David Ludwig: It Takes Time to Adapt to a Lowcarb, Highfat Diet

In my diet and health posts, I have emphasized fasting as a key tool for weight loss. I have also emphasized how much harder fasting is if one is eating a lot of carbs or other foods that have a high insulin index. (See “Forget Calorie Counting; It's the Insulin Index, Stupid” and “Why a Low-Insulin-Index Diet Isn't Exactly a 'Lowcarb' Diet.”) This is an issue over several time scales:

Insulin secretion stimulated by high-insulin-index foods contributes to appetite in the next few hours.

Eating carbs may make it tougher to convert over to body-fat burning over the course of the next day.

In addition, David Ludwig, in his post “Adapting to Fat on a Low-Carb Diet,” discusses evidence that for people who have, in general, been eating a highcarb diet, it takes at least three weeks to adjust to powering the brain from fat instead of powering the brain from carbs.

What this means is that you should go off sugar and be eating low on the insulin index in other dimensions for at least three weeks (and I would recommend at least six weeks) before trying to add fasting to your health and weight-loss regimen. That is, worry about “Letting Go of Sugar” and otherwise eating low on the insulin index for six weeks before trying to incorporate the insights of “Stop Counting Calories; It's the Clock that Counts,” “Jason Fung's Single Best Weight Loss Tip: Don't Eat All the Time” and “Lisa Drayer: Is Fasting the Fountain of Youth?” into your life. (“Obesity Is Always and Everywhere an Insulin Phenomenon” and “4 Propositions on Weight Loss talk about both steps.)

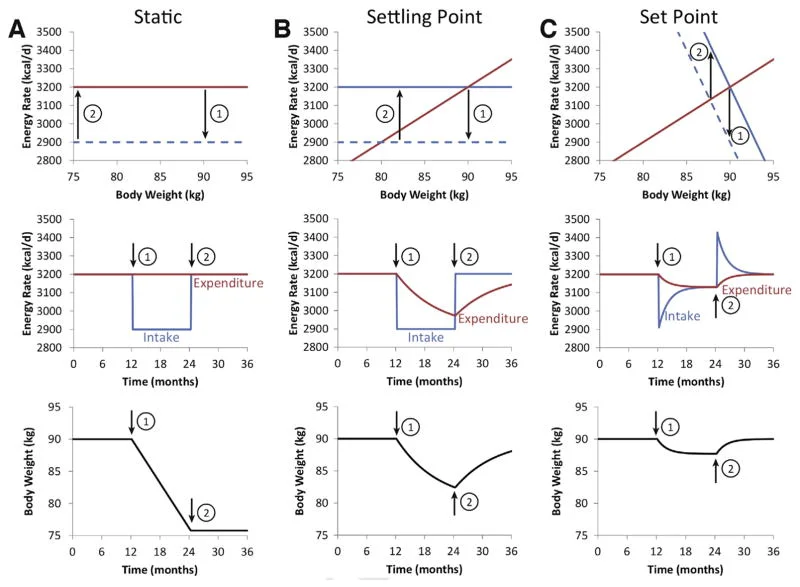

Another consequence if this at-least-three-week adaptation period for power the brain more from fat and less from carbs is that studies of lowcarb diets that last only a few weeks make lowcarb diets look worse than they really are. During the adjustment process, if your brain feels undernourished because it is used to carbs you are cutting back on, that could easily make you feel less energetic and raise your appetite. Think about metabolic ward studies in which what people eat is totally controlled. In metabolic ward studies of lowcarb, highfat diets versus lowfat, highcarb diets, the first three weeks of data will just be the adjustment period and should be disregarded if the sample is of people who are not initially adapted to a lowcarb, highfat diet. The two options for researchers is to run longer metabolic ward studies or to have a design with an initial sample drawn from two groups: one group drawn from people who have been doing a lowcarb, highfat diet for a long time in their regular life and the other group drawn from people who have been doing a lowfat highcarb diet. Then each group can be randomized in the metabolic ward into a lowcarb, highfat diet or a lowfat, highcarb diet. That randomizes each individual into either a diet similar in macronutrients to what they are used or to a diet that is quite different from what they are used to.

This matters for Kevin Hall’s and Juen Guo’s meta-analysis in “Obesity Energetics: Body Weight Regulation and the Effects of Diet Composition” of resting energy expenditure and other dimensions of energy expenditure with lowcarb, highfat versus lowfat highcarb diets. It is much easier to do short metabolic ward studies than long ones, and most metabolic ward studies have not tried to get samples of people who had distinctive dietary patterns in their regular lives before the studies. Therefore, their meta-analytic results are not the strong evidence it purports to be on the effect of these diets in the long run: if the bulk of the studies in a meta-analysis all have the same bias, that bias affects the meta-analytic summary results as well. It is not good enough to say something like “Metabolic ward studies lasting more than a few weeks are very hard to do.” Either you figure out a strategy that identifies differences between the effects of lowcarb, highfat diets and lowfat, highcarbs in the long run, or you say that the evidence can’t speak to the issue.

(When evidence is inadequate, people still need to decide what to do and often also make a decision on what to advise others to do. That is inevitable, but anyone doing so should freely admit the weakness of evidence when queried about it. And where theory comes in, they should freely explain the theoretical framework they are coming from in judging the evidence.)

An even more important research area is to look at the complementarity between lowcarb, highfat diets and fasting, both for effectiveness and for people’s ability to stick with the program.

Don’t miss my other posts on diet and health:

I. The Basics

Jason Fung's Single Best Weight Loss Tip: Don't Eat All the Time

What Steven Gundry's Book 'The Plant Paradox' Adds to the Principles of a Low-Insulin-Index Diet

David Ludwig: It Takes Time to Adapt to a Lowcarb, Highfat Diet

II. Sugar as a Slow Poison

Best Health Guide: 10 Surprising Changes When You Quit Sugar

Heidi Turner, Michael Schwartz and Kristen Domonell on How Bad Sugar Is

Michael Lowe and Heidi Mitchell: Is Getting ‘Hangry’ Actually a Thing?

III. Anti-Cancer Eating

How Fasting Can Starve Cancer Cells, While Leaving Normal Cells Unharmed

Meat Is Amazingly Nutritious—But Is It Amazingly Nutritious for Cancer Cells, Too?

IV. Eating Tips

Using the Glycemic Index as a Supplement to the Insulin Index

Putting the Perspective from Jason Fung's "The Obesity Code" into Practice

Which Nonsugar Sweeteners are OK? An Insulin-Index Perspective

V. Calories In/Calories Out

VI. Other Health Issues

VII. Wonkish

Framingham State Food Study: Lowcarb Diets Make Us Burn More Calories

Anthony Komaroff: The Microbiome and Risk for Obesity and Diabetes

Don't Tar Fasting by those of Normal or High Weight with the Brush of Anorexia

Carola Binder: The Obesity Code and Economists as General Practitioners

After Gastric Bypass Surgery, Insulin Goes Down Before Weight Loss has Time to Happen

A Low-Glycemic-Index Vegan Diet as a Moderately-Low-Insulin-Index Diet

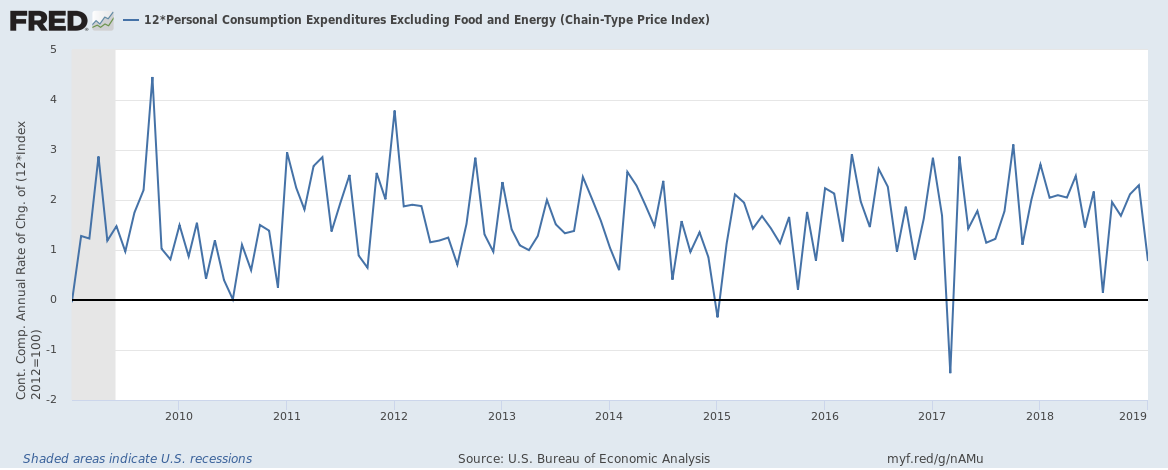

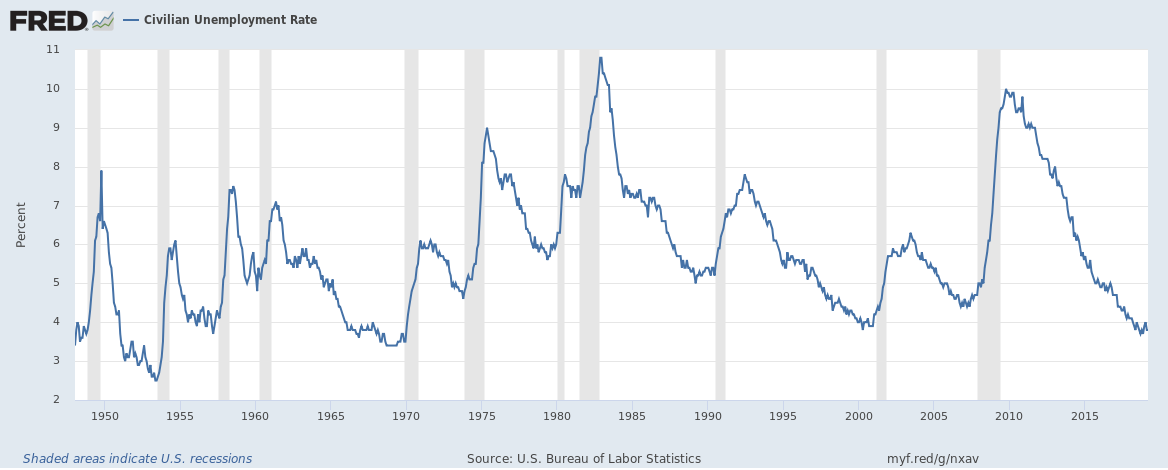

Analogies Between Economic Models and the Biology of Obesity

Layne Norton Discusses the Stephan Guyenet vs. Gary Taubes Debate (a Debate on Joe Rogan’s Podcast)

VIII. Debates about Particular Foods and about Exercise

Jason Fung: Dietary Fat is Innocent of the Charges Leveled Against It

Faye Flam: The Taboo on Dietary Fat is Grounded More in Puritanism than Science

Confirmation Bias in the Interpretation of New Evidence on Salt

Eggs May Be a Type of Food You Should Eat Sparingly, But Don't Blame Cholesterol Yet

Julia Belluz and Javier Zarracina: Why You'll Be Disappointed If You Are Exercising to Lose Weight, Explained with 60+ Studies (my retitling of the article this links to)

IX. Gary Taubes

X. Twitter Discussions

Putting the Perspective from Jason Fung's "The Obesity Code" into Practice

'Forget Calorie Counting. It's the Insulin Index, Stupid' in a Few Tweets

Debating 'Forget Calorie Counting; It's the Insulin Index, Stupid'

Analogies Between Economic Models and the Biology of Obesity

XI. On My Interest in Diet and Health

See the last section of "Five Books That Have Changed My Life" and the podcast "Miles Kimball Explains to Tracy Alloway and Joe Weisenthal Why Losing Weight Is Like Defeating Inflation." If you want to know how I got interested in diet and health and fighting obesity and a little more about my own experience with weight gain and weight loss, see “Diana Kimball: Listening Creates Possibilities” and my post "A Barycentric Autobiography. I defend the ability of economists like me to make a contribution to understanding diet and health in “On the Epistemology of Diet and Health: Miles Refuses to `Stay in His Lane’.”