'Hist., etc., d'Allemagne," says the pretext was to indemnify himself for the expense of the expedition.] he took possession of it in his own name, disarmed, and punished the inhabitants, and reannexed the city to his domains.

It may be asked, perhaps, what has so long kept this disjointed machine from falling entirely to pieces? The answer is obvious: The weakness of most of the members, who are unwilling to expose themselves to the mercy of foreign powers; the weakness of most of the principal members, compared with the formidable powers all around them; the vast weight and influence which the emperor derives from his separate and heriditary dominions; and the interest he feels in preserving a system with which his family pride is connected, and which constitutes him the first prince in Europe; --these causes support a feeble and precarious Union; whilst the repellant quality, incident to the nature of sovereignty, and which time continually strengthens, prevents any reform whatever, founded on a proper consolidation. Nor is it to be imagined, if this obstacle could be surmounted, that the neighboring powers would suffer a revolution to take place which would give to the empire the force and preeminence to which it is entitled. Foreign nations have long considered themselves as interested in the changes made by events in this constitution; and have, on various occasions, betrayed their policy of perpetuating its anarchy and weakness.

If more direct examples were wanting, Poland, as a government over local sovereigns, might not improperly be taken notice of. Nor could any proof more striking be given of the calamities flowing from such institutions. Equally unfit for self-government and self-defense, it has long been at the mercy of its powerful neighbors; who have lately had the mercy to disburden it of one third of its people and territories.

The connection among the Swiss cantons scarcely amounts to a confederacy; though it is sometimes cited as an instance of the stability of such institutions.

They have no common treasury; no common troops even in war; no common coin; no common judicatory; nor any other common mark of sovereignty.

They are kept together by the peculiarity of their topographical position; by their individual weakness and insignificancy; by the fear of powerful neighbors, to one of which they were formerly subject; by the few sources of contention among a people of such simple and homogeneous manners; by their joint interest in their dependent possessions; by the mutual aid they stand in need of, for suppressing insurrections and rebellions, an aid expressly stipulated and often required and afforded; and by the necessity of some regular and permanent provision for accomodating disputes among the cantons. The provision is, that the parties at variance shall each choose four judges out of the neutral cantons, who, in case of disagreement, choose an umpire. This tribunal, under an oath of impartiality, pronounces definitive sentence, which all the cantons are bound to enforce. The competency of this regulation may be estimated by a clause in their treaty of 1683, with Victor Amadeus of Savoy; in which he obliges himself to interpose as mediator in disputes between the cantons, and to employ force, if necessary, against the contumacious party.

So far as the peculiarity of their case will admit of comparison with that of the United States, it serves to confirm the principle intended to be established. Whatever efficacy the union may have had in ordinary cases, it appears that the moment a cause of difference sprang up, capable of trying its strength, it failed. The controversies on the subject of religion, which in three instances have kindled violent and bloody contests, may be said, in fact, to have severed the league. The Protestant and Catholic cantons have since had their separate diets, where all the most important concerns are adjusted, and which have left the general diet little other business than to take care of the common bailages.

That separation had another consequence, which merits attention. It produced opposite alliances with foreign powers: of Berne, at the head of the Protestant association, with the United Provinces; and of Luzerne, at the head of the Catholic association, with France.

PUBLIUS.

Here are links to my other posts on The Federalist Papers so far:

The Federalist Papers #1: Alexander Hamilton's Plea for Reasoned Debate

The Federalist Papers #3: United, the 13 States are Less Likely to Stumble into War

The Federalist Papers #4 B: National Defense Will Be Stronger if the States are United

The Federalist Papers #5: Unless United, the States Will Be at Each Others' Throats

The Federalist Papers #6 A: Alexander Hamilton on the Many Human Motives for War

The Federalist Papers #11 A: United, the States Can Get a Better Trade Deal—Alexander Hamilton

The Federalist Papers #12: Union Makes it Much Easier to Get Tariff Revenue—Alexander Hamilton

The Federalist Papers #13: Alexander Hamilton on Increasing Returns to Scale in National Government

The Federalist Papers #14: A Republic Can Be Geographically Large—James Madison

Equality of Outcome

The trouble with Thomas Sowell’s invocation of differences among siblings is that most discussions of equality of outcome are about groups to whom the law of averages should apply, rather than about individuals.

Because the gene pools for different ancestry groups are so similar, an identical environment for a long enough time should result in equality of outcome. And for those whose ancestors came to the United States centuries ago in chains, the key difference in environment was racism. Of course, one of the most powerful expressions of—and uses for—racism was slavery itself.

So for African-Americans, inequality of outcome is an indication of racism. But it points to racism operating over a long period of time, not just at, say, the latest hiring, promotion or admissions stage. My brother Chris once pointed out that many legal cases are about questions such as “Which insurance company should pay how much of the costs of this disaster?” Racism has had a huge effect on African-Americans. But whose racism? When?

Genetic data is becoming plentiful and often shows strong causal effects of genes. But one of the reasons genetic effects are so strong is because they operate throughout life. Similarly, racism (an aspect of environment) operates throughout the life of an African American, and has effects by having affected parents, grandparents and great-grandparents, as well as the social structure of African-American communities. On all the most important things, gene distributions are equal across races, but the effects of racism are not.

In most cases, it is a mistake to blame the racism of the most recent encounter for more than a sliver of the inequality of outcome we see. But racism stretching back hundreds of years can explain a lot. Many slivers create a huge burden.

That leaves the question of what to do now. It would be unfortunate if recognition of the reality of racism made anyone take less individual responsibility for what they can do to better their own condition. And some of that betterment of condition can be done collectively through demonstrations and other political action. Some of that betterment of condition is action in relation to one’s own individual life. Ultimately, more important than how the current situation arose is what to do about it now.

Related Posts:

The Cost of Variance Around a Mean of Statistically Discriminating Beliefs

On Policing: Roland Fryer, William Bratton, John Murad, Scott Thomson and the American People

How Even Liberal Whites Make Themselves Out as Victims in Discussions of Racism

Thinking about the 'Executive Order on Combating Race and Sex Stereotyping'

Econolimerick #6

“In good theory utility is ordinal.

Whenever I hear the word ‘cardinal’

I think of blue unicorns

and three fates called Norns

and insist on the word ‘pseudo-cardinal.’”

Note: there are three prominent examples of pseudo-cardinality, all in cases where additive separability is convenient:

the utility function for expected utility,

the period utility function for an additively time-separable overall utility function,

the contribution to social welfare from each individual’s welfare in an additively-separable social welfare function.

In each of these cases (even in 3, where there is interpersonal comparison going on), I consider it only pseudo-cardinality since one can do any monotonic transformation of overall utility (in these cases, the sum) without changing the preferences that are implied.

Cardinality would be if there were some way of measuring utility that was independent of looking at the choices people make. People claim that happiness data does that, but it isn’t so. (See “My Experiences with Gary Becker.”) And even if there were an independent way of measuring utility besides looking at the choices they made, why wouldn’t we be OK also with monotonic transformations of that independent way of measuring?

Don’t miss my other econolimericks:

My Pillbox

I thought it might be of some interest to report what vitamins and supplements I take each day. I doubt what I am doing is fully optimal, but weighing in the costs of trouble and expense as well as expected benefits, it represents my attempt at optimizing for myself.

I’ll leave out what I take for my own specific medical conditions: nonallergic rhinitis and nosebleeds. I’ll also focus on what I take on days I am not fasting. For what I do when fasting, see my post “Fasting Tips.”

Here is the list:

Psyllium husks (Metamucil equivalent). Here, to avoid having to consume sugar or a nonsugar sweetener with my psyllium husks, I am moving to taking it in pill form.

Fish oil. Here I am trying to get up to the 4 grams per day of EPA that Peter Attia recommends. (I can see the amount of EPA on the detailed label breakdown.) That turns out to be 6 big fish oil pills of the type I am using. But I haven’t had any problem downing that many.

Schiff Digestive Advantage Probiotic. This is the only kind I know that has the Bacillus Coagulans which is better able to survive stomach acid.

5000 IU of Vitamin D3. On the amount of Vitamin D, see “Carola Binder—Why You Should Get More Vitamin D: The Recommended Daily Allowance for Vitamin D Was Underestimated Due to Statistical Illiteracy.” On the importance of Vitamin D, also see “Getting More Vitamin D May Help You Fight Off the New Coronavirus” and “Vitamin D Seems to Help If You Have Non-Alcoholic Liver Disease.”

Lutein and Zeaxanthin (brand name “Ocuvite”), which I think of as “sunscreen for the retinas.”

Multivitamin. I am not very choosy here.

Garlic and Turmeric. I am thinking of these as at least weak antivirals. See “Eating During the Coronavirus Lockdown.”

That’s it, except for one legacy supplement: Peter Attia has persuaded me that the evidence for good effects from resveratrol are quite weak, so I won’t buy any more, but I am using the rest of the resveratrol I already own.

For annotated links to other posts on diet and health, see:

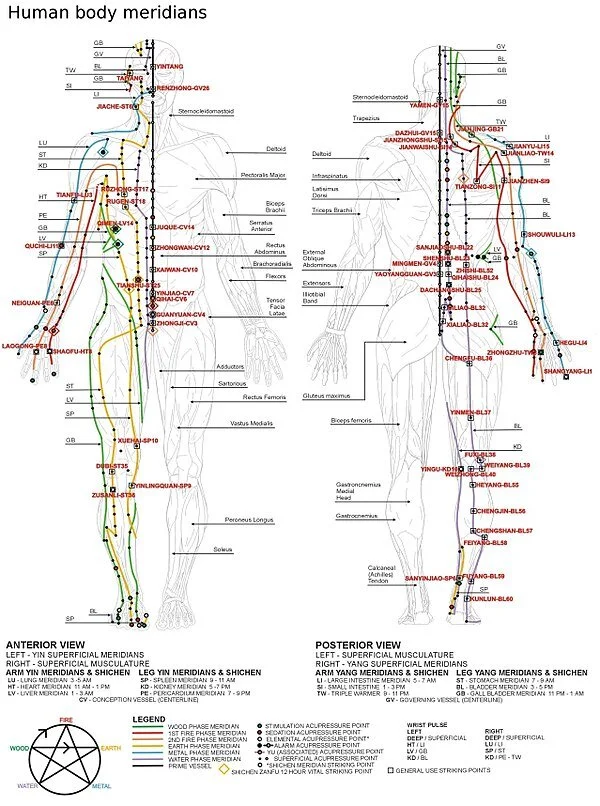

A Nonsupernaturalist Perspective on Meridians in Chinese Medicine

Link to the Wikipedia article “Meridian (Chinese Medicine)”

Certain aspects of traditional Chinese medicine have impressive empirical support. This is not surprising; there are surely some areas in which trial and error for thousands of years should be able to home in on effective procedures. (Personally, I have had acupuncture treatments. It was actually in the first year I started my blog. I was so excited by my blog that I wasn’t sleeping. I went to the acupuncturist to get help in calming down a bit. It seemed to help.)

Although important chunks of Chinese medicine pass empirical muster as effective procedures, what doesn’t pass muster is the theory of Chinese medicine: the explanation Chinese medicine gives for why Chinese medicine works. The theory of Chinese medicine involves a substance called qi—which has no counterpart in Western physics. And it involves meridians in specific places along specific paths in the body that have no counterpart in Western anatomy to the surface claims of Chinese medicine.

In “What Do You Mean by 'Supernatural'?” I use inconsistency with modern physics as my definition of “supernatural.” By that standard, Chinese medicine relies on the supernatural in explaining its own workings. Note that the inconsistency with modern physics is no small thing. If a physicist were able to detect qi and, say, incorporate it into refashioned quantum field theory, that would be truly remarkable.

But I think there is a way to rescue the meridian system, with all its specificity, while staying fully consistent with modern physics. It is well known that there are parts of the brain that are specialized for attending to sensations and initiating actions for particular parts of the body. What if the meridians are not in the body in the locations the charts say, but rather in the brain’s “map” of those parts of the body? That is, meridians might represent relatively strong neural pathways between areas of the brain that specially attend to the various points on the meridian. This might or might not be true and would need to be investigated, but it is not particularly unlikely. On this view, qi, too, is easy to understand: it is simply neural signals among different parts of the brain (which are in turn associated with different parts of the body). Neural signals are remarkable, but as far as we know, there is nothing supernatural about them.

The bottom line is:

Don’t dismiss the part of Chinese medicine based on meridians too quickly.

Don’t think that the usefulness of the part of Chinese medicine based on meridians is any reason to believe in the supernatural.

I suspect that this perspective will not seem very satisfying to most practitioners or recipients of Chinese medicine. But this perspective is, in fact, fully consistent with many of the activities of Chinese medicine.

Update, October 11, 2020, 10:22 PM: It looks like the evidence for the effectiveness of acupuncture is flimsier than I thought. See the Wikipedia article on acupuncture. It has been called a “theatrical placebo.” Of course, among placebos, theatrical ones can be especially powerful. But in particular, the evidence that using the meridians to place the needles aids effectiveness is weak. So what remains of the point of this blogpost? That even if the meridians are meaningful guides for placing acupuncture needles, it doesn’t mean there is any supernatural qi.

Related Posts:

Taking Applications for a Full-Time Research Assistantship with the Well-Being Measurement Initiative—Miles Kimball, Dan Benjamin, Ori Heffetz and Kristen Cooper

My top 4 projects in the world are to add deep negative interest rates to the monetary policy toolkit, to fight the rise of obesity and the associated chronic diseases, to enhance the scientific creativity, engagement and impact economists have, and to develop principles that put national well-being indexes on an equal footing with GDP. (On the last, see my “happiness” subblog.) Every one of these projects needs a team to help make their goal into a reality. This post is advertising an opportunity to be part of our team working out all the principles necessary to put national well-being indexes on an equal footing with GDP. The 4 professors are that team are Dan Benjamin, Ori Heffetz, Kristen Cooper and I.

I personally work very closely with our full-time research assistants. I consider many of those who have been our research assistants to be very close friends. We are looking for our next full-time research assistant for a two-year stint to begin Summer 2021, ending Summer 2023. We have two full-time research assistants overall, hiring one each year, and several part-time research assistants as well as additional coauthors on some papers we are working on. So you wouldn’t be lonely working with us!

Our research assistants working on well-being also typically hang out with other research assistants who are working on social science genetics papers with Dan Benjamin and me, and a large cast of other very interesting characters.

I have included below images of the ads for both (1) the well-being RA position and for (2) the social science genetics RA positions, and links to the ads in their original location online.

We look forward to hearing from you!

Slate Star Codex on Saturated and Polyunsaturated Fat

Why was there such a big rise in obesity in the 20th century? I would point mainly to two things: the rise in sugar content (high in almost all processed foods) and a lengthening of the eating window in the day so that people now eat almost from the moment they wake up to the moment they go to sleep at night. (See “Stop Counting Calories; It's the Clock that Counts” on why this matters.)

In the blog post “For, Then Against, High-Saturated-Fat Diets,” Slate Star Codex argues that it might be the polyunsaturated fat content of processed food (primarily vegetable oil) as much or more than the sugar content of processed food that led to the rise of obesity.

Why might polyunsaturated fat contribute to obesity? One possibility is that polyunsaturated fat might foster inflammation. That is an intriguing mechanism; focusing on reducing inflammation as a weight-loss tool sounds like a great thing to try. Now that I have said that, I’ll bet I start noticing a lot of articles and research about inflammation and weight gain and loss.

The other possibility for how polyunsaturated fat could contribute to obesity is that it has a lot of calories compared to how satiated it makes people feel. This, too, is a mechanism that would be interesting far beyond just thinking about polyunsaturated fat. I’ll bet that sugar has one of the lowest ratios of satiation to calories of food ingredients. But polyunsaturated fat could be low on this ratio.

“For, Then Against, High-Saturated-Fat Diets” discusses the claim that saturated fat has a high ratio of satiation to calories. The evidence discussed seems to suggest that one shouldn’t lump all saturated fat into one category for this: some types of saturated fat seem to have a high ratio of satiation to calories, others not so much.

I like Slate Star Codex’s focus on the question of why obesity is so much higher now than it used to be. This discussion is lacking however, by not talking about the timing of eating. (See “Stop Counting Calories; It's the Clock that Counts.”) Evidence has been accumulating that eating all the time can lead to obesity and disease and conversely that time-restricted eating can reduce obesity and disease.

But even if you believe in fasting (not eating, but drinking water) as a weight-loss tool as I do, the ratio of satiation to calories is a very interesting ratio to measure. Eating foods high on the satiation to calorie ratio for one’s last meal before fasting could make fasting easier, for example.

Let me conclude by saying where I am now in relation to different types of fat. I act on the assumption that avocados and olive oil are healthy (monounsaturated fats). I consume quite a bit of coconut milk (with one type of saturated fat) not being sure that it is healthy, but not yet seeing any big red flags in what I have read. I eat a fair amount of butter and cream. Experientially, they seem quite satiating—perhaps satiating enough to have a high satiation to calorie ratio. When it comes to meat and milk, I have other worries that have nothing to do with their saturated fat content. See “Meat Is Amazingly Nutritious—But Is It Amazingly Nutritious for Cancer Cells, Too?” and “'Is Milk Ok?' Revisited.”

Don’t miss my other recent post on this topic: “Journal of the American College of Cardiology State-of-the-Art Review on Saturated Fats.”

For annotated links to other posts on diet and health, see:

The Federalist Papers #18: Alexander Hamilton and James Madison Point to the Weakness of Confederations of Cities in Ancient Greece to Argue for a Strong Federal Government

Many of the intended audience for the Federalist Papers—had some bit of a classical education. So in the Federalist Papers #18, Alexander Hamilton and James Madison felt they could use Greek history to help make their point that a strong federal government was needed. Here is a nice statement of their argument, with its obvious application to the situation in 1787:

Had Greece, says a judicious observer on her fate, been united by a stricter confederation, and persevered in her union, she would never have worn the chains of Macedon; and might have proved a barrier to the vast projects of Rome.

Alexander Hamilton and James Madison’s conclusion to the Federalist Papers #18 echoes the Federalist Paper #17 (see “The Federalist Papers #17: Three Levels of Federal Power). They write (pretending to be a single author, “Publius”:

I have thought it not superfluous to give the outlines of this important portion of history … it emphatically illustrates the tendency of federal bodies rather to anarchy among the members, than to tyranny in the head

The full text of the Federalist Papers #18 is below for context. But let me pull out quotations referring to different ways things went badly from Greek confederations having no center or a center that could not hold. (Many of these descriptions of what happened in these Greek confederations remind me of what happens with the United Nations, which is a weak confederation indeed.)

Weak Confederations are often Dominated by the Strongest Member States

Alexander Hamilton and James Madison point out that, in lieu of being subject to a strong central government, weak confederations often leave weaker states subject to stronger states within the confederation:

The more powerful members, instead of being kept in awe and subordination, tyrannized successively over all the rest. …

It happened but too often, according to Plutarch, that the deputies of the strongest cities awed and corrupted those of the weaker; and that judgment went in favor of the most powerful party.

The smaller members, though entitled by the theory of their system to revolve in equal pride and majesty around the common center, had become, in fact, satellites of the orbs of primary magnitude.

One reason for this was that those running the confederation were entirely beholden to the governments of the member states, and therefore often acted for the interests of those states rather than for the interests of the confederation as a whole:

The powers, like those of the present Congress, were administered by deputies appointed wholly by the cities in their political capacities; and exercised over them in the same capacities.

Vulnerability to Foreign Interference and Civil War

A more serious defect of a weak confederation, or even a confederation of middling strength is that member states can easily be coopted by foreign powers. This vulnerability often arises during wars within a confederation:

Even in the midst of defensive and dangerous wars with Persia and Macedon, the members never acted in concert, and were, more or fewer of them, eternally the dupes or the hirelings of the common enemy.

After the conclusion of the war with Xerxes, it appears that the Lacedaemonians required that a number of the cities should be turned out of the confederacy for the unfaithful part they had acted. The Athenians, finding that the Lacedaemonians would lose fewer partisans by such a measure than themselves, and would become masters of the public deliberations, vigorously opposed and defeated the attempt.

Athens and Sparta, inflated with the victories and the glory they had acquired, became first rivals and then enemies.

The Phocians having ploughed up some consecrated ground belonging to the temple of Apollo, the Amphictyonic council, according to the superstition of the age, imposed a fine on the sacrilegious offenders. The Phocians, being abetted by Athens and Sparta, refused to submit to the decree. The Thebans, with others of the cities, undertook to maintain the authority of the Amphictyons, and to avenge the violated god. The latter, being the weaker party, invited the assistance of Philip of Macedon, who had secretly fostered the contest.

The arts of division were practiced among the Achaeans. Each city was seduced into a separate interest; the union was dissolved. Some of the cities fell under the tyranny of Macedonian garrisons; others under that of usurpers springing out of their own confusions. Shame and oppression erelong awaken their love of liberty. A few cities reunited. Their example was followed by others, as opportunities were found of cutting off their tyrants. The league soon embraced almost the whole Peloponnesus. Macedon saw its progress; but was hindered by internal dissensions from stopping it. All Greece caught the enthusiasm and seemed ready to unite in one confederacy, when the jealousy and envy in Sparta and Athens, of the rising glory of the Achaeans, threw a fatal damp on the enterprise. The dread of the Macedonian power induced the league to court the alliance of the Kings of Egypt and Syria, who, as successors of Alexander, were rivals of the king of Macedon. This policy was defeated by Cleomenes, king of Sparta, who was led by his ambition to make an unprovoked attack on his neighbors, the Achaeans, and who, as an enemy to Macedon, had interest enough with the Egyptian and Syrian princes to effect a breach of their engagements with the league.

The Achaeans were now reduced to the dilemma of submitting to Cleomenes, or of supplicating the aid of Macedon, its former oppressor. The latter expedient was adopted. The contests of the Greeks always afforded a pleasing opportunity to that powerful neighbor of intermeddling in their affairs.

they once more had recourse to the dangerous expedient of introducing the succor of foreign arms. The Romans, to whom the invitation was made, eagerly embraced it. Philip was conquered; Macedon subdued. A new crisis ensued to the league. Dissensions broke out among it members. These the Romans fostered.

These Defects Occurred in Confederation Stronger in Important Respects than the Strength of the Articles of Confederation

Despite the sad accounts of the fates of the two leagues of Greek cities, the Amphictyons and the Achaean League, Alexander Hamilton and James Hamilton that the Articles of Confederation left the 13 states in an even worse situation, especially because the glue of religion was stronger for the Greek cities:

In several material instances, they exceed the powers enumerated in the articles of confederation. The Amphictyons had in their hands the superstition of the times, one of the principal engines by which government was then maintained; they had a declared authority to use coercion against refractory cities, and were bound by oath to exert this authority on the necessary occasions.

The Amphictyons were the guardians of religion, and of the immense riches belonging to the temple of Delphos, where they had the right of jurisdiction in controversies between the inhabitants and those who came to consult the oracle. As a further provision for the efficacy of the federal powers, they took an oath mutually to defend and protect the united cities, to punish the violators of this oath, and to inflict vengeance on sacrilegious despoilers of the temple.

The Relative Strength of the Achaean League Suggests Benefits of the Constitution for the Quality of the Government within States

In what may be considered an aside, Alexander Hamilton and James Madison point to the benefits of even a somewhat strong union of states on the quality of government within each state:

One important fact seems to be witnessed by all the historians who take notice of Achaean affairs. It is, that as well after the renovation of the league by Aratus, as before its dissolution by the arts of Macedon, there was infinitely more of moderation and justice in the administration of its government, and less of violence and sedition in the people, than were to be found in any of the cities exercising SINGLY all the prerogatives of sovereignty. The Abbe Mably, in his observations on Greece, says that the popular government, which was so tempestuous elsewhere, caused no disorders in the members of the Achaean republic, BECAUSE IT WAS THERE TEMPERED BY THE GENERAL AUTHORITY AND LAWS OF THE CONFEDERACY.

Conclusion

I wonder what history people can be assumed to know now to serve as background for political arguments.

FEDERALIST NO. 18

The Same Subject Continued: The Insufficiency of the Present Confederation to Preserve the Union

For the Independent Journal.

Author: Alexander Hamilton and James Madison

To the People of the State of New York:

AMONG the confederacies of antiquity, the most considerable was that of the Grecian republics, associated under the Amphictyonic council. From the best accounts transmitted of this celebrated institution, it bore a very instructive analogy to the present Confederation of the American States.

The members retained the character of independent and sovereign states, and had equal votes in the federal council. This council had a general authority to propose and resolve whatever it judged necessary for the common welfare of Greece; to declare and carry on war; to decide, in the last resort, all controversies between the members; to fine the aggressing party; to employ the whole force of the confederacy against the disobedient; to admit new members. The Amphictyons were the guardians of religion, and of the immense riches belonging to the temple of Delphos, where they had the right of jurisdiction in controversies between the inhabitants and those who came to consult the oracle. As a further provision for the efficacy of the federal powers, they took an oath mutually to defend and protect the united cities, to punish the violators of this oath, and to inflict vengeance on sacrilegious despoilers of the temple.

In theory, and upon paper, this apparatus of powers seems amply sufficient for all general purposes. In several material instances, they exceed the powers enumerated in the articles of confederation. The Amphictyons had in their hands the superstition of the times, one of the principal engines by which government was then maintained; they had a declared authority to use coercion against refractory cities, and were bound by oath to exert this authority on the necessary occasions.

Very different, nevertheless, was the experiment from the theory. The powers, like those of the present Congress, were administered by deputies appointed wholly by the cities in their political capacities; and exercised over them in the same capacities. Hence the weakness, the disorders, and finally the destruction of the confederacy. The more powerful members, instead of being kept in awe and subordination, tyrannized successively over all the rest. Athens, as we learn from Demosthenes, was the arbiter of Greece seventy-three years. The Lacedaemonians next governed it twenty-nine years; at a subsequent period, after the battle of Leuctra, the Thebans had their turn of domination.

It happened but too often, according to Plutarch, that the deputies of the strongest cities awed and corrupted those of the weaker; and that judgment went in favor of the most powerful party.

Even in the midst of defensive and dangerous wars with Persia and Macedon, the members never acted in concert, and were, more or fewer of them, eternally the dupes or the hirelings of the common enemy. The intervals of foreign war were filled up by domestic vicissitudes convulsions, and carnage.

After the conclusion of the war with Xerxes, it appears that the Lacedaemonians required that a number of the cities should be turned out of the confederacy for the unfaithful part they had acted. The Athenians, finding that the Lacedaemonians would lose fewer partisans by such a measure than themselves, and would become masters of the public deliberations, vigorously opposed and defeated the attempt. This piece of history proves at once the inefficiency of the union, the ambition and jealousy of its most powerful members, and the dependent and degraded condition of the rest. The smaller members, though entitled by the theory of their system to revolve in equal pride and majesty around the common center, had become, in fact, satellites of the orbs of primary magnitude.

Had the Greeks, says the Abbe Milot, been as wise as they were courageous, they would have been admonished by experience of the necessity of a closer union, and would have availed themselves of the peace which followed their success against the Persian arms, to establish such a reformation. Instead of this obvious policy, Athens and Sparta, inflated with the victories and the glory they had acquired, became first rivals and then enemies; and did each other infinitely more mischief than they had suffered from Xerxes. Their mutual jealousies, fears, hatreds, and injuries ended in the celebrated Peloponnesian war; which itself ended in the ruin and slavery of the Athenians who had begun it.

As a weak government, when not at war, is ever agitated by internal dissentions, so these never fail to bring on fresh calamities from abroad. The Phocians having ploughed up some consecrated ground belonging to the temple of Apollo, the Amphictyonic council, according to the superstition of the age, imposed a fine on the sacrilegious offenders. The Phocians, being abetted by Athens and Sparta, refused to submit to the decree. The Thebans, with others of the cities, undertook to maintain the authority of the Amphictyons, and to avenge the violated god. The latter, being the weaker party, invited the assistance of Philip of Macedon, who had secretly fostered the contest. Philip gladly seized the opportunity of executing the designs he had long planned against the liberties of Greece. By his intrigues and bribes he won over to his interests the popular leaders of several cities; by their influence and votes, gained admission into the Amphictyonic council; and by his arts and his arms, made himself master of the confederacy.

Such were the consequences of the fallacious principle on which this interesting establishment was founded. Had Greece, says a judicious observer on her fate, been united by a stricter confederation, and persevered in her union, she would never have worn the chains of Macedon; and might have proved a barrier to the vast projects of Rome.

The Achaean league, as it is called, was another society of Grecian republics, which supplies us with valuable instruction.

The Union here was far more intimate, and its organization much wiser, than in the preceding instance. It will accordingly appear, that though not exempt from a similar catastrophe, it by no means equally deserved it.

The cities composing this league retained their municipal jurisdiction, appointed their own officers, and enjoyed a perfect equality. The senate, in which they were represented, had the sole and exclusive right of peace and war; of sending and receiving ambassadors; of entering into treaties and alliances; of appointing a chief magistrate or praetor, as he was called, who commanded their armies, and who, with the advice and consent of ten of the senators, not only administered the government in the recess of the senate, but had a great share in its deliberations, when assembled. According to the primitive constitution, there were two praetors associated in the administration; but on trial a single one was preferred.

It appears that the cities had all the same laws and customs, the same weights and measures, and the same money. But how far this effect proceeded from the authority of the federal council is left in uncertainty. It is said only that the cities were in a manner compelled to receive the same laws and usages. When Lacedaemon was brought into the league by Philopoemen, it was attended with an abolition of the institutions and laws of Lycurgus, and an adoption of those of the Achaeans. The Amphictyonic confederacy, of which she had been a member, left her in the full exercise of her government and her legislation. This circumstance alone proves a very material difference in the genius of the two systems.

It is much to be regretted that such imperfect monuments remain of this curious political fabric. Could its interior structure and regular operation be ascertained, it is probable that more light would be thrown by it on the science of federal government, than by any of the like experiments with which we are acquainted.

One important fact seems to be witnessed by all the historians who take notice of Achaean affairs. It is, that as well after the renovation of the league by Aratus, as before its dissolution by the arts of Macedon, there was infinitely more of moderation and justice in the administration of its government, and less of violence and sedition in the people, than were to be found in any of the cities exercising SINGLY all the prerogatives of sovereignty. The Abbe Mably, in his observations on Greece, says that the popular government, which was so tempestuous elsewhere, caused no disorders in the members of the Achaean republic, BECAUSE IT WAS THERE TEMPERED BY THE GENERAL AUTHORITY AND LAWS OF THE CONFEDERACY.

We are not to conclude too hastily, however, that faction did not, in a certain degree, agitate the particular cities; much less that a due subordination and harmony reigned in the general system. The contrary is sufficiently displayed in the vicissitudes and fate of the republic.

Whilst the Amphictyonic confederacy remained, that of the Achaeans, which comprehended the less important cities only, made little figure on the theatre of Greece. When the former became a victim to Macedon, the latter was spared by the policy of Philip and Alexander. Under the successors of these princes, however, a different policy prevailed. The arts of division were practiced among the Achaeans. Each city was seduced into a separate interest; the union was dissolved. Some of the cities fell under the tyranny of Macedonian garrisons; others under that of usurpers springing out of their own confusions. Shame and oppression erelong awaken their love of liberty. A few cities reunited. Their example was followed by others, as opportunities were found of cutting off their tyrants. The league soon embraced almost the whole Peloponnesus. Macedon saw its progress; but was hindered by internal dissensions from stopping it. All Greece caught the enthusiasm and seemed ready to unite in one confederacy, when the jealousy and envy in Sparta and Athens, of the rising glory of the Achaeans, threw a fatal damp on the enterprise. The dread of the Macedonian power induced the league to court the alliance of the Kings of Egypt and Syria, who, as successors of Alexander, were rivals of the king of Macedon. This policy was defeated by Cleomenes, king of Sparta, who was led by his ambition to make an unprovoked attack on his neighbors, the Achaeans, and who, as an enemy to Macedon, had interest enough with the Egyptian and Syrian princes to effect a breach of their engagements with the league.

The Achaeans were now reduced to the dilemma of submitting to Cleomenes, or of supplicating the aid of Macedon, its former oppressor. The latter expedient was adopted. The contests of the Greeks always afforded a pleasing opportunity to that powerful neighbor of intermeddling in their affairs. A Macedonian army quickly appeared. Cleomenes was vanquished. The Achaeans soon experienced, as often happens, that a victorious and powerful ally is but another name for a master. All that their most abject compliances could obtain from him was a toleration of the exercise of their laws. Philip, who was now on the throne of Macedon, soon provoked by his tyrannies, fresh combinations among the Greeks. The Achaeans, though weakenened by internal dissensions and by the revolt of Messene, one of its members, being joined by the AEtolians and Athenians, erected the standard of opposition. Finding themselves, though thus supported, unequal to the undertaking, they once more had recourse to the dangerous expedient of introducing the succor of foreign arms. The Romans, to whom the invitation was made, eagerly embraced it. Philip was conquered; Macedon subdued. A new crisis ensued to the league. Dissensions broke out among it members. These the Romans fostered. Callicrates and other popular leaders became mercenary instruments for inveigling their countrymen. The more effectually to nourish discord and disorder the Romans had, to the astonishment of those who confided in their sincerity, already proclaimed universal liberty [This was but another name more specious for the independence of the members on the federal head.] throughout Greece. With the same insidious views, they now seduced the members from the league, by representing to their pride the violation it committed on their sovereignty. By these arts this union, the last hope of Greece, the last hope of ancient liberty, was torn into pieces; and such imbecility and distraction introduced, that the arms of Rome found little difficulty in completing the ruin which their arts had commenced. The Achaeans were cut to pieces, and Achaia loaded with chains, under which it is groaning at this hour.

I have thought it not superfluous to give the outlines of this important portion of history; both because it teaches more than one lesson, and because, as a supplement to the outlines of the Achaean constitution, it emphatically illustrates the tendency of federal bodies rather to anarchy among the members, than to tyranny in the head

PUBLIUS.

Here are links to my other posts on The Federalist Papers so far:

The Federalist Papers #1: Alexander Hamilton's Plea for Reasoned Debate

The Federalist Papers #3: United, the 13 States are Less Likely to Stumble into War

The Federalist Papers #4 B: National Defense Will Be Stronger if the States are United

The Federalist Papers #5: Unless United, the States Will Be at Each Others' Throats

The Federalist Papers #6 A: Alexander Hamilton on the Many Human Motives for War

The Federalist Papers #11 A: United, the States Can Get a Better Trade Deal—Alexander Hamilton

The Federalist Papers #12: Union Makes it Much Easier to Get Tariff Revenue—Alexander Hamilton

The Federalist Papers #13: Alexander Hamilton on Increasing Returns to Scale in National Government

The Federalist Papers #14: A Republic Can Be Geographically Large—James Madison