Lee Jong-Wha: Formal Education Fails to Produce Graduates with Skills and Technical Competencies Relevant to the Labor Market →

I have two posts I have that are highly relevant to the article flagged above:

The Hidden Cost of Not Having a Carbon Tax

One of the costs of not having a carbon tax is all the energy, air time, moralizing and moral posturing that goes on as a very ineffective alternative to a carbon tax. By taking people’s willingness and desire to be good for this purpose, we may exhaust it for other purposes. G.C. Archibald, in his book Information, Incentives and the Economics of Control, p. 5 writes:

We owe to Adam Smith the insight that matters go more smoothly if institutions are such that private and social interests coincide. D. H. Robertson (1956) put it clearly. "What do economists economize on?," he asked. This was not a rhetorical question. His answer was: Love. He explained that is scarce and that it is wasteful to depend on it for everyday arrangements that depend, or can be made to depend, simply on self-interest."

Here, he cites Dennis Holme Robertson's essay "What Do Economists Economize on?" in his book Economic Commentaries.

Experiments also suggest that if people are “good” in one way, they may feel entitled to be bad in some other way. Here is Dan Ariely’s explanation of this principle in the article flagged above:

The basic principle operating here is what psychologists call “moral licensing.” Sometimes when we do a good deed, we feel an immediate boost to our self-image. Sadly, that also makes us less concerned with the moral implications of our next actions. After all, if we are such good, moral people, don’t we deserve to act a bit selfishly?

Moral licensing operates across many areas of life. After we recycle our trash from lunch, we’re more likely to buy non-green products. After we go to the gym, we’re more likely to order a double cheeseburger. This is probably why the person who found your wallet and decided to return it felt justified in taking your cash.

If we could just have a carbon tax, then in our day-to-day activities we could just use our normal self-interest brain cells in order to behave in a way that will keep the planet from frying, and could use our generosity of spirit for other things—like, say, feeling compassion for those who desperately want to be Americans.

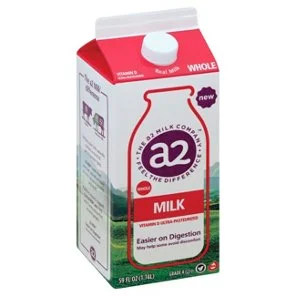

Exorcising the Devil in the Milk

In honor of Halloween tomorrow, I will give sugar a holiday from my attacks. Today, the story is about an unhealthy aspect of milk that is actually avoidable without giving up dairy.

In brief, a mutation in cows about 8000 years ago switched amino acids and created a structural weakness at a key place in the important milk protein beta casein. This weak bond then allows 7-amino-acid “peptide” or fragment called BCM7 to break off. (See the image immediately below.) If this 7-amino-acid peptide “BCM7” gets through the intestinal wall it then wreaks havoc on health. And many, many people have “leaky guts” that allow these fragments to get through the intestinal wall.

Fortunately, there is still a substantial percentage of cows that have the original gene and produce milk without this problem. If cows are tested for which variant of the gene they have, then it is straightforward to get milk with the safe “A2” beta casein protein instead of milk with the unhealthy “A1” beta casein protein. And if bulls used for commercial breeding are tested for which of these genes they have, it is straightforward to switch over a herd from a mix of A1 and A2 cattle to a herd that produces only the safe A2 milk.

A2 milk may still have some of the health issues that have been identified for milk, but since most commercial milk in high latitudes is from herds with a lot of A1 genes, most of the evidence for problems from milk is from experiments using A1 milk. So the bottom line here is this answer to my question in another post, “Is Milk OK?”: A1 milk is definitely not OK; A2 milk may well be OK other than a general caution not to consume too much animal protein. (See “Meat Is Amazingly Nutritious—But Is It Amazingly Nutritious for Cancer Cells, Too?”)

In the Boulder area, A2 milk is available not only at Whole Foods but at Safeway. Because a key test is still under patent, certifiably A2 milk that is safe is only sold by the “a2 Milk Company.” Remember to buy only whole milk: I have a post “Whole Milk Is Healthy; Skim Milk Less So,” whose title is too positive if referring to A1 milk, but is about right when referring to A2 milk.

As it stands, the a2 Milk Company is dramatically understating the likely health benefits in its marketing. It is true that double-blind tests have not been done. The rest of this post details other types of evidence out there. In this, I draw on the book at the top, The Devil in the Milk: Illness, Health and the Politics of A1 and A2 Milk, by Keith Woodford. I will only present the basic case; the book itself does a great job of rebutting counterarguments. All of the quotations and graphs below are from this book.

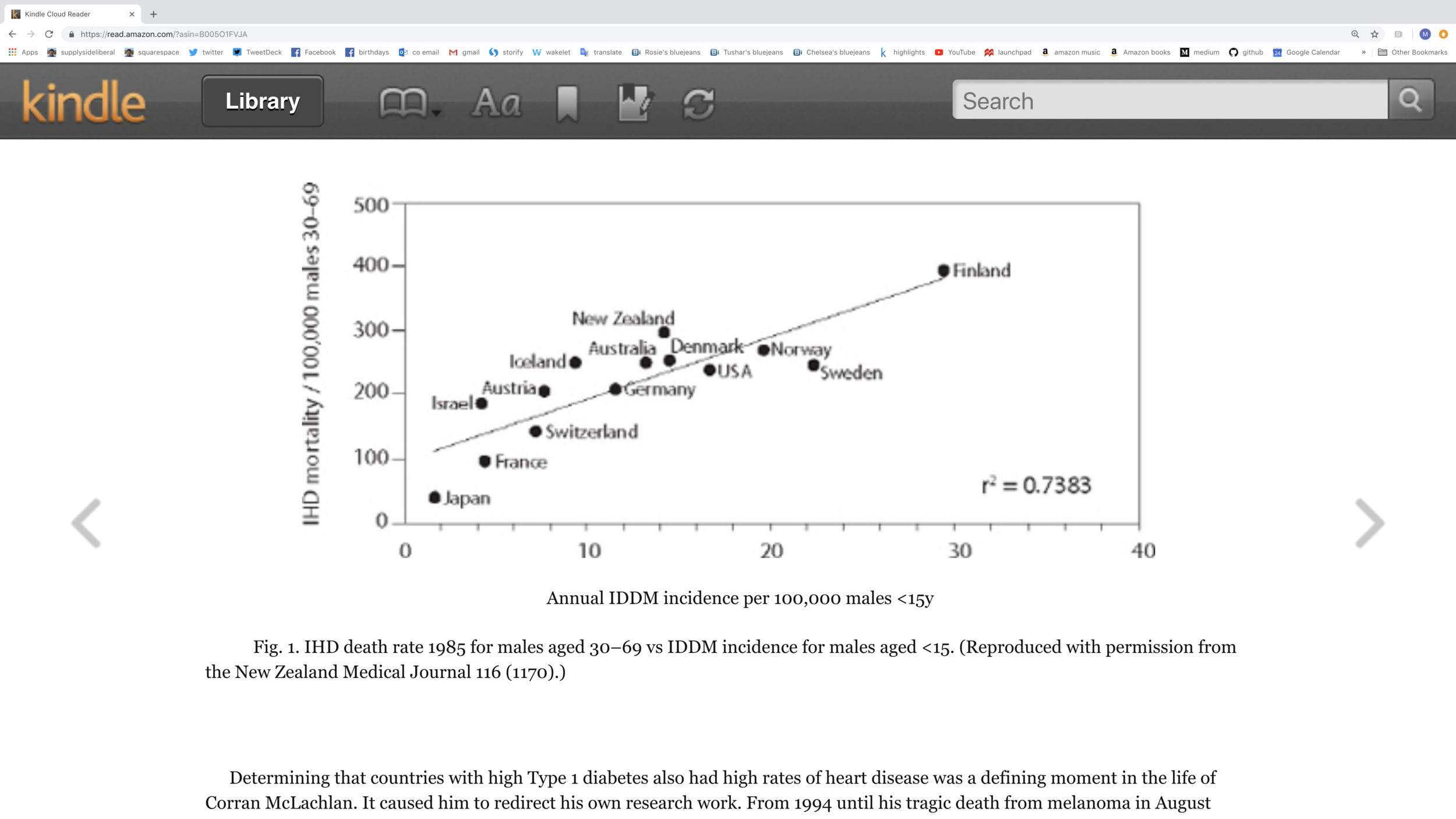

Before looking at direct evidence about A2 versus A1 milk, let me start with an intriguing fact: Type 1 diabetes (the autoimmune disease in which the body turns against and destroys its own insulin-producing cells) in children is very highly correlated across countries with heart disease in adults. (See the scatterplot in the screen shot just below.) Because heart disease is so much more common than Type 1 diabetes, this higher level of heart disease is too much to be caused by the higher levels of Type 1 diabetes. Both must have a third cause. (See “Cousin Causality.”) The set of countries is chosen as those that have good data on both diseases and are in a similar income range (so that poverty vs. riches is not a confounding factor).

Heart Disease: Below is the direct correlation between heart disease and A1 beta casein consumption across countries:

Here are some key passages about heart disease:

… the correlation between total dairy protein consumption and the incidence of male deaths from cardiovascular disease was quite weak, with an r2 of 0.26. When he looked at the relationship between the deaths and A2 beta-casein consumption it was even weaker, with an r2 of 0.16. However, the correlation between coronary heart disease and A1 beta-casein consumption was exceptionally high, at 0.71. When McLachlan excluded the A1 beta-casein from cheese consumption, the r2 value increased even further to 0.86 for male death rates in 1985 and 0.84 for the death rates in 1990. The justification for excluding cheese consumption from the analysis was based on theoretical (but not proven) evidence that the release of BCM7 is much lower from cheese than fresh milk. (Aspects of this were discussed in Chapter 2.) Female death rates followed a similar pattern, though with slightly lower r2 values.

The statistical tests show that the probability of getting chance or fluke results such as this, whereby the incidence of cardiovascular deaths can be explained to this extent by intake of A1 beta-casein, is less than one in a thousand for both males and females. …

McLachlan also compared the incidence of heart disease in the various states of West Germany. He found that 66% of the variation in deaths from heart disease could be explained by differences in the level of A1 beta-casein intake, based on the different breeds of cattle found in each state. Because there are only eight states, the correlation required for statistical significance was higher than for the other analyses. However, these results are significant at the 2% level (p< 0.02). This means that the likelihood of getting such a result by chance is less than one in fifty. …

Iceland and Finland provide some more interesting evidence. Ethnically, these Scandinavian peoples are very similar and they have similar diets. However, Finland has one of the highest levels of heart disease in the world, whereas in Iceland the incidence is only about 60% that of Finland. Is it coincidence that the intake of A1 beta-casein in Iceland is also only 60% that of Finland? (This difference in A1 beta-casein intake is because the Norske cows in Iceland have a higher level of A2 beta-casein and a lower level of A1 beta-casein in their milk than the Finnish cows.)

There are two other bits of evidence about heart disease. First, in rabbits prepared to be especially vulnerable to damaged arteries, A1 milk did much more artery damage than A2 milk. Second, it used to be a common recommendation that ulcer sufferers drink milk to reduce their symptoms. Doctors went away from this advice because it was found that drinking milk led to much higher rates of heart disease in ulcer sufferers. Note that ulcers are one type of “leaky gut.”

Type 1 Diabetes (the autoimmune disease): Below are scatterplots for Type 1 diabetes against A1 beta casein intake across countries on the left and for all beta casein intake on the right. Note how the relationship is tighter for A1 beta casein than for all beta casein. The r2 is 84% for A1 beta casein, only 46% for all beta casein (of which A1 beta casein is a part).

In addition to this cross-country evidence, there was a big, messed-up study of mice and rats in which the few non-messed-up comparisons possible show A1 beta casein causing Type 1 diabetes in two strains of rodents and no effect in one other strain.

Here is a key summary passage about Type 1 Diabetes that includes some additional bits of evidence:

All of the known jigsaw puzzle pieces linking A1 beta-casein and BCM7 to Type 1 diabetes have now been presented. Readers now need to make up their own minds as to whether the overall story is convincing. A brief summary of what we know and don’t know may help. We know for sure that there is a much higher rate of Type 1 diabetes in countries where there is a high intake of A1 beta-casein.

We know that statistically this is extremely unlikely to be due to a chance event. We also know that if A1 beta-casein is not indeed causative, no-one has been able to produce statistically significant evidence of the actual cause. What we cannot say is that we have 100% proof: we can only talk in terms of very high probabilities.

Animal trials seem to broadly confirm that A1 beta-casein can lead to diabetes. Bob Elliott found that casein diets were diabetogenic in BB rats back in the early 1980s, without knowing which particular component was the cause. Elliott and colleagues then found a very strong relationship between A1 beta-casein and diabetes in their colony of NOD mice. They also found that administration of naloxone, which counteracts the narcotic properties of opioids, stopped diabetes from developing in mice fed A1 beta-casein. Then the FAD trial showed that diabetes-prone BB rats in Canada had a higher rate of diabetes when fed A1 beta-casein in combination with Prosobee than when fed A2 beta-casein in combination with Prosobee, and that this difference was statistically significant. The rest of the FAD trial was a total mess.

Human blood tests indicate that Type 1 diabetics have more antibodies to A1 beta-casein than do non-diabetics, and these results are statistically significant. We also know that the only difference between A1 and A2 beta-casein is one amino acid in a string of 209, but that this single difference is what causes BCM7 to be formed during the digestion of A1 beta-casein. We also know that the BCM7 molecule formed from A1 beta-casein has a structure very similar to an amino acid sequence in the insulin-producing cells, and this provides a possible explanation of how antibodies attacking the BCM7 could also get confused and attack the insulin-producing cells. And we know that cattle infused with BCM7 have a reduced insulin response.

Autism and Schizophrenia: Here is a summary passage on autism and schizophrenia in relation to A1 and A2 milk:

It is now time to summarise the big picture in relation to autism and schizophrenia. It is apparent that many autistics and schizophrenics excrete abnormally high levels of BCM7 and other similar peptides in their urine. This declines markedly when these people are placed on a gluten-free and casein-free diet. The investigations by teams led by Cade, Reichelt and Shattock in three different countries confirm this.

We also know that BCM7 is released by the digestion of A1 beta-casein, but is either not released at all, or only in tiny amounts, from A2 beta-casein.

Numerous investigations show that eliminating casein and gluten from the diet leads to a marked improvement in the symptoms of autism. Once again Cade, Reichelt and Shattock stand to the fore, together with Reichelt’s colleague Ann-Mari Knivsberg. However, none of these medium- to long-term trials has been undertaken using double-blind protocols. Such trials are exceptionally difficult to conduct, but several are being planned. There is one published trial with significant results where the investigators were blind, and several other trials where they were not.

We also know that when BCM7 is injected into rats it causes them to act in a bizarre fashion, with many symptoms that resemble autism. Also, that the BCM7 enters many areas of the brain that are linked to autism, whereas similar peptides from gluten cannot access most of these areas.

We know that many thousands of parents of autistic children use a GFCF diet and believe it has benefits, but we also know that individual case studies such as this are not necessarily reliable.

We also have unsolicited testimonials supplied to A2 Corporation by parents of autistic children who have been given A2 milk. These parents believe their children are better on A2 milk than ordinary milk.12 Once again, these are only observational case histories that lack controls. However, these results seem plausible, in that we know there is unlikely to be a release of BCM7 from A2 milk.

Other Autoimmune Diseases and Allergies: For other autoimmune diseases, much of the evidence is about milk or beta casein in general. But BCM7 has the right kind of biological activity to be a prime suspect. For allergies and milk intolerance, anecdotal evidence is decent that A2 milk is less problematic. (Indeed, some people who think they are lactose intolerant might find they do OK with A2 milk.)

Once again, readers can now use the evidence to draw their own conclusions. In the case of milk intolerance and allergy, it seems likely that A1 beta-casein, and the milk devil BCM7 that is derived from it, are indeed implicated. Is it likely that so many consumers could all be wrong, particularly when the symptoms, such as diarrhoea, are well defined? Also, the story is totally consistent with what we know of the pharmacology and biochemistry of BCM7.

In the case of the auto-immune diseases discussed in this chapter, the story is somewhat more murky and speculative. What we do know for sure is that for each disease there is one or more environmental trigger. We also know that milk keeps coming up as a prime candidate. If milk contains the cause then it almost certainly has to be one or more bio-active proteins in the milk. It is also likely that opioids are involved. It is hard to go past BCM7 as a likely candidate.

Conclusion: As I mentioned above, this is only the basic case against A1 milk. Keith Woodford’s rebuttals of counterarguments are also very important. If you doubt the basic case, get the book on Kindle and check out the rest of the argument. To the simple counterargument “Why haven’t I heard this already?” there is a story of commercial and scientific politics, plus the simple fact that people can cook up arguments to disregard anything but expensive double-blind trials, and then argue that those arguments mean it isn’t worth doing those expensive double-blind trials.

Some New Zealand dairy farmers have been changing their herds over to A2 cows, but it is still a small fraction of all diary farmers there. If only a dairy powerhouse of New Zealand shifted to A2 herds more fully, it would change the commercial and scientific politics there, which in turn would help us get additional evidence about A1 vs. A2 milk.

In finding A2 dairy products, one basic fact to know is that the mutation at issue is mainly only in cows. Any goat dairy product is A2 and so safe in this sense. Buffalo dairy products (like the Buffalo mozzarella at Costco) is also A2. And the A1 gene is rare in sheep, which combined with the fact that BCM7 is probably not released as easily from cheese makes me feel safe with Manchego cheese from Costco, which is from sheep milk. Butter doesn’t have a lot of protein in it anyway, but I have been eating mostly goat milk butter from Whole Foods. Ghee, or clarified butter, is safe because it has no protein in it.

At retail, the thing I can’t yet find is A2 cream or A2 half-and-half. I have resorted to combining A2 milk with organic cream from Costco—which has some A1 protein in it, but hopefully not too much, since it is heavily fat.

Let me end by saying that the one thing I would be very scared to do would be to feed infants or young children regular A1 milk or the many dairy products (including many types of infant formula) that have A1 beta casein in them. Infants’ guts tend to be especially permeable to peptides like BCM7. Human milk is safe.

Someone asked me whether nursing mothers should avoid drinking A1 milk themselves. The answer to that is easy: nursing mothers should avoid A1 milk for the sake of their own health just like all other adults and children.

I. The Basics

II. Sugar as a Slow Poison

Best Health Guide: 10 Surprising Changes When You Quit Sugar

Heidi Turner, Michael Schwartz and Kristen Domonell on How Bad Sugar Is

Michael Lowe and Heidi Mitchell: Is Getting ‘Hangry’ Actually a Thing?

III. Anti-Cancer Eating

How Fasting Can Starve Cancer Cells, While Leaving Normal Cells Unharmed

Meat Is Amazingly Nutritious—But Is It Amazingly Nutritious for Cancer Cells, Too?

IV. Eating Tips

Using the Glycemic Index as a Supplement to the Insulin Index

Putting the Perspective from Jason Fung's "The Obesity Code" into Practice

Which Nonsugar Sweeteners are OK? An Insulin-Index Perspective

V. Calories In/Calories Out

VI. Wonkish

Anthony Komaroff: The Microbiome and Risk for Obesity and Diabetes

Carola Binder: The Obesity Code and Economists as General Practitioners

Analogies Between Economic Models and the Biology of Obesity

VIII. Debates about Particular Foods and about Exercise

Jason Fung: Dietary Fat is Innocent of the Charges Leveled Against It

Faye Flam: The Taboo on Dietary Fat is Grounded More in Puritanism than Science

Confirmation Bias in the Interpretation of New Evidence on Salt

Julia Belluz and Javier Zarracina: Why You'll Be Disappointed If You Are Exercising to Lose Weight, Explained with 60+ Studies (my retitling of the article this links to)

IX. Gary Taubes

X. Twitter Discussions

Putting the Perspective from Jason Fung's "The Obesity Code" into Practice

'Forget Calorie Counting. It's the Insulin Index, Stupid' in a Few Tweets

Debating 'Forget Calorie Counting; It's the Insulin Index, Stupid'

Analogies Between Economic Models and the Biology of Obesity

XI. On My Interest in Diet and Health

See the last section of "Five Books That Have Changed My Life" and the podcast "Miles Kimball Explains to Tracy Alloway and Joe Weisenthal Why Losing Weight Is Like Defeating Inflation." If you want to know how I got interested in diet and health and fighting obesity and a little more about my own experience with weight gain and weight loss, see “Diana Kimball: Listening Creates Possibilities” and my post "A Barycentric Autobiography.

Christian Kimball: Revelation and Satan

Chris Kimball in 2008

When my brother Chris read my post “Less is More in Mormon Church Meetings,” he wrote some excellent comments on that post immediately, but also had more to say. Below is his guest post, followed by links to Chris’s other guest posts on supplysideliberal.com.

What Happened?

In the September 2018 General Conference of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (the “Church”), the President of the Church, Russell M. Nelson, and the next in line and current 1st Counselor, Dallin H. Oaks, spoke of revelation and referred to Satan in talking about the proper name of the Church and about the Proclamation on the family (“The Family: A Proclamation to the World”).

This is a big deal.

It’s not as though the words are never used. In my lifetime there have been about 4,700 talks or sermons at Church general conferences; the word “revelation” has come up almost 3,900 times, and the word “Satan” has come up more than 1,800 times.

It’s not that I take the words literally. If you view “revelation” as a Moses-on-Sinai theophany, and “Satan” as ultimate evil personified, then every use is a big deal by definition. That’s not me, but it is descriptive of mainstream orthodox Church members. Most importantly, Presidents Nelson and Oaks know that about mainstream orthodox members, and know they are calling on those literalist beliefs when they use the words.

My Take

Without pretending to read minds, what I hear in the references to revelation and Satan is an argument by authority and fear, suggesting that these men see existential threats about which reason and persuasion have failed and all that’s left is authority and fear. Couched in the language of the Church, these are calls to arms against an enemy.

The Name: President Nelson says the name of the church is The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. This scans as trivially true. But he then says to use nicknames is “a major victory for Satan.” Fighting words.

Escalating to such an extent says to me that the word “Mormon” has become dangerous, has become a near existential threat that must be addressed. To make sense of “threat” I reflect on phrases I have heard and used in the 21st century: “big tent Mormonism,” “More Than One Way to Mormon” (which I associate with the Sunstone Educational Foundation around 2016), and “middle-way Mormons” (More millennial Mormons are choosing a middle way — neither all-in nor all-out of the faith, Salt Lake Tribune, September 29, 2018, an article in which I was quoted). Considering these phrases, it feels like President Nelson is saying NO--rejecting the phrases, rejecting the words, rejecting the idea. His emphasis on the proper name, and most importantly his rejection of nicknames, stands as a powerful reinforcement of boundaries. It suggests “Mormon” as it has come to be used threatens the integrity of the Church. That “Mormon” allows too much inside the tent. The Church has lost control of the word (not legally, but sociologically) but cannot afford to lose control of who claims it.

The sense of boundary, of defining ins and outs all over again, is reinforced by post-conference reports of members being challenged with claims of heterodoxy or apostasy for slipping in a “Mormon” in the wrong place. On a personal level, I recognize an outing. I am “ethnically” Mormon to the nth degree. But I feel excluded from the body of the Church by having the name reinforced. I respect the Church’s requests (although the lack of an adjective form is causing conniptions for everyone I know). But I don’t sustain the move, I don’t think it is necessary or wise, I don’t believe. Yet by his rhetorical choices, President Nelson has made the name an article of faith, which now defines me as an outsider.

Why is a noted heart surgeon with decades of experience in high church callings resorting to “revelation” and “Satan”? I hear the call to authority and fear as the last arrows in his quiver. President Nelson has tried reason and persuasion. He spoke to the name issue in the April 1990 general conference. In the following conference, in October 1990, Gordon B. Hinckley countered with a call to make good use of the nickname “Mormon” and addressed Elder Nelson’s earlier address and arguments, by name. Argument has been tried, and failed. This time around, Hinckley is gone and Nelson is in charge. With what might be heard as petulance and is certainly defensive and last-straw-ish, President Nelson says (emphasis in the original):

It is not a name change.

It is not rebranding.

It is not cosmetic.

It is not a whim.

And it is not inconsequential.

Instead, it is a correction. It is the command of the Lord.

I think the name correction is a point President Nelson sincerely feels is mandatory, a must have. And the only thing he’s got left to make the point is authority and fear.

The Proclamation: About the Proclamation (understood to be in opposition to same-sex marriage and LGBTQI issues generally), President Oaks says: “Modern revelation defines truth as a ‘knowledge of things as they are, and as they were, and as they are to come’ . . . That is a perfect definition for the plan of salvation and ‘The Family: A Proclamation to the World.’” And then punches it up with “Satan . . . seeks to destroy God’s work . . . He also seeks to confuse gender, to distort marriage, and to discourage childbearing.”

As I have written elsewhere, for a church and religion built on gender essentialism--that declares a personified embodied gendered essentially cis male God the Father, and a weakly recognized but still embodied gendered essentially cis female Mother in Heaven—there is no room for homosexuality or same-sex marriage or family structures other than binary pairs. Where gender is essential and defining, LGBTQI issues are threatening. In practical effect, the Church’s only option is exclusion.

But why is a highly respected jurist with equally many decades of high church experience resorting to “revelation” and “Satan”? I hear the call to authority and fear as the last arrows in his quiver. President Oaks knows the arguments have been made in courts across the country—and that they have failed. The Proclamation was written to assemble church teachings about family and gender and marriage so that it could be presented to courts (starting with an amicus brief in Hawaii in 1995) to argue for an overriding interest in preserving one-man-one-woman marriage. The argument failed in the courts, partly because society has moved, and partly because science and (secular) history are on the other side. The result is that from and after Obergefell in 2015 the Church and especially President Oaks has moved to “revelation” and “Satan” rhetoric.

I think the opposition to same-sex marriage is a point President Oaks sincerely feels is mandatory, a must have. And the only thing he’s got left to make the point is authority and fear.

What’s Next?

Doing my own prophesying here, I think this is dangerous territory for the Church, as it would be for any church. As I read Western culture in the 21st century, including at least two generations younger than me, I think “in or out—follow me or bust” rhetoric is more likely than not to end at out and bust. There is a risk (and I hear the whisperings) that the name comes across as trivializing revelation and criticizing past authority, leading to a far-reaching re-assessment of the value and power of authority. There is a risk (and I hear the whisperings) that the LGBTQI issues are not believed. That there are now and will be a growing number of members viewing the Church’s stance as opinion demanding but not deserving loyalty. Certainly I hear these whisperings among people who are inclined to disagree anyway. But from surprising corners I hear comments like “I agree with the principle but not the method.”

What does it mean when you shoot your last arrow and it doesn’t strike the target?

Don’t miss these other guest posts by Chris:

Christian Kimball: Anger [1], Marriage [2], and the Mormon Church [3]

Christian Kimball on the Fallibility of Mormon Leaders and on Gay Marriage

In addition, Chris is my coauthor for

Population Map of the World, 2018 →

Thanks to Tadas Viskanta and Max Roser for flagging this.

A Conversation with Clint Folsom, Mayor of Superior, Colorado

In the US political system, one of the most important dimensions of social justice is a matter of local politics: giving people of modest means a chance to live in nice towns and cities within a reasonable commute from jobs. I felt a tug of civic duty to do my part toward this end in my home town of Superior, Colorado. (See “Miles Moves to the University of Colorado Boulder.”) Superior, Colorado is a town of 4 square miles, with 12,483 residents in the 2010 census. Along with Louisville across the Denver-Boulder Turnpike (US Route 36), it is the first town on the road from Boulder to Denver after the greenbelt that surrounds Boulder.

In Colorado, we vote by mail; my ballot is already sitting on my kitchen table. But even in a town of Superior’s size, I thought I could make a bigger difference as a journalist with an activist tilt than as a voter alone. My interview here of Clint Folsom, Mayor of Superior, who is up for reelection this month, is my first effort in this direction.

When I emailed him to ask for an interview at his mayoral email address, Clint replied with a personal email account, explaining that since my interview seemed campaign related, he thought he should avoid using his mayoral email account. We met at his real estate brokerage office in the neighboring town of Louisville because like most small town mayors, Clint isn’t provided any office space at Superior’s Town Hall.

Contrary to some negative stereotypes, I have the view that successful politicians are usually quite talented, smart and impressive people. Clint has the kind of intelligence, social skills and self-confidence that lends itself to being a successful politician.

Clint told me he had moved to Superior 20 years ago a few years after graduating from the University of Colorado at Boulder. I said how much I had enjoyed living in Superior the last 2+ years. One of the most recent things I have come to appreciate about Superior is how, without leaving Superior, I can get from Safeway, Costco and Whole Foods any of the particular types of food I have been recommending in my Tuesday diet and health posts that I can get in any store in the Boulder area. Clint said that when he talks to other mayors, the retail they have on their wish list for their cities was the kind of retail Superior has. Those stores generate a lot of sales taxes as well as benefits for consumers. (There is also an excellent mall in a neighboring town—FlatIron Crossing—that generates benefits for consumers from Superior, but no sales tax revenue for Superior.)

I had reassured Clint that this was a combined in-person, email interview, and that what we said on email could overrule anything said in person. I had emailed four question in advance; the last I added on the spot. Here they are, with a distillation of Clint’s answers.

1. What do you see as the big issues going forward for the city government of Superior?

Clint explained that Superior has a town manager, who has the primary agenda-setting power in the town, so that the mayor’s official role is chair of the “Board of Trustees,” which is just another name for the city council of Superior. In addition, as mayor he has substantial ceremonial duties. He said he does ribbon cuttings with the giant scissors for new businesses—big and small—in Superior, and talks to school children about the town government.

Clint also attends regional meetings of mayors. There, they mostly talk about transportation issues. A big issue locally is that a ballot initiative was passed that raised taxes in order to pay for passenger rail from Denver to Boulder. This hasn’t happened. The cost was seriously underestimated at the time of the ballot initiative, in part due to extra costs associated with new safety regulations, specifically PTC or positive train control, which are intended to reduce the possibility of head-on collisions. The original plan was for the transportation authority to buy time on an existing freight train track but that was complicated because the owner of the track won’t allow power lines needed for electric passenger trains to be installed above the tracks. Diesel passenger trains are probably the only option, but diesel trains take a long time to stop and start, making it hard to have as many stops and slowing things down generally. At that point, busses become the more convenient and faster option. Clint thinks everyone should face reality and redirect those funds from a rail project that no longer looks so attractive toward other transportation initiatives. (I suggested more frequent bus service as a simple possibility. For example, currently the bus to the Denver airport only runs once an hour, except at peak times.) Clint said changing directions would require another ballot initiative, coupled with an extensive public education campaign—no easy thing. In the absence of that kind of facing of reality, Clint said that local voters understandably are skeptical of other transportation ballot initiatives, even those that are at the state, rather than the regional level.

In direct answer to my question of big issues going forward for the government of Superior, Clint talked about the effort to find some community space that could be used for gatherings, say of up to 150, and subdivided for smaller classes like scout meetings or art classes. Currently, the available spaces would only accommodate about 25 people at a time. A big discussion was whether a community space of this sort should be combined with a recreation facility. The trouble there was all the competing recreation facilities in town that drive down the benefit/cost ratio for an additional recreational facility. They Board of Trustees started by talking about something modest, but the benefit wasn’t enough to get people excited. Then the Board of Trustees started talking about something that could get people more excited, but it was quite expensive. Clint now leans towards a community space somewhere in the new Downtown Superior development. He would also like to explore the idea of expanding the usage of Superior’s two outdoor pools which are currently only open for three months of the year during the summer. A retractable roof or other options to cover one of the pools could allow for year-round usage and a better use of our existing assets.

2. I love the trails in Superior, but one thing I admire on the occasions when I take a walk on the Coal Creek Trail in Louisville is the "There is No Poop Fairy" campaign. I wondered if Superior might do a similar campaign. Relatedly, I have thought that I see some extra dog poop on trails where garbage cans are far away.

Clint liked this idea, and said that an open space committee could take it up. (There are actually two different open space committees in Superior.)

3. Superior is such a wonderful city, I wanted to ask about your views on allowing construction (particularly near the bus station) to make Superior financially accessible for additional people to move in and enjoy everything we have here.

It was interesting to see Clint’s mind at work here. He sees it as important for Superior to a town where people at different income levels can live, and agreed that the area near the bus stop at the Denver-Boulder Turnpike is a great place to put additional residential developments. This land is currently part of a large shopping area. Big box retail has done well in that area, but smaller retail hasn’t always done well there, and more people living right there could help. He said any retail area has to keep running to stay in the same place; doing nothing usually leads to decline. Adding residential developments right there in the retail district near the bus stop could be just the right thing to keep that retail area vigorous. He mentioned how much that retail district contributes in sales taxes—its health matters for Superior’s finances.

A nice example of how Clint was thinking through all the practicalities of new residential development in the retail district by the bus stop was a point he made that residential parking needs and retail parking needs dovetail nicely together: peak residential parking needs are at night, while peak retail parking needs are during the day. So it could work well for retail and residential to share parking lots in that area.

Clint said that, of course, height of apartment or condo buildings in that area would be one of the most controversial issues. I made the case that if the developer agreed to make a tall building beautiful in exchange for a liberal height requirement, it could be great to have a skyline for Superior with a landmark building that would give homes to many people.

One thing I had thought about before the interview, but forgot to mention to Clint is that as soon as one thinks on a regional basis, even if a new building is made up of luxury apartments, it still contributes to affordable housing, because everyone who moves to one of the new luxury apartments frees up another housing unit somewhere in the area. As people of middle incomes then move to fill those vacancies, at the end of the chain, affordable housing opens up. That is, because of supply and demand, it is the total number of units that matters most for “affordable housing” in the region, not whether those particular units are low-rent or not.

4. I'd also be interested in asking a few "horse-race" questions. I don't yet have a good sense of local politics and where the battle lines (if any) are drawn, and how strong the different sides are.

Mayors and Board of Trustee members have four-year terms in Superior, staggered at two-year intervals.

Clint is running against two other candidates for mayor: Gladys Forshee and Jack Chang. Clint said he had won 80% of the vote against Gladys in 2014. Gladys is a long time resident of Original Town Superior which is a collection of small miners cabins—some over 100 year old when Superior was founded as a coal mining town. Gladys is a staunch defender of keeping Original Superior as-is.

About Jack Chang, Clint said that Jack had made an offer to buy some land from the Town of Superior at the intersection of Coalton and McCaslin to build a charter school and what sounded like a startup incubator. The land in question wasn’t for sale and the Board of Trustees unanimously rejected his purchase contract then a week later Jack decided to run for mayor. Clint and many others thought that was a conflict of interest on Jack’s part. I argued that if Jack was basically a one-issue candidate on behalf of that idea for using that plot of land, that in the unlikely event that we won the election, he might reasonably be said to have enough of a mandate for that to overcome the conflict-of-interest worry.

I asked about the other races. The other Board of Trustees races seem quite competitive. Six candidates are running for three seats. Unfortunately, even for Clint, it is very hard to discern the policy views of those running for the Board of Trustees. Clint said that pretty much everyone would say they were for “smart growth” and “careful growth” and for “honoring past agreements.” But these phrases hide differences that show up when specific issues come up for a vote by the Board of Trustees.

Some Trustees in the past have said in meetings (that are all on video) that they don’t think low-income people are a “good fit” for Superior. But you wouldn’t know what I would call their “anti-poor” views from their campaign signs, which have no real content other than the name. (Name recognition is the only thing the signs are going for.)

The ballots for town officials in Superior are nonpartisan. Sometimes voters want to know Clint’s party. Clint describes himself as “unaffiliated” with any political party. My reaction was that it would be much more useful to know whether a candidate was in favor of making it possible for people of all income levels to live in Superior or not than it would be to know their political party.

5. About how many hours do you spend as mayor, and how much are you paid as mayor? What about Board of Trustees members?

Clint said he spend about 20-30 hours a week as mayor. He has been paid $500 a month for being mayor; that will go up to $750 a month in 2019. He guessed that Board of Trustees members spend about 10-25 hours a week on thing related to that role. They have been paid $300 a month; that will go up to $500 a month next year. Clint said they aren’t doing it for the money. At those rates, I believe that.

Vindicating Gary Taubes: A Smackdown of Seth Yoder

This flawed early version of the article is no longer available

Update, March 9, 2019: Seth Yoder responds to this post here.

Gary Taubes’s book The Case Against Sugar was the starting point for my interest in fighting the rising tide of obesity in the world. (See “A Barycentric Autobiography.”) Gary Taubes is so important to efforts to fight obesity that in addition to many of my posts that quote Gary, many posts are more directly about Gary. For example, see:

In these posts I have defended Gary’s substantive views, but have, on several occasions, criticized Gary himself. In particular, in “The Case Against the Case Against Sugar: Seth Yoder vs. Gary Taubes” I write:

Seth Yoder, in his post "The Case Against the Case Against Sugar" fully convinced me that Gary Taubes displays a serious lack of reportorial honesty in his book The Case Against Sugar. And Seth somehow made reading through the trainwreck of how Gary Taubes routinely misquotes or otherwise misrepresents dead people's views perversely entertaining.

Seth's devastating demonstration of Gary Taubes's lack of reliability as a historian means I need to examine places where I have relied on information from Gary …

and in “Against Sugar: The Messenger and the Message” I write:

Gary Taubes has risen high enough that he is set up for a fall. And there is plenty of dirt. He has played fast and loose with some of his history, putting words in the mouth of long-dead scholars they said or meant, and pointing out that people he disagrees with were compromised by sugar-industry ties, but neglecting to point out that people he agrees with were compromised by other food-industry ties.

This post gives Gary Taubes’s side of the story, which I find fully persuasive. I retract the criticisms I have quoted above—and others I have made that are derivative from these two. I consider Gary Taubes vindicated, and will put notes in my earlier blog posts that criticize Gary linking to this post.

I few days after I posted “Against Sugar: The Messenger and the Message,” sparked by the Wired article above[GT1] , I received an email from Gary Taubes about the serious inaccuracies in that article. Wired ultimately revised the article significantly to address errors. [GT2] As you can see above, they felt they had to change the title.

Since I was young, I have looked up to the authors of most of the books I read. So I was delighted to be in correspondence with Gary. I am also grateful that he has given me permission to share some of our correspondence, as it broadened beyond the Wired article. I have lightly edited for focus and continuity and minor corrections, and omit salutations.

Gary: I just read your latest blog post on the Wired article about me and NuSI as it was shared with me on twitter.

Regrettably that article got, well, virtually everything wrong …

… we’re all on the same side here, I assume, trying to improve the health of the public and perhaps the relevant scientific communities …

Miles: I would be glad to publish anything you want to say in ongoing debates as a guest post. My readers are quite sophisticated. I would also be very interested in your reaction to any of what I have written on diet and health. Each Tuesday's diet and health post has links to all my other posts on diet and health.

Gary: I wouldn’t have bothered doing this if I didn’t appreciate what you’re doing and think your readers are indeed sophisticated and thoughtful. Although I don’t think I’ll have time to go back and read (or read in some cases) your previous posts. I should be working on my next book. At the moment this is all more or less procrastinating.

By the way, I was just searching your website and I noticed that Seth Yoder seems to have influenced your thinking on the quality of my reporting. I never read his review of TCAS because I had many discussions with him when he was doing his take down of GCBC. I estimate there are indeed maybe 200 errors in GCBC from misplaced ellipses in quotes to a few whoppers that still mystify me. That said, I found Seth's fact-checking to be third-rate at best. I could share that e-mail exchange with you, if you'd like. It ends with him asking me if we might want to hire him at NuSI and me suggesting that my former colleague Peter Attia has very little tolerance for sloppiness (mine included) and so I very much doubt he would get a job. I never respond to these people publicly (the same goes for Guyenet and Freedhoff and Kokor) because life is short and there are more important things to do. I think the problem with blogging is that it doesn't have the requirement that journalism does that the writer/reporter go to the source to ask for comments. So had someone like you asked me about Yoder, I'd say, "give me some of his key points and I'll see what I can do" and then I'd see what I could do or tell you I'm too busy. As is, this slowly permeates through the blogosphere. I still don't think it's worth responding publicly to these folks (Yoder, after all, is just a young man with a grudge and too much time on his hands) but I do wish folks like you would reach out, just like a reporter would have to, and assure you're getting the story right. I realize this isn't what bloggers do. I'm just wishing here that it was.

Anyway, if you have any questions in the future, feel free to ask. And if you'd like to give me a few of Yoder's main points about TCAS, I'll try to find the time to respond.

Miles: Thanks! I'd love to do a blog post giving your response to Seth Yoder if you have material from your interaction with Seth Yoder that you could put on the record. I found that when I spoke highly of your work, people kept directing me to Guyenet and Yoder so I felt I had to take that seriously. I think Seth's accusations are much more serious than anything Guyenet says. So I would love to know how to answer what Seth says better. I can work with quite raw raw-material on that front.

I am delighted to be in correspondence with you. I confess that I assumed too quickly that I was too much of a small fry for you to respond.

Gary: As I said my earlier experience with Yoder was so discouraging that I lost interest in anything he wrote. … It wasn't just that his goal (as he admitted to me) was to dismiss the message of my books by nit-picking them as close to death as he could get them, but that he did a lousy job of nit-picking. …

Miles: I didn't think Seth was convincing when it came to any substantive scientific question. The one place I did take him seriously was in his claim that your characterization of the views of dead people often didn't adequately reflect the conventionality of their views. Few were sounding the strong anti-sugar note that your quotations sometimes make it sound as if they did. You made them seem more simply anti-sugar than they really were, when their views were quite complex and often quite muddy. This is consistent with what you said in the email you just sent: your books are needed precisely because a strong and clear anti-sugar message was not there before. But, other than Yudkin himself, I don't see that there was a golden age in the past when the anti-sugar message was sounded in a clear and strong way by researchers.

I'd love to get your responses to these bits of Seth's blog post that worried me. What follow are seven quotations from Seth’s blog post, which in turn often have quotations from your book.

[Editing note: Between the two divider lines, the unindented words are Seth’s. The indented words are Seth quoting others. Gary’s response picks up immediately after the second divider line.]

1. [Seth quoting a source:]

Influential British and Indian physicians working in the Indian subcontinent had discussed the high and apparently growing prevalence of diabetes among the “lazy and indolent rich” in their populations, and particularly among “Bengali gentlemen” whose “daily sustenance . . . is chiefly rice, flour, pulses, sugars.”

“There is not the slightest shadow of a doubt that with the progress of civilization, of high education, and increased wealth and prosperity of the people under the British rule, the number of diabetic cases has enormously increased,” observed Rai Koilas Chunder Bose, a fellow at Calcutta University, noting that perhaps one in ten of the “well-to-do class of Bengali gentleman” had the disease.

Compare this to pages 102-103 of GCBC:

To British investigators, it was the disparate rates of diabetes among the different sects, castes, and races of India that particularly implicated sugar and starches in the disease. In 1907, when the British Medical Association held a symposium on diabetes in the tropics at its annual conference, Sir Havelock Charles, surgeon general and president of the Medical Board of India, described diabetes among “the lazy and indolent rich” of India as a “scourge.” “There is not the slightest shadow of a doubt,” said Charles’s colleague Rai Koilas Chunder Bose of the University of Calcutta, “that with the progress of civilization, of high education, and increased wealth and prosperity of the people under the British rule, the number of diabetic cases has enormously increased.” The British and Indian physicians working in India agreed that the Hindus, who were vegetarians, suffered more than the Christians or the Muslims, who weren’t. And it was the Bengali, who had taken on the most trappings of the European lifestyle, and whose daily sustenance, noted Charles, was “chiefly rice, flour, pulses and sugars,” who suffered the most—10 percent of “Bengali gentlemen” were reportedly diabetic.

The recycling of his own work notwithstanding, it’s a bit of a selective interpretation of the source material.(5) The following are some choice quotes that Taubes does not mention:

[The Hindus] generally eat more than is actually necessary for the maintenance of health, are more susceptible to diabetes than their Mohammedan or Christian brethren. It is difficult to state the part food plays in the production of diabetes, and what part gluttony supplies in the manufacture of sugar within the system. True it is that our diet chiefly consists of rice, flour, pulse, and cereals of diverse kinds; but so long as there does not exist the essential cause of diabetes, which Is still unknown, they exert little or no deleterious effects upon our health, and a man may continue to take carbohydrates and sugar lifelong, and still may not suffer from diabetes; he might suffer from temporary glycosuria. I do not agree with those who believe that carbohydrates are the only factors of diabetes, for meat-eaters are not immune against the disease.

[…]

The following articles of diet are recommended [for diabetics]: New rice, curd, flesh of animals living in swamps, fish, sweets, wines, vinegar, excess of oil, and onions. […] The following articles of diet are especially recommended, for they are considered to be very beneficial: Barley, flour of old wheat, Moong dal, Arabar dal, Chena dal (Bengal grain), fried rice, sesamum seeds, meat juice, old wines, old honey, whey, sparrows, pigeons, rabbits, snipe, peacock, venison.

[…]

And, although the carbohydrate excess in the food of the Indian is very great, still, just as in Europe, where the consumption of sugar, vegetables, and beer may be also in excess, the essential cause of diabetes must be present, or otherwise the factors mentioned will not determine the disease. So it is in the East.

[…]

Exercise, as a rule, is disliked by the gentlemen class of Bengal after a certain age, and members of this service form no exception. Further, in addition to sedentary habit, excessive mental labour, often in over crowded court-rooms, and ingestion of heavy, fatty, starchy, and saccharine meals, seem to be no unimportant factors in the causation of the disease among this class of highly useful Indian public officers.

If we take the whole of the text into account, we find that these Bengali gentlemen not only consume starches and pulses, but also heavy fatty foods, and they consume it all in excess. Additionally, they don’t like to exercise according to these physicians. Might these lifestyle factors play a role in diabetes? Moreover, the physicians themselves make it clear that they do not think sugar and carbs cause diabetes since diabetes can also be present in those that do not eat carbs and be absent in those that consume a lot of carbs. If these physicians thought carbs promoted the development of diabetes they would not be prescribing diets that included honey, flour, rice, sweets, and wine in the treatment diets. Why doesn’t Taubes mention this?

2.

Continuing… Taubes claims that this point about Indian diabetics was “singularly compelling” to an influential diabetes specialist named Frederick Allen.

Allen found this point singularly compelling. These early Hindu physicians, after all, were linking diabetes to carbohydrate consumption and sugar more than a millennium before the invention of organic chemistry and its revelations that sugar, rice, and flour were carbohydrates and that carbohydrate “in digestion is converted into the sugar which appears in the urine.” “This definite incrimination of the principal carbohydrate foods,” Allen wrote, “is, therefore, free from preconceived chemical ideas, and is based, if not on pure accident, on pure clinical observation.”

First, there is no evidence that Allen found this “singularly compelling.” Secondly, unlike Taubes, Allen discusses evidence both for and against the theory that carbohydrate consumption is associated with diabetes.(6) Let’s look at the full quote (emphasis mine):

This definite incrimination of the principal carbohydrate foods is, therefore, free from preconceived chemical ideas, and is based, if not on pure accident, on pure clinical observation. But Bose himself, with a more modern viewpoint, states that he does not know how much the heavy carbohydrate diet and the gluttony of the Hindus may have to do with the great prevalence of the disease among them; but unless the unknown cause of diabetes is present, a person may eat gluttonously of carbohydrate all his life and never have diabetes.

Having the full quote changes Allen’s tone, wouldn’t you say? Let’s look at what else Allen wrote immediately following the out-of-context quote:

Among the authorities on diabetes, von Noorden declares against any relation between the eating of carbohydrate and the incidence of the disease. […] A. L. Benedict considers that though some diabetics give a history of excessive eating of sugar or carbohydrates, many non-diabetics are guilty of equal excesses, particularly young girls who live on candy. Supporters of the sugar-theory call attention to the concomitant increase of diabetes and of sugar- consumption. But if sugar were a cause, diabetes should be more prevalent among the young, especially girls; and a larger proportion of case-histories should show sugar-excess. The products of carbohydrate digestion and metabolism are not toxic, and indigestion generally stops the excess before long.

3.

Relating back to the Prologue of this book, on page 100 Taubes describes the intrepid research of Emerson and Larimore:

By the mid-1920s, the rising mortality rates from diabetes in the United States had become the fodder of newspapers and magazines; Joslin, the Metropolitan Life Insurance Company, and the New York State commissioner of health were all reporting publicly what Joslin was now calling an epidemic. When Haven Emerson, head of the department of public health at Columbia University, and his colleague Louise Larimore discussed this evidence at length at two conferences in 1924—the American Association of Physicians and the American Medical Association annual meetings—they considered the increase in sugar consumption that paralleled the increasing prevalence of diabetes to be the prime suspect.

But is this actually true? Was sugar the “prime suspect”? From the Emerson and Larimore article:

The food shortage expressed itself not so much in the lack of sugar and carbohydrates as in lack of fats, which should make one suspect that it is not the quality but the gross quantity of food (calories) that plays the chief part in development of a high diabetes death rate in a community where more food is eaten than is required. (1)

So, the sugar shortage, in effect, was the shortage of all foods. Sugar consumption was used only as a proxy. This is repeated in the text:

One index of the tendency of our people to use larger amounts of food is the record of per capita consumption of sugar, which is offered here not as an explanation of the increased death rates from diabetes in recent years, but more as a sign of the tendency to excesses in the use of foods of all kinds, beyond the needs of persons for foods in proportion to their expenditure of energy at the different ages of life, and in particular in the later decades.

If any prime suspect is fingered by the authors, it is the difference in physical activity between those that have diabetes and those that do not. This point is brought up many times in the text and is the closing sentence from Emerson.

4.

In a series of articles written from the late 1920s onward, Bauer took up Bergmann’s thinking and argued that obesity was clearly the end result of a dysregulation of the biological factors that normally work to keep fat accumulation under check.

However, if one actually reads the series of articles, one might conclude that they are not exactly the ringing endorsement that Taubes claims:

The question of obesity has occupied the minds and pens of so many workers that it seems scarcely necessary to add another publication. Endocrinologists, especially, have taken a great interest in the subject, and as a result we find the literature filled with references to the relation between endocrine disorders and obesity. While we grant that endocrine dysfunction may be a cause of obesity we feel that these cases form a small, numerically almost insignificant part of the obese patients that present themselves in the clinic. It shall be the purpose of this report to review briefly the present concepts of the nature of obesity and to present a case that illustrates the dangers of an “endocrine diagnosis” in cases which, on careful study, reveal another, more likely, basis for the obesity. (17)

(bolding mine, italics in the original)

And what does Dr. Bauer recommend in treating obesity? Why low calorie diets and more exercise, of course!

In no case should obesity be treated without the prescription, first of all, of a dietetic regimen. All other therapeutic procedures are secondary to this one. Not only a general quantitative reduction of calories should be instituted, but their quality should also be considered. […] The output of energy should be increased as far as possible by the prescription of greater muscular activity, in the form of walking and other physical exercises, with due regard to the patient’s cardiac state. (18)

5.

Continuing on page 116, Taubes writes:

By 1938, Russell Wilder, the leading expert on diabetes and obesity at the Mayo Clinic and soon to become director of the Food and Nutrition Board of the National Academy of Sciences, was writing that this German-Austrian hypothesis “deserves attentive consideration” […]

Interestingly, Wilder prefaces the above quote with “Even though one grants, as one must, that the caloric balance will determine in the end whether fat is deposited or released from storage in the body as a whole […]” (19)

Why Taubes excises this bit of text should be obvious to anyone paying attention.

6.

By 1940, the Northwestern University endocrinologist Hugo Rony, in the first academic treatise written on obesity in the United States, was asserting that the hypothesis was “more or less fully accepted” by the European authorities. Then it virtually vanished.

I think it’s important to note a few things here. First, Rony did not claim it was accepted by “the European authorities” (Taubes also makes this mistake in GCBC by stating it was accepted “in Europe”), but rather that it was accepted in Germany. Minor point, but worth mentioning because Taubes clearly expands the acceptance from one country to an entire continent to make it seem more legitimate. Second, Rony also mentions a few things immediately following the “more or less fully accepted” quote that are less than charitable to the theory. Notably on page 174,

[T]he main elements of this attractive theory remain as hypothetical as they were thirty years ago. Thus, there is as yet no direct evidence that the fat tissues of obese subjects have an increased affinity to the glucose (and fat) of the blood. […] The results of glucose and fat tolerance tests made on obese and non-obese persons do not support the assumption that ingested glucose and fat disappear from the blood of obese subjects faster land at lower thresholds than from the blood of non-obese subjects. (Chapter VI). Neither is there any material evidence to show that the fat depots of obese persons resist fat mobilization at times of caloric need for energy consumption more than the fat tissues of non-obese subjects do. On the contrary, it appears from data concerning the basal metabolism and nitrogen output in undernutrition (page 72 and 149), that the fat of the fat depots of most obese subjects is more readily available for energy consumption than that of non-obese subjects. Furthermore, we have no valid proof that glandular or nervous system disturbances, in producing generalized obesity, act primarily upon the fat tissue. (20)

Emphasis mine. In fact, the entire Rony text is really devastating to Taubes’s theory, in that it fully supports what Taubes calls the “energy-balance theory” and effectively rejects the fringe theories like those Taubes promotes.

7.

On page 228 Taubes describes a visit to Africa by Dr. Hugh Trowell:

When Trowell arrived in Kenya, he would later write, hypertension and diabetes were absent. The native population was also as thin as “ancient Egyptians,” despite consuming relatively high-fat diets and suffering no shortage of food. *

There’s also a footnote to this passage:

* During World War II, according to Trowell, the British government sent a team of nutritionists to the region to learn why local Africans recruited into the British Army could not gain sufficient weight to meet army entrance requirements. “Hundreds of x-rays,” Trowell wrote, “were taken of African intestines in an effort to solve the mystery that lay in the fact that everyone knew how to fatten a chicken for the pot, but no one knew how to make Africans . . . put on flesh and fat for battle. It remained a mystery.”

Let’s deal with the claims in the main text first. The source of these claims comes from a book titled The Truth about Fiber in your Food.(79) There is no mention of anything related to the Africans having a high fat diet. In fact, it was quite the opposite. Trowell claims the Africans were not eating enough calories:

During World War II, he was aware, a team of British medical experts had been formed and sent to Africa to advise the military authorities about army diets because Africans refused to eat the number of calories that nutritionists, and Trowell himself, advised. (79)

Emphasis mine. Related to this is Tabues footnote and the bottom of the page. What’s intriguing to me is the ellipsis that marks where Taubes omitted some words. Reprinted below is the full quote (again, emphasis mine):

“Hundreds of x-rays,” he [Trowell] recalls, “were taken of African intestines in an effort to solve the mystery that lay in the fact that everyone knew how to fatten a chicken for the pot, but no one knew how to make Africans eat their caloric requirements and put on flesh and fat for battle. It remained an unsolved mystery.”

Gary: My point was a simple one: when someone like Seth goes after my reporting, they have to get their facts straight. Credibility is everything in this business, which is why Seth was trying so hard to undermine mine. My reason for not taking him seriously is he couldn’t get his facts straight and his take on science is, well, let us just say ill-formed. It’s not his fault because no one ever taught him (it seems to be particularly absent at the U.W., where he got his masters, but that might be my own issue.)

For example, let’s talk about the kind of mistake I worry about because it's egregious and embarrassing and any journalist who makes this kind of error must, first, publicly apologize and then find a different career. In my book (and in the 2011 NYT Magazine article that preceded it) I noted that fewer than a dozen human trials were being funded “that might identify what happens when we consume sugar or high-fructose corn syrup for years, and at what level of consumption we incur a problem.” These would be trials that might vaguely teach us something researchers working in this field don’t already know. Now the NYT Magazine would have fact-checked this closely back in 2011 and I remember asking my fact-checker to do it again, so this was surprising to me that I could screw this up, let alone as egregiously as Seth suggested.

Seth goes to clinicaltrials.gov, types in “sucrose OR fructose” as search terms and comes up with 450-plus hits of which 79 might be on-going in the U.S. at the time. So now I’ve seriously done our government a disservice and readers: I said less than a dozen. Looks like I was off by almost an order of magnitude, and Seth lets me have it in full sarcasm mode.

I just re-did Seth’s exercise and you can do it, too. It will take maybe 20 minutes. I typed in “sucrose OR fructose” as search terms in clinicaltrials.gov, and then went through the first 100 of the 539 hits that came up. Maybe two of the 100 at most were relevant to the question we want answered—long term sucrose consumption and our health—and arguably only one. Virtually all the rest, as you can see if you do this yourself, were on subjects in which the word “sucrose” appears -- most often for using sucrose as a pain reliever for babies or in studies of "iron sucrose" whatever that is. Seth didn't see the need to do this kind of basic exercise. (When you're trying to publicly assassinate someone's character, apparently you don't want to waste time doing your homework).

So do this yourself: go through some subset of all the hits that come up with those search terms – you can ignore whether they're ongoing—and count up how many are relevant to sugar consumption and chronic disease risk. That’s the issue this book is about. As I said, it should take you all of 20 minutes to get a feel for whether we’re talking hundreds, many dozens, or fewer than a dozen as I wrote. Think of it as calibrating Seth’s reporting and research skills, which is what I have always had to do with the academic researchers in this nutrition business. If they can get simple things so very wrong, what’s the likelihood they get the complex things right? Particularly in a case like this when their reason for existence is to demonstrate that someone else gets the simple things wrong.

Regarding the points below, I’ll get to them shortly.

Your evocation of Yudkin, though, reminded me of an interesting aspect of all this. For starters while I think Yudkin got sugar mostly right and arguably described metabolic syndrome twenty years before Reaven did, Yudkin also made a terrible mistake, which I discussed in GCBC. He insisted that low-carbohydrate diets work merely by cutting calories and he did so on the basis of two small ill-conceived experiments. He wrote two papers on it which the establishment thinkers then quoted as evidence to support their views. I did not mention this in TCAS, because it just wasn’t relevant although maybe I should have, as they are evidence that Yudkin could get things wrong. One way or the other, Yudkin got some stuff right, for which he gets credit, and some stuff wrong which I mention when relevant. Newburgh, too, turns out to have published two papers around 1920 on the efficacy of a very low carb, high fat diet for diabetes — a ketogenic diet, in effect, aka Atkins. In that he was almost a century ahead of his time, although it went nowhere. I didn’t know this when I wrote GCBC and it’s going to complicate my next book because having spent three books blaming Newburgh for the energy balance nonsense, I’m going to have to point out that he wasn’t always wrong. In this case, dietary therapy for diabetes, he got it right. The point is sometimes folks get things wrong and sometimes they get it right and it’s the author’s judgement how to treat these and why. Einstein famously didn’t like quantum physics and it gets brought up a lot — God doesn’t play dice and all that… — but it doesn’t mean he got relativity wrong. In a book on relativity, a science historian might not mention Einstein’s feelings about quantum physics because they might not be relevant. Context is everything.

If you go back and reread my epilog of GCBC, I evoke the philosopher of science Robert Merton making this point:

In science, as Merton noted, progress is only made by first establishing whether one’s predecessors have erred or “have stopped before tracking down the implications of their results or have passed over in their work what is there to be seen by the fresh eye of another.”

That is, in effect, what I did in this book. If I’m right, no one got it 100 percent right and so often what I was doing was pointing out what others had passed over in their work or neglected to interpret fully because they were trapped in a particular perspective and I wasn’t. So Atkins, for instance, got much of this right for the time and deserves considerable credit, but he didn’t get it all and he got a lot of things wrong. Same with Yudkin. And Bauer and Pennington and all the rest. I took out what I thought was right and directed our attention to it and neglected to repeat what I thought was wrong or the particular authors being trapped in their paradigms. That is what I perceived my job to be, and I put in that Merton quote as a reminder at the end.

You can think of what I did and what Seth did as antipodal approaches. Think of it as a murder case, for instance, in which investigators have different ideas who the murderer is - say, suspect A and suspect B. Most investigators and the media think it’s A and they want to rush to judgment. But one investigator — the intrepid inspector Taubes -- thinks its B. So he goes through all the evidence and says, look, B is always at the scene of the crime and never has an alibi and there’s always at least some evidence implicating him. And the others say, yes, but so is A. The job of the investigator who thinks its B, our friend inspector Taubes, is not to rule out A, although would be nice if it could be done, but to convince his many colleagues that B is a suspect and has to be considered seriously. Maybe he should even be the prime suspect, as I’m saying in the sugar book. Seth sees it as his job to point out every time I don’t mention that A was also implicated. I disagree that it was my job. So in GCBC, I say this in the introduction:

By critically examining the research that led to the prevailing wisdom of nutrition and health, this book may appear to be one-sided, but only in that it presents a side that is not often voiced publicly. Since the 1970s, the belief that saturated fat causes heart disease and perhaps other chronic diseases has been justified by a series of expert reports – from the U.S. Department of Agriculture, the Surgeon General’s Office, the National Academy of Sciences and the Department of Health in the U.K., among others. These reports present the evidence in support of this diet-heart hypothesis and mostly omit the evidence in contradiction. This makes for a very compelling case, but it is not how science is best served. It is a technique used to its greatest advantage by trial lawyers, who assume correctly that the most persuasive case to a jury is one that presents only one side of a story. The legal system, however, assures that judge and jury hear both sides by requiring the presence of competing attorneys to present the other side.

So what Seth is often doing in his critiques is saying, look this evidence that you say implicates suspect B also implicates suspect A, and you don’t say that. My counter argument is that 1) often I do — as I’ll discuss about a few of your points below — and Seth conveniently ignores it (glass house phenomena) and 2), my job, as I acknowledge in introductions to both books, is to present the case for suspect B. As I told Seth when we first exchanged e-mails, the first draft of GCBC was 400,000 words long and unfinished. My editor, bless his heart, read the whole thing because I was wondering if we could cut it into two books. He said, no, and then we got to work shortening it. His primary advice was that I typically gave multiple perspectives for every point: first the conventional wisdom, then the reason why the conventional wisdom was wrong, then the response of the establishment scientists to the evidence suggesting the CW was wrong, and then why that response was wrong. My editor said cut out the last two levels, and you can address those in the Q&A period of the lectures you’ll be giving on this topic. And that’s what I mostly did. Many of the mistakes made — specifically with references and citations — came about because of this process of cutting the manuscript in half. Much of what Seth accuses me of leaving out are simply judgment calls. Is it up to me to present the evidence for suspect A or reiterate why suspect A is being rushed to judgment, when my job in limited space is to argue that suspect B is very much a suspect, if not the prime suspect?

In the case of the sugar book, the title and author’s note state what the book is about. The last sentence of the author’s note is this: “If this were a criminal case, The Case Against Sugar would be the argument for the prosecution.” Seth and you seem to think I should be presenting the defense case for them as well. Ironically, often I do — and I’ve been criticized for that by some of my allies in the anti-sugar crowd -- but not always.

Here goes:

Point one: This is about the 1907 BMJ report on the diabetes in the tropics issue. After the quotes that Seth thinks I should have used, Seth concludes:

If we take the whole of the text into account, we find that these Bengali gentlemen not only consume starches and pulses, but also heavy fatty foods, and they consume it all in excess. Additionally, they don’t like to exercise according to these physicians. Might these lifestyle factors play a role in diabetes? Moreover, the physicians themselves make it clear that they do not think sugar and carbs cause diabetes since diabetes can also be present in those that do not eat carbs and be absent in those that consume a lot of carbs. If these physicians thought carbs promoted the development of diabetes they would not be prescribing diets that included honey, flour, rice, sweets, and wine in the treatment diets. Why doesn’t Taubes mention this?

But Taubes does, and at length. Here’s what I wrote on page 99 in TCAS, after the quotation from the conference:

What was unclear was whether the dietary trigger of diabetes was all carbohydrates, just refined grains (white rice and white flour among them) and sugars, sugars alone, perhaps gluttony itself, or even some other factor that predisposed the well-to-do to diabetes and protected the poor. From the discussion at the British Medical Association meeting, it was apparent that poor laborers could live on carbohydrate- rich diets without getting diabetes, whereas well-to-do Indians (and even affluent Chinese and Egyptians, as was noted by physicians at the conference) who lived on carbohydrate-rich diets easily succumbed to diabetes and seemed to be doing so at ever- increasing rates. What was the difference in their diet and lifestyle? “Unless the unknown cause of diabetes is present,” wrote Allen, “a person may eat gluttonously of carbohydrate all his life and never have diabetes.” Some of the physicians at the British meeting had suggested this unknown cause was the mental stress or “nervous strain” of the life of a professional—a doctor or a lawyer— compared with the relatively simple life of a laborer (as the British physician Benjamin Ward Richardson had suggested as a cause of diabetes in his 1876 book, Diseases of Modern Life); others suggested it was the idle life led by the wealthy and their disdain of physical activity that brought on the disease. Still others thought it was gluttony, or maybe alcohol. Sugar itself, as Allen noted, was consistently raised as a possibility.

In the immortal words of our former president, “Come on, man…” Does that not make exactly the point?

Point two:

First Seth debates my use of the phrase “singularly compelling.” What I was referring to was precisely what I quoted:

“This definite incrimination of the principal carbohydrate foods,” Allen wrote, “is, therefore, free from preconceived chemical ideas, and is based, if not on pure accident, on pure clinical observation.”

I suppose Seth has an argument that I’m giving this observation too much emphasis to say “singularly compelling” but it’s only an opinion. That said, I never say Allen believed unequivocally that sugar was the cause of diabetes or that their views weren’t muddy, as you describe them. I say his textbook included a “lengthy discussion” and “he believed it had to be discussed for the obvious reason: “The consumption of sugar is undoubtedly increasing,” wrote Allen. “It is generally recognized that diabetes is increasing, and to a considerable extent, its incidence is greatest among the races and the classes of society that consume [the] most sugar.”

And then I discuss his discussion. Including this: