William Pearse Interviews Eight Economics Bloggers on Whether You Should Be Blogging →

I am glad to be in the company of John Cochrane, Diane Coyle, Leigh Caldwell, Robin Hanson, Timothy Taylor, Jim Hamilton, and Antonio Fatas in this distillation from our answers to a set of questions about blogging.

David Ludwig, Walter Willett, Jeff Volek and Marian Neuhouser: Controversies and Consensus on Fat vs. Carbs

David Ludwig is not a fan of lowfat diets. He is the author of Always Hungry, which includes this in its Amazon summary:

Low-fat diets work against you, by triggering fat cells to hoard more calories for themselves, leaving too few for the rest of the body. This "hungry fat" sets off a dangerous chain reaction that leaves you feeling ravenous as your metabolism slows down. Cutting calories only makes the situation worse-creating a battle between mind and metabolism that we're destined to lose.

But to write the November 16, 2018 Science article “Dietary fat: From foe to friend?” he teamed up nutrition researchers with different views. Together, they tried to identify areas of disagreement and areas of agreement. Let me briefly discuss the seven areas of agreement they found.

Both lowcarb and lowfat diets can work well. As I write in “Why a Low-Insulin-Index Diet Isn't Exactly a 'Lowcarb' Diet,” different kinds of carbohydrates differ dramatically in whether or not they cause insulin spikes. Lettuce, spinach, kale, broccoli, cauliflower and brussel sprouts technically have a lot of carbohydrates in them, but they are free of the easily-digestible carbs that turn into blood sugar quickly, which in turn causes a spike in insulin. A highcarb diet with little or no sugar and little or no processed food is a very different thing from what many people think of as a highcarb diet.

Saturated fats are bad. I think the jury is still out on this. Saturated fats are especially common in foods from animal sources, and foods from animal sources could have a lot of other problems. For example, I have been sympathetic to the idea that animal protein is a cancer risk. (See “Meat Is Amazingly Nutritious—But Is It Amazingly Nutritious for Cancer Cells, Too?”) And the most common type of milk in the supermarket has what appears to be a particularly dangerous protein in it. (See “Exorcising the Devil in the Milk.”) A good way to test how bad saturated fats are without results confounded by other problems in animal foods would be to have everyone in a clinical trial eat a vegan diet (as similar in other ways as possible), with half of them eating a diet with a lot of coconut milk in it, the other half avoiding all plant foods that have a lot of saturated fat.

Avoid sugar, refined grains and potatoes. Yes!

Lowcarb, high fat diets may be good for people with insulin resistance. Yes. And a large share of all Americans have insulin resistance to some degree.

Ketogenic diets may be helpful for people with special problems. This is a pretty weak statement and hard to disagree with.

A lowcarb, high fat diet doesn’t have to have a lot of animal products or a lot of protein in it. Yes. I am not a vegan, but I only eat a modest amount of animal products. (See “My Giant Salad,” “Our Delusions about 'Healthy' Snacks—Nuts to That!” “Intense Dark Chocolate: A Review,” “In Praise of Avocados” and “Eating on the Road.)

We should invest more in nutritional research. Here I love this sentence from the article: “Currently, the United States invests a fraction of a cent on nutrition research for each dollar spent on treatment of diet-related chronic disease.” Two weeks ago, I gave my own version of this argument:

To distinguish between different hypotheses, we need a lot more dietary clinical trials. Given the trillions of dollars worth of harm from the typical American diet (a number I discuss in “The Heavy Non-Health Consequences of Heaviness”), our nation is being penny-wise and pound foolish by not spending more money on dietary clinical trials to figure out what is healthy and what isn’t. Email correspondence with the head of one major study (see “Why a Low-Insulin-Index Diet Isn't Exactly a 'Lowcarb' Diet”) suggested that a reasonably high-quality dietary clinical trial (by current standards), might cost about $8 million. Thus, even without any government assistance, any billionaire could likely do trillions and trillions of dollars worth of good for the world by funding over time the equivalent of 100 dietary clinical trials of that size to test hypotheses about diet and health like those I discuss on this blog (and still have $200 million left over to live on). Some of this is happening, but much, much more needs to be done.

What is missing from this article is any discussion of the timing of eating. Fasting—periods of time with no food—is looking very promising in many studies as a way to gain many health benefits. (See “Stop Counting Calories; It's the Clock that Counts” and “Lisa Drayer: Is Fasting the Fountain of Youth?”) Even among readers of this blog, I have the sense that many think my main recommendation is to eat low on the insulin index. There is some truth to this, as you can see from “Obesity Is Always and Everywhere an Insulin Phenomenon” and “Forget Calorie Counting; It's the Insulin Index, Stupid.” But I consider fasting as the most important measure I would recommend for improving health through diet. Indeed, fasting is so important that I consider the single greatest benefit of a low-insulin-index diet to be that—in my experience and that of others I know—it makes fasting much easier. That is a claim I would love to have subjected a clinical trial.

On fasting, let me try to pull you away from some weirdnesses out there. In “Biohacking: Nutrition as Technology” I write:

Fasting doesn’t need any particular pattern. The environment of evolutionary adaptation for humans likely had a lot of random involuntary fasting. So we are likely to be designed for patternless fasting. The main thing is to (a) do enough total fasting and (b) fast for some reasonably long chunks of time, and (c) work up slowly to anything more than 24 hours so that you know your tolerance for fasting. That’s it. No particular pattern needed. Do a water-only fast (or allow unsweetened coffee and tea) when it is most convenient, which might be either when you are especially busy or when you have many distractions to keep your mind off of food (which could happen at the same time).

One sign of this weird, overly structured approach to fasting is the common phrase “intermittent fasting.” To me, the word “intermittent” here is redundant. If you don’t intersperse periods of eating food into your fasting, you will die! It is as simple as that. So I don’t think much of anyone is recommending non-intermittent fasting. Given that, one can call “intermittent fasting” just “fasting.”

I am not saying not to have any pattern to your fasting, but choose a pattern yourself based on what is convenient and requires the least willpower. I tend to fast on busy days when I have too many other things on my mind to think much about food anyway.

One thing I have been pleased at is that many clinical trials seem to be getting done about fasting. I would love to be involved as one of the scientists for one of those clinical trials. But in any case, we will know a lot more about the health effects of fasting ten years from now than we do today—both about safety and efficacy in improving health. To me, the evidence as it stands today makes fasting look like a good bet for your health.

Don’t miss my other posts on diet and health:

I. The Basics

Jason Fung's Single Best Weight Loss Tip: Don't Eat All the Time

What Steven Gundry's Book 'The Plant Paradox' Adds to the Principles of a Low-Insulin-Index Diet

II. Sugar as a Slow Poison

Best Health Guide: 10 Surprising Changes When You Quit Sugar

Heidi Turner, Michael Schwartz and Kristen Domonell on How Bad Sugar Is

Michael Lowe and Heidi Mitchell: Is Getting ‘Hangry’ Actually a Thing?

III. Anti-Cancer Eating

How Fasting Can Starve Cancer Cells, While Leaving Normal Cells Unharmed

Meat Is Amazingly Nutritious—But Is It Amazingly Nutritious for Cancer Cells, Too?

IV. Eating Tips

Using the Glycemic Index as a Supplement to the Insulin Index

Putting the Perspective from Jason Fung's "The Obesity Code" into Practice

Which Nonsugar Sweeteners are OK? An Insulin-Index Perspective

V. Calories In/Calories Out

VI. Wonkish

Framingham State Food Study: Lowcarb Diets Make Us Burn More Calories

Anthony Komaroff: The Microbiome and Risk for Obesity and Diabetes

Don't Tar Fasting by those of Normal or High Weight with the Brush of Anorexia

Carola Binder: The Obesity Code and Economists as General Practitioners

After Gastric Bypass Surgery, Insulin Goes Down Before Weight Loss has Time to Happen

A Low-Glycemic-Index Vegan Diet as a Moderately-Low-Insulin-Index Diet

Analogies Between Economic Models and the Biology of Obesity

VIII. Debates about Particular Foods and about Exercise

Jason Fung: Dietary Fat is Innocent of the Charges Leveled Against It

Faye Flam: The Taboo on Dietary Fat is Grounded More in Puritanism than Science

Confirmation Bias in the Interpretation of New Evidence on Salt

Julia Belluz and Javier Zarracina: Why You'll Be Disappointed If You Are Exercising to Lose Weight, Explained with 60+ Studies (my retitling of the article this links to)

IX. Gary Taubes

X. Twitter Discussions

Putting the Perspective from Jason Fung's "The Obesity Code" into Practice

'Forget Calorie Counting. It's the Insulin Index, Stupid' in a Few Tweets

Debating 'Forget Calorie Counting; It's the Insulin Index, Stupid'

Analogies Between Economic Models and the Biology of Obesity

XI. On My Interest in Diet and Health

See the last section of "Five Books That Have Changed My Life" and the podcast "Miles Kimball Explains to Tracy Alloway and Joe Weisenthal Why Losing Weight Is Like Defeating Inflation." If you want to know how I got interested in diet and health and fighting obesity and a little more about my own experience with weight gain and weight loss, see “Diana Kimball: Listening Creates Possibilities” and my post "A Barycentric Autobiography.

Nolan Gray and Brandon Fuller: A Red-State Take on a YIMBY Housing Bill →

“YIMBY” means “Yes, in my backyard,” and is the opposite of “NIMBY,” which stands for “Not in my backyard.”

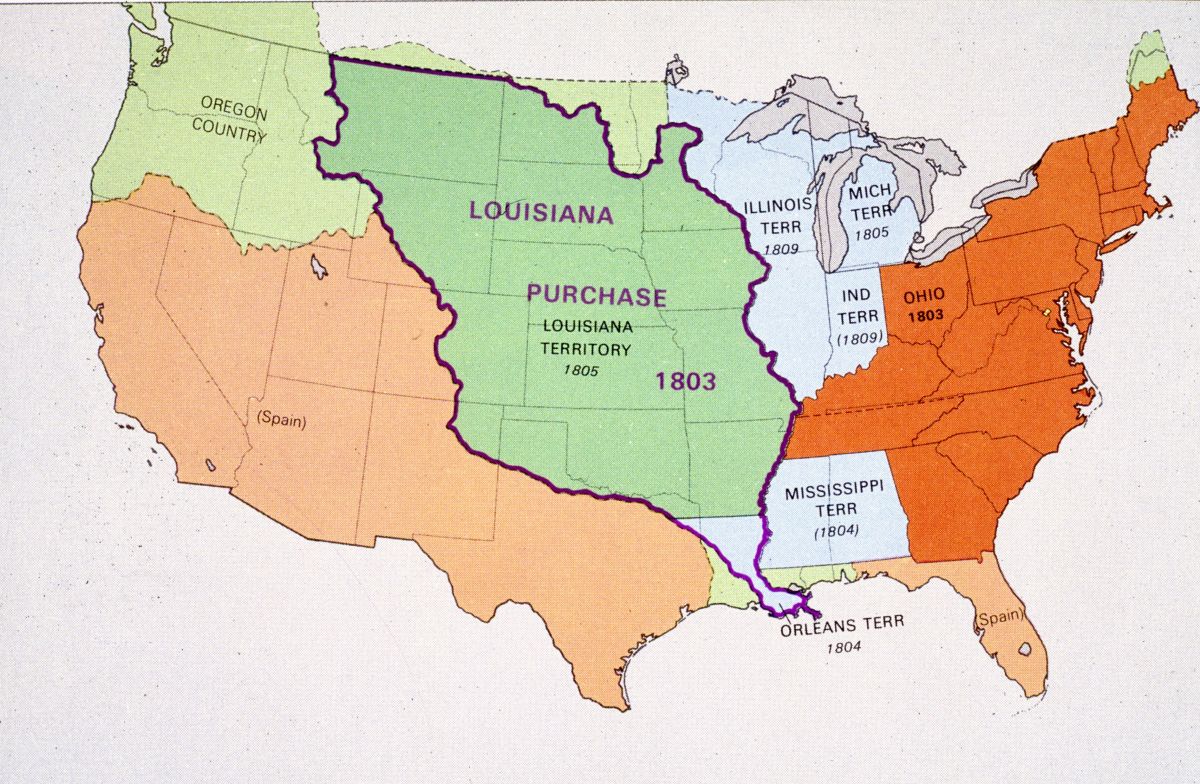

Getting Away with Doing Good

As I noted in “John Locke: Revolutions are Always Motivated by Misrule as Well as Procedural Violations,” in my experience, Department Chairs can get away with procedural violations as long as everyone agrees with what they are doing. On a larger stage, people didn’t get that upset with Thomas Jefferson for making the Lousiana purchase, even though that action arguably exceeded his constitutional powers.

John Locke, in Chapter XIV, “Of Prerogative,” of his 2d Treatise on Government: Of Civil Government explains that doing good for the people appropriately allows a ruler to bend the rules, while no constitutional provision can justify a ruler in doing harm to the people. Constitutional provisions come into their own only when the people are sorely divided about whether a measure is good for them or not. Here is how John Locke makes the case:

§. 159. WHERE the legislative and executive power are in distinct hands, (as they are in all moderated monarchies, and well-framed governments) there the good of the society requires, that several things should be left to the discretion of him that has the executive power: for the legislators not being able to foresee, and provide by laws, for all that may be useful to the community, the executor of the laws, having the power in his hands, has by the common law of nature a right to make use of it for the good of the society, in many cases, where the municipal law has given no direction, till the legislative can conveniently be assembled to provide for it. Many things there are, which the law can by no means provide for; and those must necessarily be left to the discretion of him that has the executive power in his hands, to be ordered by him as the public good and advantage shall require: nay, it is fit that the laws themselves should in some cases give way to the executive power, or rather to this fundamental law of nature and government, viz. That as much as may be all the members of the society are to be preserved: for since many accidents may happen, wherein a strict and rigid observation of the laws may do harm; (as not to pull down an innocent man’s house to stop the fire, when the next to it is burning) and a man may come sometimes within the reach of the law, which makes no distinction of persons, by an action that may deserve reward and pardon; ’tis fit the ruler should have a power, in many cases, to mitigate the severity of the law, and pardon some offenders: for the end of government being the preservation of all, as much as may be, even the guilty are to be spared, where it can prove no prejudice to the innocent.

§. 160. This power to act according to discretion, for the public good, without the prescription of the law, and sometimes even against it, is that which is called prerogative:for since in some governments the law-making power is not always in being, and is usually too numerous, and so too slow, for the dispatch requisite to execution; and because also it is impossible to foresee, and so by laws to provide for, all accidents and necessities that may concern the public, or to make such laws as will do no harm, if they are executed with an inflexible rigour, on all occasions, and upon all persons that may come in their way; therefore there is a latitude left to the executive power, to do many things of choice which the laws do not prescribe.

§. 161. This power, whilst employed for the benefit of the community, and suitably to the trust and ends of the government, is undoubted prerogative, and never is questioned: for the people are very seldom or never scrupulous or nice in the point; they are far from examining prerogative, whilst it is in any tolerable degree employed for the use it was meant, that is, for the good of the people, and not manifestly against it; but if there comes to be a question between the executive power and the people, about a thing claimed as a prerogative; the tendency of the exercise of such prerogative to the good or hurt of the people, will easily decide that question.

§. 162. It is easy to conceive, that in the infancy of governments, when commonwealths differed little from families in number of people, they differed from them too but little in number of laws: and the governors, being as the fathers of them, watching over them for their good, the government was almost all prerogative. A few established laws served the turn, and the discretion and care of the ruler supplied the rest. But when mistake or flattery prevailed with weak princes to make use of this power for private ends of their own, and not for the public good, the people were fain by express laws to get prerogative determined in those points wherein they found disadvantage from it: and thus declared limitations of prerogative were by the people found necessary in cases which they and their ancestors had left, in the utmost latitude, to the wisdom of those princes who made no other but a right use of it, that is, for the good of their people. 4

§. 163. And therefore they have a very wrong notion of government, who say, that the people have incroached upon the prerogative, when they have got any part of it to be defined by positive laws: for in so doing they have not pulled from the prince any thing that of right belonged to him, but only declared, that that power which they indefinitely left in his or his ancestors’ hands, to be exercised for their good, was not a thing which they intended him when he used it otherwise: for the end of government being the good of the community, whatsoever alterations are made in it, tending to that end, cannot be an incroachment upon any body, since no body in government can have a right tending to any other end: and those only are incroachments which prejudice or hinder the public good. Those who say otherwise, speak as if the prince had a distinct and separate interest from the good of the community, and was not made for it; the root and source from which spring almost all those evils and disorders which happen in kingly governments. And indeed, if that be so, the people under his government are not a society of rational creatures, entered into a community for their mutual good; they are not such as have set rulers over themselves, to guard, and promote that good; but are to be looked on as an herd of inferior creatures under the dominion of a master, who keeps them and works them for his own pleasure or profit. If men were so void of reason, and brutish, as to enter into society upon such terms, prerogative might indeed be, what some men would have it, an arbitrary power to do things hurtful to the people.

§. 164. But since a rational creature cannot be supposed, when free, to put himself into subjection to another, for his own harm; (though, where he finds a good and wise ruler, he may not perhaps think it either necessary or useful to set precise bounds to his power in all things) prerogative can be nothing but the people’s permitting their rulers to do several things, of their own free choice, where the law was silent, and sometimes too against the direct letter of the law, for the public good; and their acquiescing in it when so done: for as a good prince, who is mindful of the trust put into his hands, and careful of the good of his people, cannot have too much prerogative, that is, power to do good; so a weak and ill prince, who would claim that power which his predecessors exercised without the direction of the law, as a prerogative belonging to him by right of his office, which he may exercise at his pleasure, to make or promote an interest distinct from that of the public, gives the people an occasion to claim their right, and limit that power, which, whilst it was exercised for their good, they were content should be tacitly allowed.

§. 165. And therefore he that will look into the History of England, will find, that prerogative was always largest in the hands of our wisest and best princes; because the people, observing the whole tendency of their actions to be the public good, contested not what was done without law to that end: or, if any human frailty or mistake (for princes are but men, made as others) appeared in some small declinations from that end; yet it was visible, the main of their conduct tended to nothing but the care of the public. The people therefore, finding reason to be satisfied with these princes, whenever they acted without, or contrary to the letter of the law, acquiesced in what they did, and, without the least complaint, let them enlarge their prerogative as they pleased, judging rightly, that they did nothing herein to the prejudice of their laws, since they acted conformable to the foundation and end of all laws, the public good.

§. 166. Such godlike princes indeed had some title to arbitrary power by that argument, that would prove absolute monarchy the best government, as that which God himself governs the universe by; because such kings partake of his wisdom and goodness. Upon this is founded that saying, That the reigns of good princes have been always most dangerous to the liberties of their people: for when their successors, managing the government with different thoughts, would draw the actions of those good rulers into precedent, and make them the standard of their prerogative: as if what had been done only for the good of the people was a right in them to do, for the harm of the people, if they so pleased; it has often occasioned contest, and sometimes public disorders, before the people could recover their original right, and get that to be declared not to be prerogative, which truly was never so; since it is impossible that any body in the society should ever have a right to do the people harm; though it be very possible, and reasonable, that the people should not go about to set any bounds to the prerogative of those kings, or rulers, who themselves transgressed not the bounds of the public good: for prerogative is nothing but the power of doing public good without a rule.

§. 167. The power of calling parliaments in England, as to precise time, place, and duration, is certainly a prerogative of the king, but still with this trust, that it shall be made use of for the good of the nation, as the exigencies of the times, and variety of occasions, shall require; for it being impossible to foresee which should always be the fittest place for them to assemble in, and what the best season; the choice of these was left with the executive power, as might be most subservient to the public good, and best suit the ends of parliaments.

§. 168. The old question will be asked in this matter of prerogative, But who shall be judge when this power is made a right use of? I answer: between an executive power in being, with such a prerogative, and a legislative that depends upon his will for their convening, there can be no judge on earth; as there can be none between the legislative and the people, should either the executive, or the legislative, when they have got the power in their hands, design, or go about to enslave or destroy them. The people have no other remedy in this, as in all other cases where they have no judge on earth, but to appeal to heaven: for the rulers, in such attempts, exercising a power the people never put into their hands, (who can never be supposed to consent that any body should rule over them for their harm) do that which they have not a right to do. And where the body of the people, or any single man, is deprived of their right, or is under the exercise of a power without right, and have no appeal on earth, then they have a liberty to appeal to heaven, whenever they judge the cause of sufficient moment. And therefore, though the people cannot be judge, so as to have, by the constitution of that society, any superior power, to determine and give effective sentence in the case; yet they have, by a law antecedent and paramount to all positive laws of men, reserved that ultimate determination to themselves which belongs to all mankind, where there lies no appeal on earth, viz. to judge, whether they have just cause to make their appeal to heaven. And this judgment they cannot part with, it being out of a man’s power so to submit himself to another, as to give him a liberty to destroy him; God and nature never allowing a man so to abandon himself, as to neglect his own preservation: and since he cannot take away his own life, neither can he give another power to take it. Nor let any one think, this lays a perpetual foundation for disorder: for this operates not, till the inconveniency is so great, that the majority feel it, and are weary of it, and find a necessity to have it amended. But this the executive power, or wise princes, never need come in the danger of: and it is the thing, of all others, they have most need to avoid, as of all others the most perilous.

I find John Locke’s emphasis on the principle that the government is meant to benefit its people refreshing. Constitutional provisions are in service to the end of benefitting people.

The great revolutions in government over time have been in expanding the set of people who count—roughly speaking, first the nobility, then rich men, then poor men of favored ethnic backgrounds, then women, then others of disfavored ethnic backgrounds, and finally those within all of those groups who had not counted because they had been considered deviant in some way. Now the great battle is whether other human beings who, because they were born elsewhere and so do not have citizenship count.

Here the fact that many of these people would gladly take on all the duties of citizenship is highly relevant. Indeed, many would gladly take on all the duties of citizenship plus a host of additional requirements, as long as those requirements were humanly possible for them to meet. To me, it seems much better to add stiff requirements that new entrants to our republic need to meet (but most have the ability to meet) than to consign them irredeemably to the relative nonpersonhood of noncitizenship. Saying everyone has their own nation already is not a great answer when nations differ so widely in quality. It is better for those of us who are already citizens of a rich and relatively well-run nation to drive a hard bargain than to simply exclude people without giving them any recourse.

Of course, showing care for those who are noncitizens is likely to incite jealousy from some of the worst off of those who already are citizens, and those who feel they have been on a downward trajectory. There is an enlightened answer to that: care about them and vigorously pursue policies that benefit them as well. The opposite—an elite that relegates all of those who do not have the lifestyle and views of the elite to the category of those who don’t count—is disgusting and repellent, but common.

For links to other John Locke posts, see these John Locke aggregator posts:

Andrew Biggs and Miles Kimball Debate Retirement Savings Policy

My Bloomberg Opinion column “Fight the Backlash Against Retirement Saving Nudges: Everyone Benefits When People Save More for Old Age” takes issue with a piece by Andrew Biggs of the American Enterprise Institute. A few days after my column came out, Michael Newman from Bloomberg Opinion invited Andrew Biggs to respond. That led to this dialogue by email (lightly edited). I am grateful to Andrew Biggs for permission to publish this discussion.

Andrew: The disagreement may be a bit narrow, in that I’m not really against auto-enrollment as a general policy. For middle-income people who do need to save but might forget to enroll in their 401(k), it’s a good idea.

My issue is that applying auto-enrollment to low earners, as with the states’ proposals for auto-IRA plans, could have real downsides in that you’re pushing people to save when they may not really need to and when the costs to reduced take-home pay could be more substantial. Kind of wonky, I admit! But given the momentum behind the state plans, I think it’s worth looking at.

Miles: There may not be a lot of disagreement. I agree with Andrew that pushing low-income earners to save for retirement isn't needed since for them Social Security looks pretty good compared to their usual income. However in my Bloomberg piece, though I am not fully explicit on this, I take the view that if a retirement saving plan allows people to borrow from it to make down payments on cars and houses, the automatic enrollment may serve a useful role in helping them put together that down payment. What this means, though, is that the lower income the earner, the more it should be structured with the idea that the ability to take loans from one's own "retirement saving account" is the main benefit, not the retirement saving itself.

There is no question that all of this only makes sense from a behavioral economics point of view. If everyone were a rational optimizer, none of this would needed and none of it would even work, since people would just opt out whenever that was optimal. There are two departures from being a rational optimizer in play: information processing costs (of which "forgetting" is one, but only one) and internal conflict. In an internal conflict between parts of oneself, automatic enrollment can give the edge to the part of oneself that wants to save more.

Andrew: I realized my first email didn't really get at where I disagreed with your piece. For the average employee I think it's arguable that auto-enrollment worked well, depending on your take on mortgage debt. But at the low end the additional consumer/auto debt was substantially more than employee contributions and almost equal to combined employee/employer contributions. I don't find an easy benign explanation for this. That's the main issue I have.

On top of that, I'm not sure whether additional mortgage debt is due to the ability to borrow against TSP assets, to lower down-payments (maybe due to lower liquidity) or maybe just to excess optimism ("I'm rich!"). I don't know if the data exist to really answer that question, though in theory some admin data on borrowing against TSP balances could help.

Miles: The way I read the data is based on the idea that those who are financially strapped usually pay the minimum down payment. If that is the case, owing more money on a car or house would have to represent either

a higher total purchase price,

becoming able to borrow for the car or house rather than having to pay in cash, or

less plausibly, the required down payment becoming less.

The only plausible reasons for the value of houses and cars they purchase to be higher are either that they realize they are richer because of the match or that the ability to borrow from the thrift savings plan makes it easier to put together a bigger down payment. Every one of these possibilities reflects the set of choices these individuals have for buying houses and cars expanding.

The story where forced retirement saving makes it harder to put together a down payment so they make a smaller down payment depends on people who are not in the retirement savings plan making more than a minimum down payment. That seems unlikely to me.

Expanding the range of choices low-income individuals have for buying houses and cars could be either a good thing or a bad thing. It might have been a bad thing that the Thrift Savings Plan expanded the range of options for low-income individuals to buy houses or cars. I wouldn't jump to that conclusion. After all, owning a house can be cheaper than renting and for many people a car that won't break down can be crucial for reliably getting to work from areas with low house prices or rents. But if expanding choices for buying houses or cars is a bad thing for these low-income folks, it can be remedied by fixing the design of the Thrift Savings Plan. For example, if research suggested borrowing for a house was a good thing, but borrowing for a car was a bad thing, modify the rules so they can borrow for a house but not for a car.

By the way, Congress is working on a 401(k) reform package that looks mostly sensible to me. I wonder about your thoughts on that.

Andrew: I have a piece in today’s Washington Post looking at the state plans. My three main points are that there’s not a ton of evidence that low-income Americans are undersaving for retirement; this doesn’t mean auto-IRAs are a bad idea, but it does mean that the plans’ downsides should probably be given greater weight than if there were a huge undersaving problem to solve. Second, I cite the Beshears et al paper on the debt issue, in particular for less-educated workers. And third, the states’ haven’t given much (or any) thought to how the auto-IRAs will affect eligibility for means-tested transfer programs. It doesn’t take much additional assets or income to be disqualified from TANF, SNAP, Section 8 or Medicaid. Beneficiaries may have to spend down their accounts until they regain eligibility, which means state budgets may benefit more than the poor will.

In terms of the savings/debt issues you raise, it would great to have more data. I wish some of the states setting up auto-IRA plans would do as Seattle did with the minimum wage and design a study from the get-go. I’m not confident on that. It also would be great if Beshears et al continued to track these federal employees over time; I don’t know whether they’re able to do that.

But sticking to what we know so far, I see the results for the less-educated auto-enrollees as a problem. Consider that that increase in consumer debt alone offsets almost 2/3rds of employee contributions. It’s hard to find a benign explanation for that. Maybe if it’s a wealth effect then the results will be smaller for auto-IRAs where there’s no employer match, but still I find that troubling. Add auto loans and you’re offsetting 82% of total contributions and 175% of employee contributions. Maybe they’re buying bigger cars, maybe making lower down payments (or both!) An auto is more consumption than asset, as I see it. In both these cases, I don’t think the ability to borrow against TSP assets plays into things.

Maybe, as you say, the higher auto/home loan balances are due to a wealth effect. But the employee is only truly richer by the amount of the employer match, which is under 4% of pay, whereas additional auto/home loan balances are equal to about 20% of pay. I’d like to see how these evolve over time, but if the principal result is workers borrowing against their new retirement savings to buy bigger/better homes and cars, that’s kind of underwhelming.

Miles: When you say “increase in consumer debt alone offsets almost 2/3rds of employee contributions,” I notice I have a different reading. I read the paper as saying that by the time the data were cut by income level there wasn't much precision to know what was happening with consumer debt. Certainly there could be a problem, but there is at least one benign possible explanation: statistical chance in the data.

I want to be clear that my story about more expensive houses and cars isn't primarily about a wealth effect; it is primarily about being able to get together a bigger down payment and therefore being able to get a car or house loan on a more expensive car or house. Even without being any richer, they would have liked to borrow more for a house or car but weren't allowed to without the bigger down payment. Having a little more money for a down payment allows one to borrow quite a bit more. It isn't clear that this is a bad thing, though it might be.

Andrew: If you saw the Post piece, I make three points: first, there’s solid evidence (see Bee and Mitchell and Brady et al) that most retirees, including lower income ones, have replacement rates above what financial advisors typically recommend. So there’s a hurdle of justifying the need to save more that’s usually ignored. Second, there’s the issue of how the account balances interact with means-tested benefits; that could be a real issue, which neither the states nor the federal government have looked at. And third, there’s the issue of whether auto-IRA accounts lead to higher net saving.

On the last, obviously we’d all like more and better data – in particular knowledge of the actual assets the households hold and how savings and debts evolve over time. The Beshears et al paper only had data through a bit over four years, which may not be enough time to really tell, but still I think it’s important that they released what they had.

I don’t really buy the argument in the paper that larger homes should be considered a form of saving that offsets the higher debt. Obviously a home is an asset, but it’s also a consumption good that carries a lot of tax/maintenance costs along the way. Moreover, many/most retirees don’t move out of their homes, so mostly what they’ve got is simply a larger home. And if you look at work by Mitchell and Lasardi and others, they consider households carrying more debt into retirement a major (maybe the major) issue with retirement income adequacy.

You think (and probably to a degree you’re right) that the higher savings are making it easier to employees to make a home down payment, so maybe they’re able to buy rather than rent or to buy a bigger home. Beshears analyzed federal workers, most of whom own homes (even among those with less than a high school education) so I’m not sure on that. What I’d like to see is not simply changes to TSP contributions over time, but some measure of account balances to see if people are borrowing against those funds. I know I did in making my first home purchase, but I just don’t know for sure.

In terms of less educated workers, the degree of debt increase just seems too large to be helpful. Debt rises by three times more than total TSP contributions and seven times more than employee-only contributions (perhaps relevant, given that auto-IRAs can’t have an employer match). Moreover, much of that seems to be auto and consumer debt, where the housing-as-asset argument doesn’t apply.

I’m not exactly against auto-IRAs; on one had, we know that saving through work is more effective than setting up IRAs on our own, but we also know there’s leakage as employees shift between employers. Auto-IRAs get around that. At the same time, too many of the states seem in rah-rah mode rather than really weighing the issues and working out practical problems like means-tested benefits. So I think there’s still work to be done.

Miles: Your point about interaction with safety-net programs is a good one. And I agree that one should question whether or not retirement savings plans should be designed to also help people get into bigger houses. That points to the broader issue that the precise design of retirement savings programs matters a lot. And, as you say, if low-income folks have adequate retirement savings (in part because social security looks pretty good to them compared to what they are living on before retirement), the side effects from design details can be a big deal compared to any benefit from encouraging extra retirement saving. If those side effects are good, that case should be made. If the side effects are bad from other design features, that could weigh heavily.

A Low-Glycemic-Index Vegan Diet as a Moderately-Low-Insulin-Index Diet

If a clinical trial shows a diet has benefits relative to what people normally eat, it can be hard to know which of the many dimensions in which that diet is different is doing the trick. (See “Hints for Healthy Eating from the Nurse's Health Study” for examples of how carefully one must parse the typical kind of evidence.) The GEICO Study analyzed by Ulka Agarwal, Suruchi Mishra, Jia Xu, Susan Levin, Joseph Gonzales, and Neal D. Barnard in “A Multicenter Randomized Controlled Trial of a Nutrition Intervention Program in a Multiethnic Adult Population in the Corporate Setting Reduces Depression and Anxiety and Improves Quality of Life: The GEICO Study” is a case in point. Many, many diets are better than what Americans normally eat. I have advocated on this blog a low-insulin-index diet. (See “Forget Calorie Counting; It's the Insulin Index, Stupid” and “Obesity Is Always and Everywhere an Insulin Phenomenon.”) In the case of the GEICO study, I want to argue that its low-glycemic-index vegan diet would have had a moderately low insulin index—much lower than the typical American diet. The reason is that it isn’t just carbs that stimulate insulin: certain proteins stimulate insulin as well. So one place where the glycemic index differs most markedly from the insulin index is that meat and skim milk are higher on the insulin index than one would predict from where they are on the glycemic index. So for those who don’t know about the insulin index, going vegan protects them from some of the errors they would make by looking at the glycemic index.

It is worth trying to parse the results of the GEICO Study, because they found some evidence of reduced depression and anxiety and improved productivity from instructing people in this diet. A major part of the instruction was teaching people about the glycemic index. Could lower insulin levels lead to a better mood and increased productivity? I think the answer is yes. Insulin spikes can lower blood sugar levels below normal. Low blood sugar levels can make people feel lousy and low in energy. (They didn’t measure anger. Low blood sugar levels probably increase the incidence of anger. I wrote about this in “How Sugar Makes People Hangry” and “Michael Lowe and Heidi Mitchell: Is Getting ‘Hangry’ Actually a Thing?”)

On particular, testable—but as yet untested—claim I want to make is that the “lowfat” dimension of the diet was not important to any of the good effects. It is more likely that the vegan aspect of the diet was helpful than the lowfat aspect. But that should be tested too. Adding some omega 3 eggs, goat cheese or whole A2 milk to the diet might not hurt any of the results they mention. (On these particular choices, see “What Steven Gundry's Book 'The Plant Paradox' Adds to the Principles of a Low-Insulin-Index Diet” and “Exorcising the Devil in the Milk.”)

Where I worry about animal products, it is about the effect that animal protein might have in helping to promote cancer. Cancer cells are typically damaged metabolically, but some of the easiest chemicals to metabolize—which even cancer cells can manage to get sustenance from—are sugar and some of the amino acids that are abundant in animal protein. See:

The dangers from animal protein—both in raising insulin, and possibly promoting cancer—are a big confounding factor in people’s reading of the evidence on how healthy animal fat is. People usually don’t eat a lot of animal fat without also eating a lot of animal protein. The one big exception is butter, which people tend to eat with bread, which is very high on the insulin index. So as far as much of the evidence goes, animal fat might be OK if one avoids all the things that are usually eaten with animal fat. It would be very interesting to go through all the evidence against animal fat with this in mind.

For someone like me, focused on insulin, it would be great to have much more measurement of the effects of different interventions on insulin. Then all effects should be parceled into the part of the effect that would be expected from the change in insulin levels (after correcting for measurement error in measuring the insulin levels) and the effects that go beyond what one could expect from the change in insulin levels. The most expensive part of trials is getting people to eat differently. Adding measurement of insulin levels is a modest expense by comparison. And if it is measured, it should be a big part of the statistical analysis.

The bottom line is that the GEICO Study seems consistent with the hypothesis that a lower average insulin level from low-insulin-index eating has benefits. Of course, it is also consistent with many other hypotheses! To distinguish between different hypotheses, we need a lot more dietary clinical trials. Given the trillions of dollars worth of harm from the typical American diet (a number I discuss in “The Heavy Non-Health Consequences of Heaviness”), our nation is being penny-wise and pound foolish by not spending more money on dietary clinical trials to figure out what is healthy and what isn’t. Email correspondence with the head of one major study (see “Why a Low-Insulin-Index Diet Isn't Exactly a 'Lowcarb' Diet”) suggested that a reasonably high-quality dietary clinical trial (by current standards), might cost about $8 million. Thus, even without any government assistance, any billionaire could likely do trillions and trillions of dollars worth of good for the world by funding over time the equivalent of 100 dietary clinical trials of that size to test hypotheses about diet and health like those I discuss on this blog (and still have $200 million left over to live on). Some of this is happening, but much, much more needs to be done.

Don’t miss my other posts on diet and health:

I. The Basics

Jason Fung's Single Best Weight Loss Tip: Don't Eat All the Time

What Steven Gundry's Book 'The Plant Paradox' Adds to the Principles of a Low-Insulin-Index Diet

II. Sugar as a Slow Poison

Best Health Guide: 10 Surprising Changes When You Quit Sugar

Heidi Turner, Michael Schwartz and Kristen Domonell on How Bad Sugar Is

Michael Lowe and Heidi Mitchell: Is Getting ‘Hangry’ Actually a Thing?

III. Anti-Cancer Eating

How Fasting Can Starve Cancer Cells, While Leaving Normal Cells Unharmed

Meat Is Amazingly Nutritious—But Is It Amazingly Nutritious for Cancer Cells, Too?

IV. Eating Tips

Using the Glycemic Index as a Supplement to the Insulin Index

Putting the Perspective from Jason Fung's "The Obesity Code" into Practice

Which Nonsugar Sweeteners are OK? An Insulin-Index Perspective

V. Calories In/Calories Out

VI. Wonkish

Framingham State Food Study: Lowcarb Diets Make Us Burn More Calories

Anthony Komaroff: The Microbiome and Risk for Obesity and Diabetes

Don't Tar Fasting by those of Normal or High Weight with the Brush of Anorexia

Carola Binder: The Obesity Code and Economists as General Practitioners

After Gastric Bypass Surgery, Insulin Goes Down Before Weight Loss has Time to Happen

Analogies Between Economic Models and the Biology of Obesity

VIII. Debates about Particular Foods and about Exercise

Jason Fung: Dietary Fat is Innocent of the Charges Leveled Against It

Faye Flam: The Taboo on Dietary Fat is Grounded More in Puritanism than Science

Confirmation Bias in the Interpretation of New Evidence on Salt

Julia Belluz and Javier Zarracina: Why You'll Be Disappointed If You Are Exercising to Lose Weight, Explained with 60+ Studies (my retitling of the article this links to)

IX. Gary Taubes

X. Twitter Discussions

Putting the Perspective from Jason Fung's "The Obesity Code" into Practice

'Forget Calorie Counting. It's the Insulin Index, Stupid' in a Few Tweets

Debating 'Forget Calorie Counting; It's the Insulin Index, Stupid'

Analogies Between Economic Models and the Biology of Obesity

XI. On My Interest in Diet and Health

See the last section of "Five Books That Have Changed My Life" and the podcast "Miles Kimball Explains to Tracy Alloway and Joe Weisenthal Why Losing Weight Is Like Defeating Inflation." If you want to know how I got interested in diet and health and fighting obesity and a little more about my own experience with weight gain and weight loss, see “Diana Kimball: Listening Creates Possibilities” and my post "A Barycentric Autobiography.

John Bailey Jones on Intentional and Unintentional Bequests →

Hat tip to Daniel Arovas.

Maria Popova's 2019 Valentine's Day Post →

Don’t miss these Valentine’s Day posts by me—or the one by my wife, Gail:

Marriage 101 from 2014

Marriage 102 from 2017

Marriage—Not for the Faint of Heart by my wife Gail from 2018.

Marriage 103 from 2019

Bill and Melinda Gates's 2019 Newsletter →

This newsletter is quite thoughtful, and has an interesting graph about greenhouse emissions by sector.

Marriage 103

Link to the lyrics of “Saints and Angels”

Link to a video of “Saints and Angels” sung by its writer, Victoria Banks

Today is Valentine’s Day. I want to follow up these previous Valentine’s day posts:

Marriage 101 from 2014

Marriage 102 from 2017

Marriage—Not for the Faint of Heart by my wife Gail from 2018.

I have a simple theme. The success of a marriage depends to an important extent on both partners investing in that marriage. And how much each partner invests in a marriage is likely to depend a lot on how long each of them thinks the marriage will last. So there is self-fulfilling prophecy aspect to marriages—or what economists called “multiple equilibrium”: if two people think their marriage will last, it is more likely to actually last; if they think it won’t last, it is less likely to last.

The song “Saints and Angels” above, written by Victoria Banks and best known as performed by Sara Evans makes the strategy for the better of the two equilibria clear:

We're only human baby

We walk on broken ground …

We fall from grace

Forget we can fly

But through all the tears that we cry

We'll survive

… We're just two tarnished hearts

But in each others arms

We become saints and angels

…

I love you when you hold me

And when you turn away

I love you still

And I'm not afraid

'Cause I know you feel the same way

And you'll stay

…

These feet of clay

They will not stray

Beyond the effects of both partners investing in the relationship, commitment to staying may have an even deeper effect. Because reproduction is so central to evolution, human beings may well have specific adaptations for two different possible strategies in a relationship: the strategy appropriate for romantic relationships expected to be short-lived and the strategy appropriate for romantic relationships expected to be long-lived. What is the appropriate strategy if the relationship is expected to be lifelong on the part of both partners? In that case, the fact that descendants will be shared means that the objective function evolution has for the two members of such a longterm relationship will be very similar. There is some gap in evolutionary interests even in such a long-lived relationship: someone is bound to die first, and the evolutionary interest is greater for blood relatives who are not descendants—parents, sisters, brother, nephews, nieces, etc.—than for in-laws. But the high degree of concordance of evolutionary interests for a pair that both expect a lifelong relationship should mean that fully expecting a lifelong relationship should help kick highly cooperative adaptations into gear. If these highly cooperative adaptations can be kicked into gear, living and striving side by side with someone who is pulling in the same direction is a very rewarding experience!

Of course, things aren’t quite that simple, but where interests continue to differ, reciprocity, love and empathetic understanding can help make up the difference.

Economists use the unromantic sounding term “relationship-specific capital” for what one gets from investing in a relationship. Besides shared experiences and shared loved ones beyond the couple, one important type of relationship-specific capital is learning which battles to fight and which battles to avoid. Some of the content of what one can predict about what one’s partner will do or how one’s partner will react in any given situation can be frustrating. But being able to predict it is a lot better than having it come as a surprise! There is often a path to avoiding bad interactions and a path to seeking out good interactions. Many times early on in my marriage, I wished I could rewind time ten seconds and try a different tack. I couldn’t do that then, but in our 34+ years of marriage, a similar situation has often come up later on, in which I could indeed take a different tack.

Here is the bottom line: there are indeed marriages so damaging to at least one of the partners that the marriage should be broken apart. But assuming the partners begin the relationship by marrying someone of a gender they are attracted to, it is good to set expectations for the two in the relationship that both will be very, very slow to break apart the marriage for anything less heavy, say, than adultery by the other partner, physical abuse, felonies, or prolonged verbal and emotional abuse. As long as there is still good will and good intent on both sides, even big hairy arguments can often be worked through, and reruns of those arguments moderated.

For me, it is not a hard judgment to make that the most recent year in our marriage has been the best. I hope that continues to be true for the rest of our life together!

Adam Tooze Demythologizes Bretton Woods →

The title of this post is a link to Adam Tooze’s essay. Hat tip to John L. Davidson. You can see my proposal for changing the international economic order in “Alexander Trentin Interviews Miles Kimball about Establishing an International Capital Flow Framework.”

Biohacking: Nutrition as Technology

Many of the ideas on diet and health that I have written about here on this blog have attracted the attention of Silicon Valley companies. (That is cousin causality, not any causal influence flowing from my blog!) I wanted to give my reactions to various things Amanda Mull reports are on the market in her October 30, 2018 Atlantic article “The Harder, Better, Faster, Stronger Language of Dieting.”

Let me begin by saying that I find it a very congenial perspective to think of what I eat as a practical question without any big moral dimension beyond the idea that extending one’s life and improving one’s health might have some positive spillovers on other people. (By contrast, getting accurate information and useful perspectives to people about how they might extend their own lives and improve their health has a strong moral dimension. And intentionally obfuscating evidence about diet and health—say, in order to uphold sales of a product—is reprehensible to the highest degree.) So I find this that Amanda describes a positive development:

Dieting is no longer a necessary problem of vanity, as it has been historically termed, but a problem of knowledge and efficiency—a rhetorical shift with broad implications for how people think of themselves. Where bodies might have previously been idealized as personal temples, they’re now just another device to be managed, and one whose use people are expected to master. We’re optimizing our performances instead of watching our figure, biohacking our personal ecosystem instead of eating salads.

Amanda makes the point that this way of looking at things is especially important to men, but it seems to me likely to be helpful to women as well. If not, I would like someone to help me understand why not. The way dieting has been sold to women sounds pretty alienating to me, even if it has been successful in manipulating many women. As Amanda writes:

The diet industry’s modern history in America is feminized, which until recently left men as a relatively untapped potential market. “Gender contamination,” as the Harvard researcher Jill Avery coined it, is when a product or idea becomes so female-coded that men are no longer willing to engage with it. The classic example of this phenomenon is diet soda, and it’s no coincidence that gender contamination shows up most recognizably in the things people eat: The diet industry has always found its easiest prey among women, who are culturally primed to hone their appearance toward impossible ideals to demonstrate their social worth.

Note that the diet soda men shun probably hasn’t done much good for women either. There is little evidence that people’s weight goes down when they drink diet sodas. For some of why this might be, see “Which Nonsugar Sweeteners are OK? An Insulin-Index Perspective.”

Having discussed the new rhetorical angle for nutrition as technology, let’s talk about some specific things out there. Let me chop up one of Amanda’s paragraphs into bullet points and comment:

23andMe wants to help you eat and exercise according to your genetics.

I attend social science genetics conferences where the latest developments in human genetics in general are also talked about. There are some long-known disorders that depend only on a few genes, but aside from those, I don’t believe anyone who claims there is currently a measure based on tiny effects from many, many genes for people that could generate replicable results for diet and health. Basically, to get a reliable measure that would generate replicable results for a highly polygenic measure (based on many genes, each with a tiny effect), one would need very large samples of people with very good data on their diets. The best existing data sets are still not good enough. On the other hand, if you want the illusion of a result, a small sample is good for p-hacking. And with p-hacking, you could glom onto false positives of supposedly big effects of a few genes. My guess is that the services being sold are based on p-hacked science. But I would be glad to be told convincingly otherwise.

Bulletproof wants you to change your morning coffee routine to increase your work performance and reduce hunger.

In a phrase that predates any tradename, “bulletproof coffee” is coffee with butter melted in it. For coffee drinkers, bulletproof coffee is a great way to deal with a desire for something foodlike while still keeping one’s insulin levels low. (See “Obesity Is Always and Everywhere an Insulin Phenomenon” and “Forget Calorie Counting; It's the Insulin Index, Stupid.”) But you don’t have to pay someone extra to put the coffee and the butter together for you! And indeed, if you do it yourself, you can make it a bit healthier by using goat butter rather than cow butter. (See “Exorcising the Devil in the Milk.”)

Habit promises to study your personal biomarkers to tailor a nutrition plan just for you.

“Studying your biomarkers” means looking at a saliva sample and three blood samples taken after drinking a nutrition shake. I don’t know exactly what Habit does, but in principle, it could be very much like what some doctors do. It is a matter of what level of quality they are actually delivering, which I don’t know.

Need a few hours of supposedly superhuman mental acuity and calorie burning? Pound a ketone cocktail and keep it moving.

This is an attempt to mimic what happens during an extended fast. It may have some fraction of the benefits of actually fasting, but I doubt it has all of the benefits.

Can you control your body’s need for fuel through “intermittent fasting”? There’s an app for that.

This one I have to laugh at. Fasting doesn’t need any particular pattern. The environment of evolutionary adaptation for humans likely had a lot of random involuntary fasting. So we are likely to be designed for patternless fasting. The main thing is to (a) do enough total fasting and (b) fast for some reasonably long chunks of time, and (c) work up slowly to anything more than 24 hours so that you know your tolerance for fasting. That’s it. No particular pattern needed. Do a water-only fast (or allow unsweetened coffee and tea) when it is most convenient, which might be either when you are especially busy or when you have many distractions to keep your mind off of food (which could happen at the same time).

Let me do one more from Amanda’s first paragraph:

Late last year, the health-care start-up Viome raised $15 million in venture-capital funding for at-home fecal test kits. You send in a very small package of your own poop, and the company tells you what’s happening in your gut so that you can recalibrate your diet to, among other things, lose weight and keep it off. In the company’s words, subscribers get the opportunity to explore and improve their own microbiome: Viome “uses state-of-the-art proprietary technology” to create “unique molecular profiles” for those who purchase and submit a kit.

A lot of science is documenting that the gut microbiome is very important for health. And what you eat can have a big effect on your gut microbiome. So it would be good if we all knew more about our gut microbiomes. There is a cost here in money, trouble and disgust, but I think those willing to pay that cost will gain some benefit. (I am not yet ready to go for it, personally.)

Amanda uses the word “biohacking” several times. I consider the approach I take in my diet and health posts to be a “biohacking” approach. (Note: biohacking good; p-hacking bad.) I hope you find the biohacking approach in this blog helpful. One thing you should be reassured by is that I am currently making no effort to monetize any of what I am saying about diet and health. And what fantasies I have about monetization are about books and advice-giving rather than about selling products. (When I think about inventing new products, it is so I can eat them! I would love to see a commercial ice cream invented and marketed that was designed to have as low an insulin index as possible for a reasonable level of deliciousness. Halo Top is not terrible, but it is too focused on getting the calorie count down. With healthy dietary fats bringing the insulin index down, the healthiest ice cream would be a very rich, high-fat ice cream.)

Don’t miss my other posts on diet and health:

I. The Basics

Jason Fung's Single Best Weight Loss Tip: Don't Eat All the Time

What Steven Gundry's Book 'The Plant Paradox' Adds to the Principles of a Low-Insulin-Index Diet

II. Sugar as a Slow Poison

Best Health Guide: 10 Surprising Changes When You Quit Sugar

Heidi Turner, Michael Schwartz and Kristen Domonell on How Bad Sugar Is

Michael Lowe and Heidi Mitchell: Is Getting ‘Hangry’ Actually a Thing?

III. Anti-Cancer Eating

How Fasting Can Starve Cancer Cells, While Leaving Normal Cells Unharmed

Meat Is Amazingly Nutritious—But Is It Amazingly Nutritious for Cancer Cells, Too?

IV. Eating Tips

Using the Glycemic Index as a Supplement to the Insulin Index

Putting the Perspective from Jason Fung's "The Obesity Code" into Practice

Which Nonsugar Sweeteners are OK? An Insulin-Index Perspective

V. Calories In/Calories Out

VI. Wonkish

Framingham State Food Study: Lowcarb Diets Make Us Burn More Calories

Anthony Komaroff: The Microbiome and Risk for Obesity and Diabetes

Don't Tar Fasting by those of Normal or High Weight with the Brush of Anorexia

Carola Binder: The Obesity Code and Economists as General Practitioners

After Gastric Bypass Surgery, Insulin Goes Down Before Weight Loss has Time to Happen

Analogies Between Economic Models and the Biology of Obesity

VIII. Debates about Particular Foods and about Exercise

Jason Fung: Dietary Fat is Innocent of the Charges Leveled Against It

Faye Flam: The Taboo on Dietary Fat is Grounded More in Puritanism than Science

Confirmation Bias in the Interpretation of New Evidence on Salt

Julia Belluz and Javier Zarracina: Why You'll Be Disappointed If You Are Exercising to Lose Weight, Explained with 60+ Studies (my retitling of the article this links to)

IX. Gary Taubes

X. Twitter Discussions

Putting the Perspective from Jason Fung's "The Obesity Code" into Practice

'Forget Calorie Counting. It's the Insulin Index, Stupid' in a Few Tweets

Debating 'Forget Calorie Counting; It's the Insulin Index, Stupid'

Analogies Between Economic Models and the Biology of Obesity

XI. On My Interest in Diet and Health

See the last section of "Five Books That Have Changed My Life" and the podcast "Miles Kimball Explains to Tracy Alloway and Joe Weisenthal Why Losing Weight Is Like Defeating Inflation." If you want to know how I got interested in diet and health and fighting obesity and a little more about my own experience with weight gain and weight loss, see “Diana Kimball: Listening Creates Possibilities” and my post "A Barycentric Autobiography.

Nolan Gray: What Should YIMBYs Learn From 2018? →

A YIMBY is someone who is for allowing the construction of dwellings for people to live in even when it might have a negative pecuniary effect or cause some inconvenience for those already living nearby. “YIMBY” stands for “Yes in my backyard” and is the opposite of a “NIMBY,” which stands for “Not in my back yard.”