Donald Trump May Finally Get People to Realize the Fed is Responsible for What Happens with the Business Cycle, Not the President or Congress

Throughout my career as a macroeconomics professor (now 32 years since my PhD), I have been dismayed by the lack of understanding that it is the Fed, not the President of the United States or Congress that should be blamed and praised for recessions and recoveries. Occasionally, the Fed doesn’t do its job well, and actions of the President of the United States and Congress can help, as when Barack Obama got through congress a stimulus bill during the Great Recession. And, of course, the Fed’s existence, independence and some aspects of its toolkit depend on Congressional authorization. But as long as the Fed is given the power it needs to tame the business cycle (see “How and Why to Eliminate the Zero Lower Bound: A Reader’s Guide”), it is the Fed that should be held accountable for the business cycle.

There are three big problems with what until very recently was the political reality that the President faced the electoral consequences of the business cycle, even though dealing with the business cycle is the Fed’s responsibility (a responsibility for which it has been given great power and independence).

First, inappropriately given the President of the United States credit or blame for the business cycle diverts attention from judging how a president is doing in dealing with long-run economic issues, foreign-policy issues, cultural issues and in setting a good example of personal behavior for the nation.

Second, even if people also paid attention to all those other dimensions of presidential performance, giving the president credit or blame for the current state of the business cycle adds a lot of random noise to evaluations of the president.

Third, giving credit or blame to the president makes it too easy for the Fed to duck responsibility. It pains me to hear the Fed or any central bank call for fiscal stimulus as a way to duck responsibility for cutting interest rates as much as necessary to stabilize the economy. I recognize that needed interest rate cuts, like needed interest rate hikes, often subject the Fed and other central banks to a lot of criticism. But just as you shouldn’t accept an appointment to the Federal Reserve Board or to be President of one of the regional Federal Reserve Banks if you can’t stand the heat that comes from raising interest rates if necessary to head off excessive inflation, you shouldn’t accept an appointment to the Federal Reserve Board or to be President of one of the regional Federal Reserve Banks if you can’t stand the heat that comes from cutting interest rates—even to negative rates if necessary—if that is what is required to get speedy economic recovery.

There is now hope—from an unexpected source—that the American public will begin to understand that it is the Fed, not the President or Congress, that is responsible for the business cycle. Donald Trump’s frequent criticism of the Fed, while often misguided, does put responsibility for the business cycle in the Fed’s lap. Of course, Donald Trump is not 100% consistent in this. If the business cycle situation looks good, he wants to take credit; if the business cycle situation looks bad, he wants to shift the blame to the Fed. Overall, however, Donald Trump has been more vocal in shifting the onus of managing the business cycle from the President of the United States to the Fed than any other president since the founding of the Fed.

As I have emphasized many times, monetary policy is limited in its power. It can tame the business cycle. But it can’t do much about long-run economic growth or the long-run interest rate, let alone solve all the many problems we face—such as the rise in obesity or nuclear proliferation—that don’t show up directly in GDP.

Even to tame the business cycle, the Fed does need support from the president and Congress.

First, the Fed needs an extensive toolkit that includes being able to use negative rates and to modify paper currency policy as necessary to accommodate negative rates. (Again, see “How and Why to Eliminate the Zero Lower Bound: A Reader’s Guide.”) It is an interesting and nonobvious legal question (which I am teaming up with a law professor to try to answer) if the Fed already has this power or not. If it does already have the power to use negative rates and modify paper currency policy, then support for the Fed’s ability to tame the business cycle would involve not passing legislation to take that power away.

Second, the Fed needs appointees who understand how to use interest rates to tame the business cycle. Here, Donald Trump falls short. He has made some good nominations for the Fed, but quite a few bad suggestions of people to nominate for the Fed (some only as trial balloons without a formal nomination). Fortunately, there is hope that the Senate will do its job of putting a reasonably high floor under the quality of appointments to the Fed.

Although monetary policy could be greatly improved compared to current practice—see “Next Generation Monetary Policy”—it is my view that it has, indeed, improved over time. In that view, I include the 2008-2016 period in which monetary policy outcomes were quite bad, but the Fed and other central banks were innovating rapidly under trying circumstances.

The bar is higher for the future, however. The Fed, like other central banks, now has a playbook for getting as much monetary stimulus as necessary in any future recession in three papers I have been involved in, plus related papers by others. Here are my three:

My IMF Working Paper with Ruchir Agarwal: “Enabling Deep Negative Rates to Fight Recessions: A Guide” (pdf) (or on IMF website)

My IMF Working Paper with Ruchir Agarwal: “Breaking Through the Zero Lower Bound” (pdf) (or on IMF website)

We do the Fed and other central banks no favors by ever letting them off the hook for their job of keeping inflation steady at a carefully chosen target rate and keeping output and employment at the natural level. We deserve courage and excellence in monetary policy. Everyone who has a hand in monetary policy decision-making should feel that responsibility keenly. They are collectively blameworthy if they don’t deliver (though individuals involved in that decision-making who were overruled might in some cases be heroes even if collectively monetary policy makers failed us).

Stephen Williamson and Miles Kimball Debate the Existence of a Phillips Curve →

Also, don’t miss these interwoven threads:

Maintaining Weight Loss

I write in “3 Achievable Resolutions for Weight Loss” and “4 Propositions on Weight Loss” on how to get started with losing weight.

3 Achievable Resolutions for Weight Loss:

Go Off Sugar

Choose and Keep To an Eating Window Shorter than 16 Hours a Day—With Appropriate Exceptions

Come Up with an Inspirational and Informative Reading Program to Help with Weight Loss

Note: my annotated blog bibliography “Miles Kimball on Diet and Health: A Reader's Guide” may help in making this blog a useful part of your reading program on weight loss.

4 Propositions on Weight Loss:

Eating nothing leads to weight loss.

For healthy, nonpregnant, nonanorexic adults who find it relatively easy, fasting for up to 48 hours is not dangerous—as long as the dosage of any medication they are taking is adjusted for the fact that they are fasting.

Eating sugar, bread, rice and potatoes makes most people feel hungry a couple of hours later. People who have, by and large, quit eating sugar, bread, rice and potatoes can notice this effect on the rare occasions that they do eat a substantial amount of sugar, bread, rice or potatoes. Moreover, if they pay attention, those who have quit eating sugar, bread, rice and potatoes can notice which other foods cause them to feel hungry a couple of hours later.

Two months or so after quitting eating sugar, bread, rice, potatoes—and all the other foods and beverages that make them feel hungry a couple of hours later—a large fraction of people will then find fasting relatively easy.

Keeping the Weight Off

But what about when you succeed at losing weight? How can you keep the weight off? Here is my answer, in three sections:

Make sure you lose the weight as painlessly as possible in the first place

Realize that your body can now get by on much less food than you ever imagined possible

Fast however much you need to in order to keep your weight steady

A. Make sure you lose the weight as painlessly as possible in the first place

The current incarnation of the Wikipedia article “Yo-yo effect” gives this mechanism for people who diet, lose weight, but then bounce back up to a higher weight:

The reasons for yo-yo dieting are varied but often include embarking upon a hypocaloric diet that was initially too extreme. At first the dieter may experience elation at the thought of weight loss and pride in their rejection of food. Over time, however, the limits imposed by such extreme diets cause effects such as depression or fatigue that make the diet impossible to sustain. Ultimately, the dieter reverts to their old eating habits, now with the added emotional effects of failing to lose weight by restrictive diet. Such an emotional state leads many people to eating more than they would have before dieting, causing them to rapidly regain weight.

I want to take issue with the words “too extreme.” It is not the extremity of a diet as judged by someone else that matters here, but the amount of pain a dieter suffers that matters. If you experience a lot of physical suffering from a diet you are (a) probably following a physically harmful diet and (b) setting yourself up for weight gain later on because of the backlog of feelings of deprivation you will have built up. By “physical suffering,” I mean the starvation response. There are two ways to get thrown into the starvation response. One is to have almost no body fat to fall back on. (I touch on anorexia in “Don't Tar Fasting by those of Normal or High Weight with the Brush of Anorexia.”) The other is to have high insulin levels that lock fat in your fat cells, so that your cells feel starved, even though you have plenty of body fat. (This can be a matter of degree: presumably there are intermediate insulin levels at which some body fat is burned to nourish your body, but less than would ideally be called for.)

Either way, serious physical suffering during a diet is a bad sign. I’m not talking about (i) withdrawal pangs from going off sugar (which are normal), (ii) the discomfort when your body is shifting over from metabolizing the nutrients in what you usually eat to metabolizing your own body fat (which you might feel during the first day or so of fasting) or (iii) yearnings for particular foods or food in general because food can be so delicious and fun (or because you saw, smelled or were reminded of food by someone else). I’m talking about feeling starved—which can happen as soon as a few hours after eating something very high on the insulin index. (See “Forget Calorie Counting; It's the Insulin Index, Stupid.”)

The bottom line is this: don’t try to diet without giving up sugar and other foods high on the insulin index. If you do, your diet is likely to be a hellish experience, and you may have a psychological backlash that undoes your dieting efforts and more.

(Can you occasionally cheat? People differ in how well that works for them psychologically. And cheating with a very, very small quantity is obviously not the same as going whole hog. But my advice is to go cold turkey in giving up sugar—and potatoes, rice and bread—for a long time and only allow small amounts of cheating when you are deep into the maintenance phase. And if you do ever cheat, notice carefully and honestly what the effects are. Do you feel hungrier in the next 24 hours after you cheated? My prediction is that having an entire “cheat day” once a week as I have heard some people advocate is going to make your diet much more miserable than if you don’t do a cheat day.)

Making weight loss as painless as possible is likely to be so important to avoiding a yo-yo bounceback in your weight that, even if your current diet seems to be working well when you look at the scale, I recommend that you switch immediately to a low-insulin-index diet, starting by giving up sugar.

B. Realize that your body can now get by on much less food than you ever imagined possible

I am very critical of calorie-counting as an entry-point into weight loss: see “Obesity Is Always and Everywhere an Insulin Phenomenon” and “Forget Calorie Counting; It's the Insulin Index, Stupid.” But an awareness of calories can play a useful role after you have lost weight in helping you maintain weight loss. Here is how I put it in “How Low Insulin Opens a Way to Escape Dieting Hell” (emphasis added):

Once you have your insulin levels low enough through switching to low-insulin-index foods and having big chunks of time with no food at all, your body will be open to the possibility of burning body fat. Then and only then will you get the results people naively think they will get based on the usual calories in/calories out logic. But what you will find is that with your body open to the possibility of burning body fat, you won’t suffer from having substantial chunks of time with no food and having your total calorie intake from the outside world low. The reason is that a calorie from burning your own fat is just as good as a calorie from food you are eating now in keeping you well nourished and feeling good.

…

… weight-loss efforts that lack the key element of keeping your insulin levels low are likely to fail, and cause you a lot of misery on the road to failure as well as the disappointment of failure as the destination. If you do what it takes to keep your insulin levels low, people might well say “Of course that worked! You were avoiding sugar, refined carbohydrates and processed food, and going substantial chunks of time without eating!” But if they keep to the conventional wisdom that only focuses on calories-in/calories-out (and in the usual approach, inevitably ignoring many subtleties even about the calories out and about the detailed genesis of temptations for calories in), they won’t have as good an explanation for why what other people try doesn’t work in the long run.

Let me give some examples of how some awareness of calories is helpful, as long as you are doing everything else right first:

True nuts are very healthy. See “Our Delusions about 'Healthy' Snacks—Nuts to That!” You shouldn’t get food cravings after eating true nuts in the way you would after eating sugar. But nuts also don’t seem to generate a strong satiation signal. It is relatively easy to keep eating more and more simply because they are delicious, even without the type of cravings one would get from less healthy food.

Cream, by contrast, is quite satiating. So, unless you are pushing yourself to feeling overfull (a genuine issue) having cream as part of your meals is, in my view, fine. Cream can also be, say, used in tea or coffee on a fasting day without jacking up your insulin and therefore without making you hungry. But I have been wondering if the amount of cream I have consumed on many fasting days provided enough calories to seriously blunt my weight loss from those days. I worry that milk would jack up insulin more than cream, so what I am trying to do is reduce the amount of cream I use in tea or coffee, and more often go without any cream.

It is a hotly debated question, but there is some evidence that low-carb eating can rev up calorie-burning. (I suspect it is really low-insulin-index eating doing the trick. See “Why a Low-Insulin-Index Diet Isn't Exactly a 'Lowcarb' Diet.”) If you want to delve into that debate, see:

Framingham State Food Study: Lowcarb Diets Make Us Burn More Calories

Layne Norton Discusses the Stephan Guyenet vs. Gary Taubes Debate (a Debate on Joe Rogan’s Podcast)

David Ludwig: It Takes Time to Adapt to a Lowcarb, Highfat Diet

On the Epistemology of Diet and Health: Miles Refuses to `Stay in His Lane’

However, even if low-insulin-index eating by itself revs up calorie-burning, losing weight leads to less calorie burning. See “Kevin D. Hall and Juen Guo: Why it is so Hard to Lose Weight and so Hard to Keep it Off.” Over time, when your body sees less food coming in, it gets more efficient at metabolizing the food that does come in. So you need fewer calories to keep your body going vigorously than you used before. The bottom line is that you need to adjust your expectations for what is a normal amount to eat. After losing weight, you are likely to find that you can eat remarkably little in total without suffering physically and without losing any more weight.

Many people see their body getting more efficient at getting by on relatively little food as an unmitigated curse. I see it differently. The less food my healthy cells are getting by on, the less food there is to help any cancer cells or precancer cells in my body to thrive. Since cancer cells tend to be metabolically damaged, they are likely to do badly in competition with healthy cells if food availability inside my body is limited. (And the nutrients that come from body fat being metabolized are not the ideal food for metabolically handicapped cancer cells.) On this way of thinking about the relationship between getting by vigorously with only a little food and cancer, see:

C. Fast however much you need to in order to keep your weight steady

Fasting—having periods of time during which you don’t eat, but drink water, tea and coffee—doesn’t need to be on any regular schedule. But you will need to do a certain total amount of fasting to keep your weight steady—and even more if you still want to lose more weight. (Note: I discuss modified fasting in “Forget Calorie Counting; It's the Insulin Index, Stupid.” Modified fasting has a somewhat muted effect from having some calorie intake, but it works too. You will just need to do somewhat more of it than if you were doing full-out fasting.)

I am a strong advocate of the idea that, to keep a pattern of eating sustainable, it is important to accommodate social occasions in which people eat together. (It is usually possible to find low-insulin-index food to eat at most restaurants and in most banquets or spreads.) Personally, I have enough social occasions involving food that I participate in, and my body has become efficient enough getting by with relatively little food, that it takes a lot of fasting to keep my weight even. But, as I have emphasized in my whole run of diet and health posts, fasting is not painful for me. And I think that for most adults, after they have adapted to a low-insulin-index diet, there exists for them some form of modified fast that will not be painful, yet will have a strongly negative energy balance that can neutralize the effect of other days that have a positive energy balance.

The key is to alternate fasting with feasting. The more feasting you do, the more fasting you will need to do. But as long as you eat low on the insulin index, and modify your fasts (within the parameters of what I talk about in “Forget Calorie Counting; It's the Insulin Index, Stupid”) according to what works for you, personally, the alternation between feasting and fasting should go smoothly.

It is worth giving one simple example of a modified fast. If you can be strict during the rest of the day, but are a light enough sleeper so that even a modest amount of hunger can interfere with falling asleep, on a day you are fasting you may want to plan on eating a quarter cup of macadamia nuts and maybe a cup of tea with cream before bed.

Figure out the minimum quantity of very-low-insulin-index food you need to eat on a day you are fasting in order to keep things reasonably pleasant. The more calories worth of very-low-insulin-index food you eat on a day of modified fasting, the more days of modified fasting you will need to do to keep your weight even, but on the other hand, those days may be enough more pleasant that more of them is a good tradeoff.

You can also tradeoff the amount of you eat on a typical day of modified fasting and number of modified fasting days against how much you feast on low-insulin-index food on eating days. My advice is that, psychologically, it is very valuable to have days when you feel like you are feasting. Don’t hold back too much! Your gustatory life will be quite drab otherwise. But there may be some sacrifice you can make on an eating day that is not much of a sacrifice at all.

Ultimately, how much fasting or modified fasting you will need to do is an empirical matter. It is what it is. You might not like the findings from your experiments in how much fasting or modified fasting it takes to keep your weight steady given your patterns of eating on eating days and your mode of modified fasting. But that’s the way it is. My claim is that if you are eating low on the insulin index that you will be able to fast or do modified fasting enough to do the trick without any of the true suffering that dieters using other techniques so commonly experience.

The amount of fasting of modified fasting you need to maintain your weight loss may require a fair amount of self-discipline. You may need to exercise some creativity to figure out a form of modified fasting that works for you. You may need to exercise some creativity to make sure that your feasting is fun enough that you can see your way through to continuing what you are doing of something like it for the rest of your life. But the rewards are great: not just weight loss, but better health on many dimensions. By the time you reach my age—now 58—you’ll realize how precious good health is. People say “Time is money.” Here I am saying “Health is time.” And time is much more than money—it is a key input to almost everything you want.

For annotated links to other posts on diet and health, see “Miles Kimball on Diet and Health: A Reader's Guide.”

On the Effability of the Ineffable

Ineffable: Beyond expression; indescribable or unspeakable.

There is a paradox in the use of the word “ineffable”: by saying that something cannot be described, the word “ineffable” often points to a common human experience—and thereby communicates. And this is not so different from ordinary words. Many ordinary words are only understandable because of the common human experience and common human nature that we share. (That is the theme of my Linguistics Master’s Thesis. See “Miles's Linguistics Master's Thesis: The Later Wittgenstein, Roman Jakobson and Charles Saunders Peirce.”) Similarly, things that are called “ineffable,” like the pleasure of a sunset, or a mystical experience in a religious context that regularly produces such mystical experiences in coreligionists, or consciousness, are understandable to the many people who share those experiences due to their human nature. (Don’t miss my sermon “The Mystery of Consciousness.”)

One of the big jobs of the Humanities is precisely to express what had previously been ineffable—to be able to point to or evoke feelings and thereby given them a name, even if the name is the length of a novel.

The subject matter of the Humanities is also reachable by science. If anything can be expressed in words or in a painting or in music, then multimedia surveys can ask about it. And once a survey can ask about it, it can be quantified. A good thing, too! Because continuing to improve human welfare at some point involves helping people grab hold of more of the wondrous intangible things that they want. I am proud to be heavily involved in research in the economics of happiness—which is really not just about happiness alone, but about all the wondrous and the quotidian, intangible and tangible things people want.

Other Related Posts:

Brent Cebul: Supply-Side Liberalism: Fiscal Crisis, Post-Industrial Policy, and the Rise of the New Democrats →

This has relatively little to do with my brand of “Supply-Side Liberalism,” but given the coincidence of the name, I thought I would post the link in case someone is interested. Here is the abstract:

A new generation of liberals emerged in the 1970s, a decade of stagflation, deindustrialization, global capital flight, and public sector fiscal crises. Prevailing interpretations of New Democrats like Bill Clinton and Michael Dukakis explain their emphasis on entrepreneurialism and post-industrial sectors as the byproduct of cynical electoral strategies of “triangulation,” that is, primarily as a reaction to the rise of Reagan Republicanism. This article instead positions their political economy as part of a much longer history of liberals’ efforts to restructure the economy in order to stimulate new jobs and tax revenues that might also generate public revenue and support a progressive policy agenda. With roots in local, state, and regional industrial policies inspired by the New Deal, “supply-side liberalism” reemerged with force in the 1970s and 1980s, revealing heretofore unappreciated continuities that contextualize and clarify the origins of New Democrats’ promotion of a set of seemingly “neoliberal” economic policies.

Against the Gold Standard

On Twitter, for the most part, the only people who talk about the gold standard are those who are in favor of it. In addition to those who mention the gold standard explicitly, anyone who says that the free market should be setting the interest rate even in the short run, with no intervention of a central bank, have to be either talking about a commodity money system—I think. I think a commodity money system would be a huge mistake, but like the sound of “the free market setting rates.” So I would be very interested in hearing about any scheme to have the free market set interest rates even in the short run that did not involve a commodity money system. (Note that cryptocurrency does not avoid having a central bank. The bitcoin algorithm is, in effect, a central bank for bitcoin. Bitcoin has a robot central bank.)

I have been a foe of the gold standard most of my life: ever since I had any opinion on the gold standard at all. The basic problem with the gold standard is the problem of instruments and targets. With the interest rate and money supply combined, we can target one thing. Should that one thing really be the price of gold? Wouldn’t we rather have it be the price of the basket of commodities in the consumer price index, say? And with price adjustment being so slow, do we really want to totally dismiss the idea of keeping output and employment at the natural level? And given the (approximately true) “Divine Coincidence” that keeping output and employment at the natural level keeps inflation steady at any chosen inflation rate, wouldn’t we want to have output and employment at the natural level and inflation equal to zero—absolute price stability? You can’t have absolute price stability and have a gold standard! The price of gold will always fluctuate relative to the basket of goods for the consumer price index.

Many supporters of the gold standard believe that central banks are inherently inflationary. That is certainly true for some central banks, but a large number of central banks now have anti-inflationary attitudes written deep into their DNA. In her July 28, 2019 Politico article “Trump Fed pick’s push for gold troubles lawmakers,” Victoria Guida says it well:

While even [Donald Trump’s intended Fed nominee Judy] Shelton agrees that the U.S. is nowhere near being on track to returning to a gold standard, which was fully abandoned by President Richard Nixon in 1971, the idea has maintained popularity in certain conservative and libertarian circles as a way to increase the dollar’s stability.

That's particularly true among those with a strong distrust of the Fed — a camp that includes Shelton.

While both the 2012 and 2016 Republican Party platforms called for a new commission to consider fixing the dollar’s value to a precious metal, most economists argue that returning to gold would prevent the central bank from acting in the best interest of the economy. They also say it would attempt to aggressively head off a problem that hasn’t existed for decades: runaway inflation.

Obsessing about a supposed strong inflationary bias on the part of major central banks is fighting monetary policy’s last war: defeating the Great Inflation of the 1970s. The current monetary policy war we are in is a war against the threat of deflation or a recurrence of the Great Recession. And there are many other future battles to fight in monetary policy, including getting a monetary policy framework that can make it safe to have zero inflation instead of 2%-4% per year. (See “The Costs and Benefits of Repealing the Zero Lower Bound...and Then Lowering the Long-Run Inflation Target” and “Next Generation Monetary Policy.”)

Quotations from interviews and other reporting Victoria does in “Trump Fed pick’s push for gold troubles lawmakers” are worth repeating:

The gold standard would probably shatter a lot of people’s dreams around the world right now. … There was a reason to get off of it.” —Senator Richard Shelby (R-Ala.), a key member of the Banking Committee

Support for tying the dollar to gold's value makes a Fed candidate “manifestly unqualified, in the same way I wouldn’t have a surgeon general who supported leeches and bloodletting,” said Jason Furman, a Harvard professor and former chief economist to President Barack Obama. “It handcuffs the Fed and locks them into focusing on an objective that has no underlying reality, which is the price of the dollar relative to gold.”

“I don’t think it’s relevant,” Sen. Tim Scott (R-S.C.) said when asked about her views on gold, adding that there was no need to focus on “controversial statements” [that Judy Shelton made about the gold standard]

George Selgin, an economist at Cato, is sympathetic to the goals of gold standard supporters but doesn’t agree with their solution.

In 2012, the University of Chicago’s Booth School of Business asked 40 prominent economists whether a return to the gold standard would be better for the average American. All of them said no.

Once upon a time, a commodity standard for money was better than what preceded it. That time is long past. Today, the gold standard is a bad idea that deserves its place in history—not a place in the present. Back in the 1930s, weakening the gold standard was the most important economic policy move Franklin Delano Roosevelt did in order to get the United States out of the Great Depression. By handcuffing monetary policy, the gold standard was a bad idea during the Great Depression, and would be a bad idea now, likely to bring a return to a new depression if not quickly abandoned.

Other links about the gold standard:

Did the Gold Standard Help Bring Hitler to Power? (Twitter Round Table)

Matthew O'Brien versus the Gold Standard

Stephen Cechetti and Kermit Schoenholtz: Why a Gold Standard is Bad

Additional links about “gold”:

Tim Harford: It’s Tough Turning Ideas into Gold

xkcd Webcomic on the Pot of Gold at the End of the Rainbow

Gold, Electronic Money, and the Determinants of the Prices of Storable Commodities from the Ground

Links about cryptocurrency:

Governments Can and Should Beat Bitcoin at Its Own Game

What Bitcoin Tells Us about Electronic Money

Susan Athey on Bitcoin as a Medium of Exchange

Cryptocurrency Conference Tweets

Diego Espinosa and Miles Kimball on Bitcoin and Electronic Money

Reexamining Steve Gundry's `The Plant Paradox’

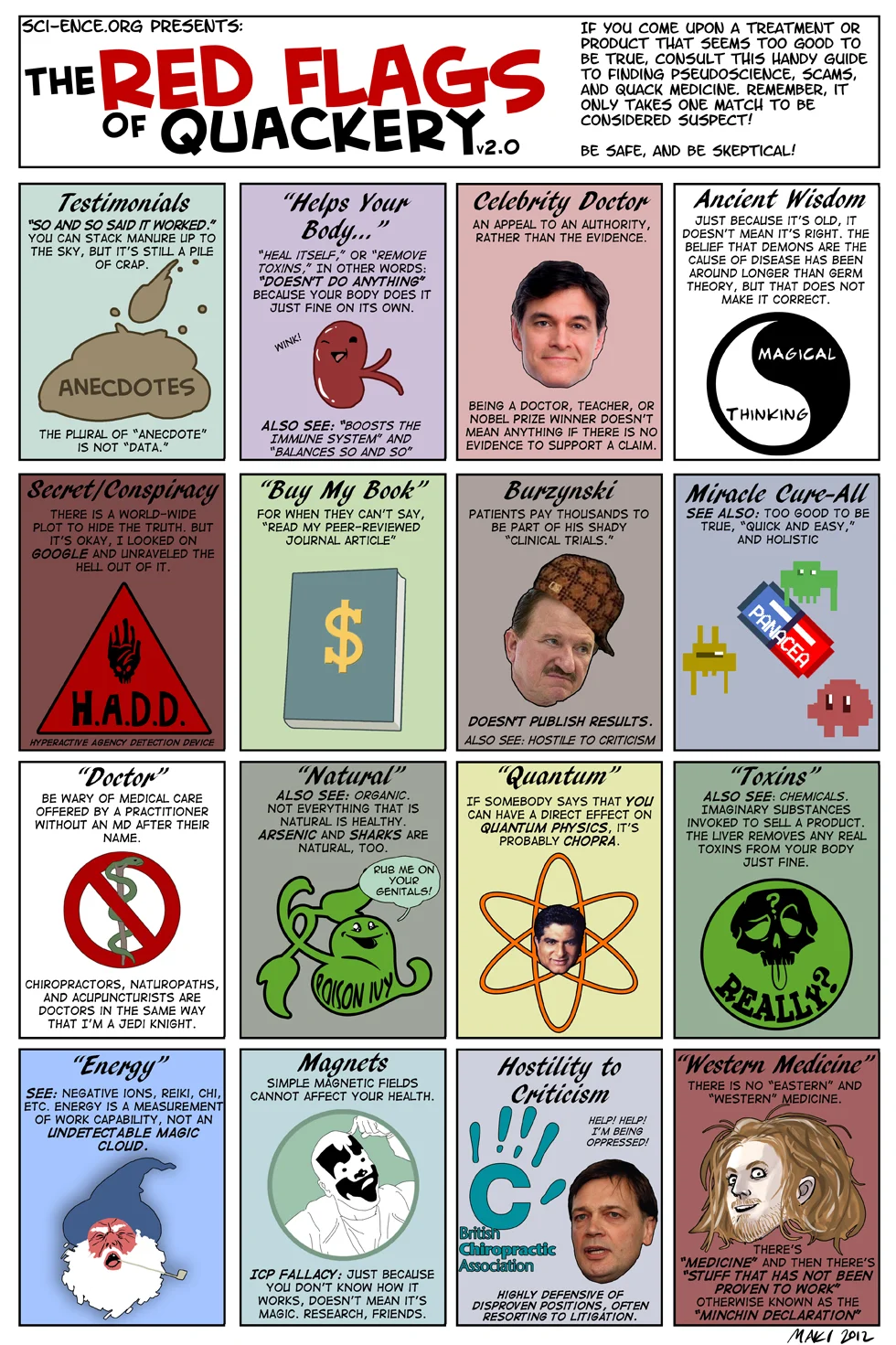

Image source. Is Steven Gundry a quack? No. He has reasonable hypotheses, then exaggerates the degree of current support for those hypotheses. He cannot be fully trusted, but his ideas should not be dismissed without much better evidence than we have now.

My son Jordan challenged me to revisit my views on Steven Gundry’s book The Plant Paradox. In order to revisit those views, I googled around to find blog posts and articles online that were critical of Gundry and followed the links. I’ll insert images of these blog posts and articles where I discuss each.

There are two parts to this reexamination of Steven Gundry’s book The Plant Paradox.. One is to revisit the key hypotheses I emphasized in my blog post review of The Plant Paradox: What Steven Gundry's Book 'The Plant Paradox' Adds to the Principles of a Low-Insulin-Index Diet. These I summarized as follows:

The War Between Plants and Animals. This is the idea that many of the natural insecticides plants produce to avoid getting eaten quite as often may have negative effects on human health.

Old and New Natural Insecticides: We and Our Gut Microbiome Have Evolved to Deal With Some Natural Insecticides, But Not Others. This is a key qualification: humans and their gut microbes should have evolved to deal with the natural insecticides from plants that our ancestors have eaten for a hundred thousand years or more, with some significant adaptation to deal with these natural insecticides for things our ancestors have eaten for ten thousand years or more.

More generally, apart from natural insecticides, the longer our ancestors have eaten a particular type of food, prepared in the way it is now prepared, the more assurance we have of its safety. Overall, the dietary there are at least four big dietary changes evolution may not have fully adapted us for:

The Agricultural Revolution, with its Emphasis on Grain

The A-1 Mutation in Cows, which Affects Milk Proteins

The Introduction of New World Plant Food

Highly Processed Food

The other views based on The Plant Paradox to reexamine are Steven Gundry’s claims about specific foods.

Note that none of this about the particular class of natural insecticides called “lectins” in general being bad, which is, I think, a distortion of Steven Gundry’s views, and certainly not something I would agree with. Lectins in foods that humans and their gut microbes have had plenty of time to adapt to should be fine. (The exception to the idea that truly ancient foods should be safe for the typical person is that one might have problems if one’s dietary patterns and other environmental factors had killed off a large share of the types of microbes that are important for dealing with the lectins in those foods.)

I view all of these claims are important hypotheses that have not been falsified by existing data. One already meets with a general consensus by scholars: (4) the idea that the highly processed food so common in modern diets is quite bad for us. I write about why in “The Problem with Processed Food.”

Another claim for which I consider the evidence to be strong—though not gold-standard evidence—is (2) the claim that A-1 milk is a problem. On that, see my posts

On claim (1), Grain is generally a problem because of its high insulin index. (See “Forget Calorie Counting; It's the Insulin Index, Stupid.”) Whether it is also a problem because of lectins is more speculative. This matters a lot for oatmeal, which is one of the grains that is lowest on the insulin index. I don’t know what to think about oatmeal. Because it is relatively low on the insulin index and has some components that are especially satiating, oatmeal has some real benefits for weight loss that may outweigh whatever lectin dangers it presents.

(Rice is fairly high on the insulin index; for rice there is a mystery about why eating a lot of rice hasn’t led to more obesity in East Asia. I certainly feel very hungry a couple of hours after I eat any substantial amount of rice. I don’t know the answer to why heavy rice-eating hasn’t led to more obesity among East Asians, especially in the context of increasing available of food to eat if the insulin kick from rice makes them hungry. I wish I knew. Two possibilities that don’t seem sufficient to explain the puzzle are (a) Jason Fung suggests that eating sour things with rice as the Japanese do at least at some meals might reduce the insulin kick from rice, (b) natural selection may have given many East Asians adaptations for rice eating—maybe, maybe such adaptations are easier than for other grains. As far as lectins go, white rice may not be very high in lectins.)

Claim (3), that new world plant food is likely to be problematic, is an especially interesting claim. Near the end of this post, I discuss tomatoes in some detail. Potatoes, like grain, are quite high on the insulin index, so I think potatoes are very unhealthy quite apart from lectins. But it is possible that lectins make them worse. Steven Gundry has gotten me worried about cashews and peanuts.

Link to the review shown above. I only know it was written by Stephen Guyenet because of the link to it in Joel Kahn’s post “Eat Your Beans but Skip Reading Dr. Steven Gundry’s ”The Longevity Paradox”: Flaws and Fruits.”

As for the other hypotheses, Stephen Guyenet agrees with me on that. In the post shown above, he repeatedly indicates his interest in these hypotheses as hypotheses, and writes:

We believe the ideas in this book should have been presented as hypotheses to be tested rather than as scientific findings.

He rates the following claims by Steven Gundry on a 0 to 4 scale as follows (I combined the text of the claim as summarized by Stephen Guyenet with the rating he gives a few paragraphs later.)

Claim 1: Lectins from grains, legumes, certain types of dairy, fruit, and nightshade and cucumber-family vegetables cause an increase in intestinal permeability (“leaky gut”). Rating: 1.7 out of 4.

Claim 2: Grains, legumes, certain types of dairy, fruit, and nightshade and cucumber-family vegetables are fattening foods because their high content of lectins stimulate energy storage and appetite. Rating: .7 out of 4.

Claim 3: Inside the body, lectins from grains, legumes, certain types of dairy, fruit, and nightshade and cucumber-family vegetables cause chronic autoimmune or other inflammatory reactions leading to a wide range of chronic diseases. 1 out of 4.

On Claim 2, I need to say that I never found Steven Gundry’s claim that nightshades and cucumber-family vegetables are fattening very convincing. (I have worried about them being harmful in ways other than their being fattening.) Grains (even whole grains), legumes and fruit can be fattening simply because they are somewhat high on the insulin index, which need not have much to do with lectins. (See “Forget Calorie Counting; It's the Insulin Index, Stupid.”) Given the number of patients that Steven Gundry has seen who have chronic autoimmune or other inflammatory reactions, and has treated with dietary restrictions, I give a fair amount of credence to the interrelated Claims 1 and 3. I agree with Stephen Guyenet that if this is indeed true, Steven Gundry needs to publish peer-reviewed articles backing up what he claims he sees in his patients with chronic autoimmune or other inflammatory reactions. If he doesn’t do so, someone else should test this. It is an important enough and credible enough claim to be worth either falsifying or confirming, whatever a careful study would show.

(Interestingly, Stephen Guyenet’s tone in discussing Steven Gundry’s highly speculative hypotheses is much more friendly than his discussion of Gary Taubes’s claim that sugar is very, very, very bad—a claim that has much better evidence to back it up. See “The Case Against Sugar: Stephan Guyenet vs. Gary Taubes” and “Layne Norton Discusses the Stephan Guyenet vs. Gary Taubes Debate (a Debate on Joe Rogan’s Podcast).” One possible reason for the difference in tone is that Steven Gundry, as a medical doctor, is much more “in the guild” than Gary Taubes, who is a journalist with physics training.)

Stephen Guyenet, like many others questioning Steven Gundry’s claims, points to abundant evidence that whole grains, legumes, fruit, nightshades and cucumber-family vegetables help reduce obesity and lead to other good outcomes. There is a very basic point to make here. Oversimplifying, suppose you could rank all foods (perhaps within category), from most health to least healthy. Given the fact that a large share of people are eating very unhealthy foods, if medium unhealthy food replaces very unhealthy food, that is a win. I don’t have a general index of the healthiness of foods, but in the particular direction of being fattening, let me take the insulin index as a reasonably good measure of how fattening a particular food is. Then this idea can be made very concrete. Eating more lentils that have an insulin index of 42 is a big improvement in relation to weight loss if those lentils are replacing potatoes, which have an insulin index of 88; but if lentils are displacing walnuts that have an insulin index of about 5, that substitution of lentils for walnuts may be a fattening change. Similarly, substituting eating whole fruit instead of candy or cake or fruit juice is a huge improvement. But acting as if eating three peach-sized pieces of fruit is as healthy as eating a similar quantity of green leafy vegetables is a mistake.

To put a point on it: whenever people cite evidence about how healthy a particular type of food is, one always needs to ask “Eaten instead of what?” Even extremely good evidence that a particular type of food is an improvement on the typical American diet does not mean that type of food isn’t problematic in ways that could be avoided by eating something even healthier.

The big problem in Michael Gregor’s attack on Steven Gundry in the video shown just above is Michael Greger’s uncritical acceptance of evidence that a certain type of food is a big improvement on what it replaces in the typical American diet as if it were evidence that food was “healthy” full stop. (That is also the big problem with Joel Kahn’s blog post “The Plant Paradox and The Oxygen Paradox: Don’t Hold Your Breath for Health” and Toby Amidor’s blog post “Ask the Expert: Clearing Up Lectin Misconceptions.”)

The other problem with this video is that Steven Gundry is not, in the end, anti-bean and anti-lentil. He simply says that they need to be cooked carefully—he recommends presoaking and pressure-cooking—in order to destroy as many of the lectins as possible. Presoaking is not at all an unusual type of preparation for beans and lentils. Some people claim that regular cooking is adequate without pressure-cooking. That is indeed a dispute, but not a huge dispute.

Steven Gundry takes his view that animal protein is problematic from T. Colin Campbell and Thomas Campbell, as I do. (See “Meat Is Amazingly Nutritious—But Is It Amazingly Nutritious for Cancer Cells, Too?” and “How Sugar, Too Much Protein, Inflammation and Injury Could Drive Epigenetic Cellular Evolution Toward Cancer.”) But the Campbells do not seem to realize that Steven Gundry is an ally. As strong proponents of a vegan diet, the Campbells seem to be concerned that by recommending some plant foods over others, Steven is unduly limiting the range of options for a vegan diet. They also are concerned that Steven Gundry allows animal foods in moderation in his recommendations.

The most useful aspect of the Campbell’s article shown above is that it details how inappropriate Steven Gundry is with his citations. The citations often are to low-quality sources or to sources that don’t back up what Steven Gundry is saying at all. The Campbells are especially convincing that Steven Gundry is not completely trustworthy in what he says. This of course does not make Steven Gundry’s hypotheses bad hypotheses. It does mean that Steven Gundry can’t be trusted to give us the information to carefully evaluate the limited evidence so far on whether those hypotheses are true or not.

The most interesting thing about “larkasaur’s” review of The Plant Paradox shown just above is his nice discussion of the evidence for anticancer properties of lectins. Larkasaur writes:

Some lectins have anti-cancer properties - but at the same time, this means they are powerful substances that might also cause harm, as Dr. Gundry proposes.

Indeed, a hole in Steven Gundry’s argument that natural insecticides might be hard on cells is that they might be even harder on cancer cells in a way that made them a very mild, and relatively safe type of preventive “chemotherapy.” Of course, I think that fasting is a much better way to go for a likely effective, mild and safe form of preventive “chemotherapy.” My diet and health posts focusing on cancer give a fairly good treatment of this idea:

How Fasting Can Starve Cancer Cells, While Leaving Normal Cells Unharmed

Meat Is Amazingly Nutritious—But Is It Amazingly Nutritious for Cancer Cells, Too?

The bottom-line is that if lectins are more harmful to otherwise healthy cells than fasting is, and no harder on cancer than fasting, then fasting rather than lectins is the better way to try to prevent cancer. Of course, if certain lectins work as chemotherapy after someone has already been diagnosed with cancer, that would be great. (See for example this abstract: “Lectins as bioactive plant proteins: a potential in cancer treatment.”) And any anti-cancer effects of lectins have to be weighed in the balance when judging particular foods. Here one would want to know “How hard on cancer?” and “How hard on healthy cells?” for each different type of lectin.

One place where larkasaur powerfully countered one of Steven Gundry’s claims about a specific lectin is this passage, which begins with a quotation from The Plant Paradox, followed by larkasaur’s counter:

The lectin WGA (wheat germ agglutinin) ... can attach to the insulin docking port as if it were the actual insulin molecule, but unlike the real hormone, it never lets go - with devastating results, including reduced muscle mass, starved brain and nerve cells, and plenty of fat.

His reference for this is Effects of wheat germ agglutinin on insulin binding and insulin sensitivity of fat cells. I didn't see the full paper, but from the abstract, this was an in vitro study where WGA actually increased insulin sensitivity at low concentrations, but decreased it at high concentrations. I couldn't find evidence from other studies that the actual blood concentrations of WGA that someone might get from their diet, could affect insulin sensitivity. I did find some evidence that increased intake of whole grains vs refined grains (and whole grains have more WGA) improves insulin sensitivity - e.g. Effect of whole grains on insulin sensitivity in overweight hyperinsulinemic adults. I even found something about wheat germ supplementation alleviating insulin resistance. Wheat germ has a lot more WGA than other wheat products.

Larkasaur also questions some specific claims about Neu5AC and Neu5GC. I was convinced that I should disregard Steven Gundry’s claims about Neu5AC and Neu5GC (which I didn’t pay very much attention to when I read The Plant Paradox in any case).

I really like larkasaur’s discussion of Steven Gundry’s study. Larkasaur writes:

He did a trial on 1000 people, which was presented at an American Heart Assoc. conference. 800 of them had either an autoimmune disease themselves or a family member with an autoimmune disease. They were asked to eat his diet, which "consisted of avoidance of grains, sprouted grains, pseudo-grains, beans and legumes, soy, peanuts, cashews, nightshades, melons and squashes, and non-Southern European cow milk products (Casein A1), and grain and/or bean fed animals.", and adiponectin and TNF-alpha levels were measured every 3 months.

Their levels of TNF-alpha normalized within 6 months, but the adiponectin levels remained elevated.

So he concluded that "TNF-alpha can be used as a marker for gluten/lectin exposure in sensitive individuals."

But he doesn't say how those 1000 people were selected. Maybe they were cherry-picked to show a good result.

And, he didn't have a control group. A control group might consist of people eating his Plant Paradox diet, but also taking a capsule with wheat germ agglutinin (wheat lectin), so that they would be getting the same amount of lectins that people eating the average American diet do. And there would also be a test group, of people eating his Plant Paradox diet and taking a capsule with placebo. That would test whether WGA actually has the effects that he thinks it does.

In addition to dismissing the dangers of A-1 milk to quickly, Larkasaur is too trusting of the official recommendations about the daily requirement for Vitamin D. On that, see

Michael Matthews has a strongly worded title to his long post: “Dr. Gundry’s Plant Paradox Debunked: 7 Science-Based Reasons It’s a Scam.” Here are his Michael’s “7 Science-Based Reasons It’s a Scame”:

The healthiest people in the world eat a lot of lectins.

There’s no real scientific debate about the nutritional value of fruits and vegetables.

Lectins don’t make you fat, overeating does.

Lectins don’t give you heart disease.

Lectins don’t cause “leaky gut” unless you have celiac disease.

Humans have been eating lectins a very, very long time.

Cooking lectins nullifies any potential negative side effects.

1 and 2 are subject to my point above that a food can be demonstrably better than the typical American diet or other typical modern diet, but still have problematic elements. 1 and 6 are subject to the point that Steven Gundry is not claiming that all lectins are harmful, but only that lectins we have not had adequate evolutionary time to adapt to are harmful (though Steven Gundry may be somewhat inconsistent in realizing that this is the position he has to be taking given his logic). On 3, the Michael saying that “overeating makes you fat” leaves unanswered the key question: “What makes you overeat?” Steven Gundry is trying to answer the question of “What makes you overeat?” Anyone who thinks the answer to the question “What makes you overeat?” is either uninteresting or obvious is misguided given where we are in the science. As for 4 and 5, at least in his section headings, Michael is treating “unproven” as the same as “proven false.” No! These are important hypotheses that we don’t have adequate evidence on either way. Finally, on 7, Michael might be right. This is the debate I mentioned earlier about whether pressure-cooking is necessary to destroy most lectins, as Steven Gundry says, or whether regular cooking is enough. As a minor cavil, I do think that Michael Matthews uses the word “nullify” inappropriately about the effect of soaking in reducing lectins by 50%. But the following passage as a whole is useful:

According to a study conducted by scientists at the University of Sao Paulo, boiling beans and other lectin-containing foods for 15 minutes is enough to eliminate almost all of the lectin content. If you use a pressure cooker you can achieve the same effect in just 7.5 minutes, but the end result is the same.

As the scientists put it, “In relation to lectins, there seems to be no residual activity left in properly processed legumes.”

Soaking is another effective method for nullifying lectins. In a study conducted by scientists at Michigan State University, soaking red kidney beans for 12 hours reduced the lectin content by 50%.

Fruit, Nightshades and Other Vegetables with Seeds

Overall, while I think fruit should be eaten in moderation, I think Steven Gundry’s views are too negative about fruit. Many types of fruit are relative high on the insulin index. But I doubt the lectins in fruits are a particular problem. Hence, in relation to fruit, let me recommend that you stick with what I said about fruit in “Forget Calorie Counting; It's the Insulin Index, Stupid” and ignore what Steven Gundry says about fruit. I am a little torn about whether or not it is OK to eat the skin, which Steven Gundry advises against.

Other than the nightshades, such as tomatoes, peppers, potatoes, and eggplant, the same principles should apply to the botanical fruits that we usually call vegetables, such as cucumbers—except that eating the seeds (or the skin) might be a problem.

On the nightshades, Steven Gundry recommends that they be deskinned, deseeded and pressure cooked. This may be reasonably close to the way many tomato products are made. Because I love fresh tomatoes, I have tried to research whether there is strong positive evidence that they are healthy that could overturn Steven Gundry’s claims that they are problematic. But what I have found is that the bulk of the evidence in nutritional trials about tomatoes is about tomato products that have been processed in the sorts of ways Steven Gundry recommends.

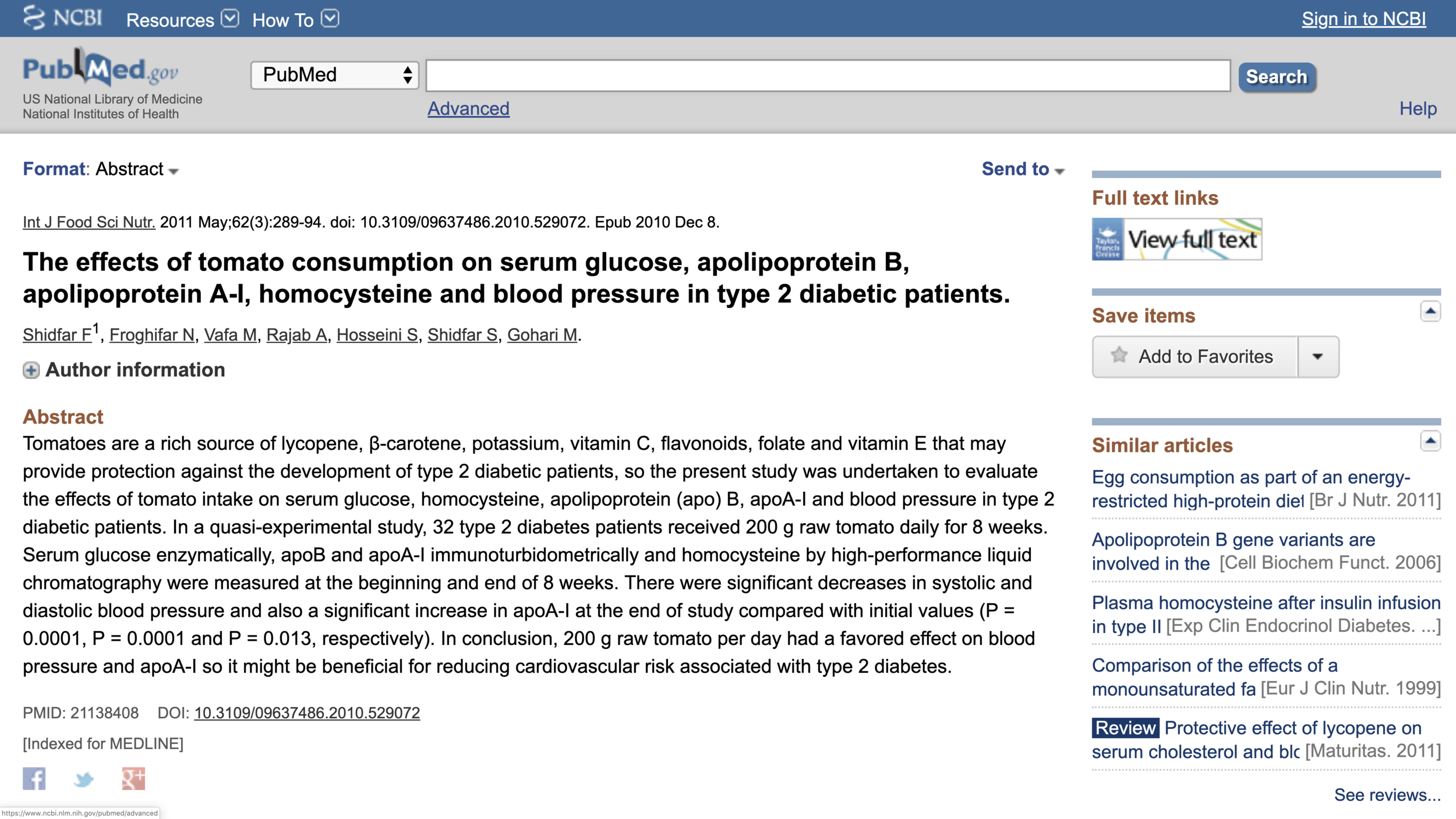

Looking for evidence about the dietary effects of fresh tomatoes, I did find a set of references in the article shown above: “Whole Food versus Supplement: Comparing the Clinical Evidence of Tomato Intake and Lycopene Supplementation on Cardiovascular Risk Factors.”

Here are abstracts for four articles involving fresh tomatoes:

My summary of these abstracts is that while tomato products might reduce inflammation, whole tomatoes are neutral for inflammation, which one might imagine was due to an inflammation-reducing effect of the rest of the tomato (at least when cooked) combined with inflammation-increasing effects of the skin and seeds. But there is some evidence that whole tomatoes seem to reduce blood pressure, raise good cholesterol and reduce oxidative damage. So, overall, fresh tomatoes sound good overall, though skinned, deseeded, cooked tomatoes might be better. The big question I have about these studies are whether those benefits are only when tomatoes are added to a typical American diet (likely displacing some very bad foods), or whether those benefits would be there for me given the diet I am starting from (which currently doesn’t include any fresh tomatoes).

Sometime I should try to do similar kind of online searching for research about eggplant and peppers. (As I mentioned above, I don’t feel I need to do more research about potatoes because they are so high on the insulin index, I am confident they are best avoided.)

Some Favorable Evidence for Steven Gundry’s Claims

On the basic idea that lectins are powerful in their effects on humans, take a look at this abstract:

Finally, here is a post that is relatively supportive of Steven Gundry’s claims:

Here are some of John O’Connors grades for Steven Gundry claims, along with quotations from some of the associated text:

Altered gut microbiome drives lectin sensitivity: C+

Add to the list of medications we take the presence of toxic chemicals in everything from cookware to mattresses, and the rise of GMO crops sprayed with known carcinogens like glyphosate, it’s not unreasonable to assume some people might not be equipped with the microbes to properly digest certain lectins. Lectins are controversial, but increased pollution, prescription medications and widespread use of antibiotics seems to be changing the shape of our microbiomes. In his paper, Do Dietary Lectins Cause Disease, allergist David L.J. Freed theorizes that a serious infection could be the triggering event that alters the microbiome in such a way that we become prone to lectin sensitivity and certain autoimmune conditions.

The altered microbiome theory is gaining traction as consensus fact, and it’s imbalances of the gut that drive Gundry’s claims about lectin. Some have cast him as an outsider, but he’s right in the mainstream of functional medicine. He argues that many people are so used to low levels of inflammation caused by lectin that a state of reduced performance is their “new normal.” But even assuming that a large percentage of the population thrives on lectin, that doesn’t mean we all do.

For example, could a C-section birth, which is thought to be deprive babies of important foundational microbes, combined with a serious infection and a few rounds of broad spectrum antibiotics be just what the doctor ordered for a problem with digesting lectins down the road?

Lectins travel to distant organs: B-

There is even some evidence that lectins can travel to the brain. This study is footnote #5 in the Plant Paradox, and it demonstrates (albeit in a worm model) that lectins can travel from the gut to the brain by way of the Vagus nerve where they impact the function of neurons, offering an alternative theory on the cause and development of Parkinson’s disease.

Again, the study cited by Gundry is a worm model, and it’s on the frontier of nutrition science, but nonetheless, there are other papers that show benefits to mental health when removing grains, so it’s something to experiment with and keep in mind when testing out theories behind anxiety for example. This Danish study showed a 40% reduction in Parkinson’s disease in people who had their Vagus nerve removed.

Lectins and heart disease: C

Peanut oil is high in lectin. In a study titled “Lectin may contribute to the atherogenicity of peanut oil,” researchers found that when lectin was reduced in peanut oil by washing, incidence of heart disease dropped significantly in animal models (mice, rabbits and primates).

Lectins can break down the gut wall: A

Wheat proteins do us harm by attacking the gut lining, making the barrier between our intestines and the inside of the body more permeable, which for some, can lead to symptoms ranging from digestive issues to achy joints to problems with mental health. (R) Zonulin, a protein which can break apart the “intracellular tight junctions” of the gut wall, is produced when we eat wheat. The theory of leaky gut is that the resulting intestinal permeability lets all sorts of bad guys into our blood stream and the immune system goes wild as a result. (R) One of the most successful dietary interventions used to treat Rheumatoid Arthritis is a gluten free Vegan/Vegetarian diet. Of note: some of these RA diet studies have found an “association between disease activity and intestinal flora indicating impact of diet on disease progression.”

Conclusion

Steven Gundry’s hypotheses should be taken very seriously. Both Steven Gundry himself and other researchers should take them as important claims to be proven or disproven by solid evidence. In the meantime, eating low on the insulin index is likely to get you most of the benefits of the Gundry diet. But if you have any chronic autoimmune or other inflammatory reactions, my recommendation is that it would be worth your while to try to follow the full Gundry yes and no list of foods, see if it helps, and if it does, only reintroduce foods you have subtracted one at a time so you can see if some particular food is a problem for you.

For annotated links to other posts on diet and health, see:

For example, here is what the first section looks like:

I. The Basics

Governments Long Established Should Not—and to a Good Approximation Will Not—Be Changed for Light and Transient Causes

A key passage of the Declaration of Independence is:

Prudence, indeed, will dictate that Governments long established should not be changed for light and transient causes; and accordingly all experience hath shewn, that mankind are more disposed to suffer, while evils are sufferable, than to right themselves by abolishing the forms to which they are accustomed. But when a long train of abuses and usurpations, pursuing invariably the same Object evinces a design to reduce them under absolute Despotism, it is their right, it is their duty, to throw off such Government, and to provide new Guards for their future security.

In this passage, those who had a hand in crafting the Declaration of Independence show their knowledge of John Locke’s 2d Treatise on Government: Of Civil Government. In Chapter XIX, sections 223-225, John Locke writes:

§. 223. To this perhaps it will be said, that the people being ignorant, and always discontented, to lay the foundation of government in the unsteady opinion and uncertain humour of the people, is to expose it to certain ruin; and no government will be able long to subsist, if the people may set up a new legislative, whenever they take offence at the old one. To this I answer, Quite the contrary. People are not so easily got out of their old forms, as some are apt to suggest. They are hardly to be prevailed with to amend the acknowledged faults in the frame they have been accustomed to. And if there be any original defects, or adventitious ones introduced by time, or corruption; it is not an easy thing to be changed, even when all the world sees there is an opportunity for it. This slowness and aversion in the people to quit their old constitutions, has, in the many revolutions which have been seen in this kingdom, in this and former ages, still kept us to, or, after some interval of fruitless attempts, still brought us back again to our old legislative of king, lords and commons: and whatever provocations have made the crown be taken from some of our princes heads, they never carried the people so far as to place it in another line.

§. 224. But it will be said, this hypothesis lays a ferment for frequent rebellion. To which I answer, 19 First, No more than any other hypothesis: for when the people are made miserable, and find themselves exposed to the ill usage of arbitrary power, cry up their governors, as much as you will, for sons of Jupiter; let them be sacred and divine, descended, or authorized from heaven: give them out for whom or what you please, the same will happen. The people generally ill treated, and contrary to right, will be ready upon any occasion to ease themselves of a burden that sits heavy upon them. They will wish, and seek for the opportunity, which in the change, weakness and accidents of human affairs, seldom delays long to offer itself. He must have lived but a little while in the world, who has not seen examples of this in his time: and he must have read very little, who cannot produce examples of it in all sorts of governments in the world.

§. 225. Secondly, I answer, such revolutions happen not upon every little mismanagement in public affairs. Great mistakes in the ruling part, many wrong and inconvenient laws, and all the slips of human frailty, will be borne by the people without mutiny or murmur. But if a long train of abuses, prevarications and artifices, all tending the same way, make the design visible to the people, and they cannot but feel what they lie under, and see whither they are going; it is not to be wondered at, that they should then rouze themselves, and endeavour to put the rule into such hands which may secure to them the ends for which government was at first erected; and without which, ancient names, and specious forms, are so far from being better, that they are much worse, than the state of nature, or pure anarchy; the inconveniences being all as great and as near, but the remedy farther off and more difficult.

On a much larger scale, this claim is like the claim that for every person who complains about a product, there are many, many other people who felt the same way, but felt it was too much trouble or too scary to lodge a complaint. Dissatisfaction with a government passes through a strong filter before any revolution comes out.

We live in a time when new political forces are arising both on the right and on the left. One might ask “Is this just polarization, or has our government genuinely heaped a long train of abuses on the American people that partisans interpret in different ways?” I tend to thing the answer is still that it is just polarization. What the right complains about is quite different from what the left complains about. And in US presidential elections, the electorate seems close to evenly divided in complaining about very different things. So I don’t think it is time to change the US government in any big way. Regular elections should give the American people a chance to change what is wrong with government decisions if they can agree on which government decisions are wrong.

For links to other John Locke posts, see these John Locke aggregator posts:

Confessions of a Supply-Side Liberal an Intelligent Economist Top 100 Economics Blog

Here is a quotation from Prateek Agarwal’s email to me about this honor:

… your blog, Confessions of a Supply Side Liberal has been featured in the Top 100 Economics Blogs of 2019. Congratulations!

One of the significant changes this year has been the removal of newspaper blogs such as Bloomberg View and Real Time Exchange to focus on more niche blogs. The lack of female economist (and bloggers) has been a common criticism of this list. I've made an effort to include more female bloggers, but if you have any suggestions, I can consider them for the 2020 list.

I’d be glad for suggestions from readers of good blogs by female economists that didn’t make it onto this list that I can pass on to Prateek.

Hints About What Can Be Done to Reduce Alzheimer's Risk

I have a simple rule of thumb: if we have known of a disease for a long time, but understand it even less well then we understand cancer, it is probably an autoimmune disease or the side effect of an immune system reaction to diet, infection, toxins or physical trauma. I am thinking in particular of two black beasts (bêtes noires) of old age: Alzheimer’s disease and Parkinson’s disease. In both of these two cases, suspecting that they may be autoimmune diseases is well within the scope of the current scholarly debate (Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s). And the immune system process of inflammation is seen as a risk factor for Alzheimers. (On inflammation more generally, see my post “Jonathan Shaw: Could Inflammation Be the Cause of Myriad Chronic Diseases?”

For those who either have or think they might have an autoimmune disease or are worried about diseases such as Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s that might be autoimmune diseases or diseases with an important part of the causal mechanism involving the immune system, it is worth knowing about Steven Gundry’s hypothesis that leaky gut and certain foods often generate or aggravate autoimmune disorders. See “What Steven Gundry's Book 'The Plant Paradox' Adds to the Principles of a Low-Insulin-Index Diet.”

In this post, let me focus in on Alzheimer’s disease and leave Parkinson’s disease for another day. Researchers haven’t been able to provide gold standard evidence for anything as a preventative against Alzheimer’s disease. In her Wall Street Journal article “Should You Find Out if You’re at Risk of Alzheimer’s?”, Sumathi Reddy reports:

There is no advice derived from randomized-controlled trials—the gold standard in medicine—on preventing Alzheimer’s disease.

The title of Sumathi’s article alludes to these three facts:

Genetic tests are getting a lot better at predicting Alzheimer’s disease

They’ll get better still by adding in the effects of more genes and pinning down the effect of each gene more and more precisely.

In the absence of good evidence about how to try to prevent Alzheimer’s disease, you may or may not want to know about your genetic level of Alzheimer’s risk.

But even in the absence of solid evidence, many researchers and doctors have the intuition that what is good for avoiding heart disease may also be good for fighting Alzheimer’s disease. (Cynically, I wonder a little if they say that because even if they are wrong about the effects on Alzheimer’s they won’t get in trouble for recommending those things.) Let’s look at some specific statements by researchers and doctors. In each case, let me add bold italics to emphasize the key message in each of the quotations from Sumathi’s article.

Rudy Tanzi’s Advice for Trying to Prevent Alzheimer’s Disease

But most doctors agree that regular exercise, adequate sleep and a heart-healthy diet can lower the risk. “The Healing Self,” which Dr. Tanzi wrote with Deepak Chopra, advocates for protecting the brain by focusing on sleep, exercising, learning things, controlling stress and hypertension, as well as maintaining social interaction and a healthy diet.

David Holtzman’s Advice for Trying to Prevent Alzheimer’s

David Holtzman, professor and chair of neurology at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis, says there is no objective data that specific strategies work aside from a 2015 study conducted in Finland that showed that elderly people who were cognitively normal or had a mild impairment maintained or increased their cognitive ability over two years with exercise, cognitive training and vascular-risk monitoring.

“Right now,” Dr. Holtzman said, “if you lead an active, heart-healthy, pro-brain lifestyle, there’s not much that we can tell somebody that they should do differently.”

Dale Bredesen’t Advice for Trying to Prevent and Fight Alzheimer’s Disease

Dale Bredesen, a professor in the department of molecular and medical pharmacology at UCLA and founding president of the Buck Institute for Research on Aging, advocates for specific changes. His protocol—which costs $75 a month—entails getting regular blood tests to track markers such as insulin resistance and inflammation, as well as following a low-carb, high-fat diet, fasting intermittently and taking supplements. Dr. Bredesen says he has published two small studies and one 100-person study showing that his protocol can reverse cognitive decline in patients with mild cognitive impairment or Alzheimer’s disease.

Dale has gotten some pushback on this. He answers that he is working toward getting more solid evidence:

But experts pointed out that his studies aren’t randomized controlled ones. Dr. Bredesen said he needs to build up anecdotal evidence to be able to do one. Many members of the ApoeE4.Info group, including Ms. Braymer, said they follow the principles of Dr. Bredesen’s protocol.

It is interesting to look at the Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease & Parkinsonism article “Reversal of Cognitive Decline: 100 Patients” that Dale Bredesen is the first author for.

Here are some informative quotations from that article, again with my emphasis added both by bold italics on the words of the article and by adding explanations in square brackets:

… what is referred to as Alzheimer’s disease is a protective, network-downsizing response to several classes of insults: pathogens/inflammation, toxins, and withdrawal of nutrients, hormones, or trophic [diet-related] factors.

This notion has led to a treatment regimen in which … a personalized program is generated … Some examples include: (1) identifying and treating pathogens such as Borrelia, Babesia, or Herpes family viruses; (2) identifying gastrointestinal hyperpermeability, repairing the gut, and enhancing the microbiome [leaky gut and a messed-up gut microbiome—the causal nexus Steven Gundry emphasizes]; (3) identifying insulin resistance and protein glycation [sugar molecules messing up proteins], and returning insulin sensitivity and reduced protein glycation; (4) identifying and correcting suboptimal nutrient, hormone, or trophic [diet-related] support (including vascular support); (5) identifying toxins (metallotoxins and other inorganics, organic toxins, or biotoxins), reducing toxin exposure, and detoxifying.

Here we have taken a very different approach, evaluating and addressing the many potential contributors to cognitive decline for each patient. This has led to unprecedented improvements in cognition. Most importantly, the improvement is typically sustained unless the protocol is discontinued, and even the initial patients treated in 2012 have demonstrated sustained improvement. This effect implies that the root cause(s) of the degenerative process are being targeted, and thus the process itself is impacted, rather than circumventing the process with a monotherapeutic that does not affect the pathophysiology.

Let’s hope that some of this advice for trying to prevent Alzheimer’s is right, or that better advice is coming soon.

For annotated links to other posts on diet and health, see “Miles Kimball on Diet and Health: A Reader's Guide.”

In relation to Cancer, which I mentioned at the beginning of this post, you might be interested in these:

How Fasting Can Starve Cancer Cells, While Leaving Normal Cells Unharmed

Can Religion Reduce Suicide?

I was quite interested to read the scientific article “Association Between Religious Service Attendance and Lower Suicide Rates Among US Women,” by Tyler J. VanderWeele, Shanshan Li, Alexander C. Tsai and Ichiro Kawachi. I was wondering by what magic they were hoping to get the causal effect of religious attendance on suicide from the non-experimental data in the Nurse’s Health Study. (I wrote about dietary evidence in the Nurse’s Health Study and the statistical issues in interpreting that evidence in “Hints for Healthy Eating from the Nurse's Health Study.”)

It would have been interesting to see the regression coefficient for a change in religious attendance. Unfortunately, it seems they didn’t look at that, but rather “controlled” for past religious attendance. “Controlling” for a variable by including it in a regression isn’t really controlling for what that variable is intended to measure or is proxying for when that variable is measured with error relative to what it is proxying for. It is only partially controlling. Whether or not one is “controlling” for variables can only be verified when one explicitly thinks through measurement error issues. And “controlling” for variables is seldom achieved without thinking through measurement error issues. (The advantage of using the first difference of religious attendance as a right-hand-side variable is that the first difference of religious attendance should measure the true change in whatever religious attendance is intended as a proxy, plus error. The error should bias the coefficient toward zero, but is less likely to change the sign and statistical significance of the sign of the coefficient.)

But the biggest issue with the paper lies in a different direction. They recognize the issue and try to parry it in these passages:

For an unmeasured confounder to explain the HR estimate of 0.16 (95% CI, 0.06-0.46), the unmeasured confounder would have to both increase the likelihood of religious service attendance and decrease the likelihood of suicide by 12-fold above and beyond the measured confounders; weaker confounding would not suffice. To bring the estimate’s upper confidence limit of 0.46 above 1.0, the unmeasured confounder would still have to both increase the likelihood of religious service attendance and decrease the likelihood of suicide by 3.7-fold above and beyond the measured confounders.

…

Our study made use of observational data. Although we adjusted for major confounders regarding the association between religious service attendance and suicide, the results may still be subject to unmeasured confounding by personality, impulsivity, feelings of hopelessness, or other cognitive factors. However, in sensitivity analysis, for an unmeasured confounder to explain the effect of religious service attendance on suicide, it would have to both increase the likelihood of religious service attendance and decrease the likelihood of suicide by greater than 10-fold above and beyond the measured covariates. Such substantial confounding by unmeasured factors seems unlikely, given adjustment for an extensive set of covariates and the known risk factor associations for suicide.

Unlike the authors, it is not hard for me to think of a very powerful potential confounder. Having one’s life be a mess could easily both reduce religious attendance powerfully and powerfully increase the probability of suicide. That is a story in which there wouldn’t have to be any causal effect of religious attendance on suicide at all.

Note that one’s life being a mess could both lead to more suicide and reduce any kind of social engagement and community support. So this is a problem not just for showing that religiosity can reduce suicide—which it might through social support and community—but for showing that any other kind of social support and community reduces suicide.

Even if something religious is causally reducing suicide, it definitely doesn’t have to be religious attendance. Anything correlated with religious attendance could also yield the evidence they point to. To see this point, suppose someone very much wanted to attend church, but was geographically too far away to make it feasible. One could easily imagine that if there are religious forces that reduce suicide, many of them might still be operative. Indeed, the authors recognize that it might be a matter of religious belief that both helps lead to religious attendance and reduces suicide:

Although religious service attendance has commonly been used in previous published studies and tends to be the strongest religious predictor of health, religiosity is multidimensional, and different aspects of religion and spirituality may therefore be differently associated with suicide. Data on religious service attendance were collected through a self-reported questionnaire and, moreover, may be subject to measurement error and possible overreporting, although the relative ordering of frequency might still be preserved. Further research could examine other religious practices, mindfulness practices, other aspects of spirituality and religiosity, other race/ethnic and demographic groups, and other forms of social participation.

In the whole paper, the most persuasive evidence about the effect of religiosity on suicide is that religious attendance seemed to have a bigger proportional effect on Catholics than on Protestants. The best I can come up with as confounders for this results are

Relative to Protestant teaching, Catholic teaching doesn’t stop people from committing suicide, but makes people underreport suicide more if they are a believing and attending Catholic. And those who provide or withhold crucial evidence on cause of death often have similar religious beliefs and attendance to the one who died. This could in principle be addressed by looking at differences between the attendance of the one who died versus the attendance of the ones who provided or withheld crucial evidence about the cause of death.

Relative to Protestant teaching, Catholic teaching makes people especially unwilling to attend when their lives are in a mess.

Despite these possible stories (which may or may not be true and may or may not have any oomph to them), the fact that the differential content of Catholicism vs. Protestantism seems to matter is the strongest evidence they have that there is causality running from religiosity to reduced suicide.